by Calculated Risk on 2/23/2006 07:11:00 PM

Thursday, February 23, 2006

FDIC: What the Yield Curve Does (and Doesn’t) Tell Us

FDIC economist Nathan Powell writes: What the Yield Curve Does (and Doesn’t) Tell Us

Some Excerpts:

Historically, the yield curve spread, or the difference between short-term and long-term interest rates, has had some predictive power for the performance of the U.S. economy and banking industry. In the past, a narrowing, or flattening, of the spread has tended to foretell both slower economic growth and increased pressure on bank earnings. Furthermore, the yield curve generally has inverted—a condition where short-term rates exceed long-term rates—up to two years ahead of a recession. Based on this historical context, the flattening in the yield curve since mid-2004 has been on the minds of many economists and banking analysts. Sometimes, however, the yield curve flattens or inverts for reasons that may not necessarily foreshadow slower economic growth.

The shape of the yield curve spread also has held implications for bank margins and profits. Historically, bank net interest margins have tended to decline one to two quarters after a decline in the yield curve spread. While many banks have found ways of reducing their sensitivity to changes in yield curve spreads in recent years, the largest banks have seen their margins squeezed substantially by the recent flattening in the yield curve. And although smaller banks have been less affected so far, the earnings of all lenders will likely be affected should the yield curve remain flat for several more quarters. This issue of FYI examines the historical relationships of the yield curve with economic growth and how changes in the spread have affected banks.

The Yield Curve and the U.S. Economy

A yield curve is simply a graph depicting the yields of similar debt instruments of differing maturities. There are many yield curves and many ways of measuring the difference, or spread, in short- and long-term interest rates along these curves. A common measure of this difference is the spread between the federal funds rate, which is set by the Federal Reserve and used in pricing overnight interbank loans, and the 10-year Treasury note yield, which is linked to the pricing of traditional fixed-rate mortgages. Two other common measures of the spread take the difference between 3-month and 10-year Treasury yields or the difference between 2-year and 10-year Treasury yields. Some research indicates that calculating spreads using very short-term rates, such as the federal funds rate or 3-month Treasury yield, is a more useful indicator of future economic activity than using a 2-year Treasury yield as a short-term rate.1 In keeping with this prior research, we will focus on the spread between the federal funds rate and the 10-year Treasury yield when measuring the shape of the yield curve.

Inverted Yield Curves Sometimes Precede Recessions

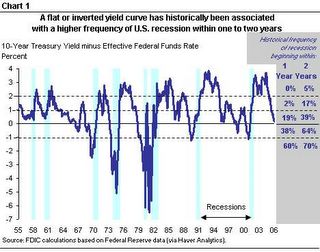

Historically, the shape of the yield curve has been a useful leading indicator of economic growth. For instance, the beginning of a recession has seldom followed a period with a steep (positively sloped) yield curve within two years (see Chart 1). In fact, during months in which the spread has measured at least 200 basis points (2 percentage points), a recession has ensued within two years only 5 percent of the time. The shape of the yield curve has also told us when recessions may be more likely. In Chart 1, we see that the yield curve has inverted significantly, or by at least 100 basis points, within two years prior to each of the past six recessions.

Click on graph for larger image.

Nathan Powell concludes:

ConclusionThe author argues that the yield curve can be flat for reasons not related to a future economic slowdown. These include low term premium, low inflation expectations, demand from foreign banks, and investment activities by pension funds and hedge funds.

History suggests that the odds of recession increase when the yield curve spread flattens or becomes inverted. But past recessions only occurred with a high frequency after the curve inverted by a significant amount for a sustained period of time. Further, the yield curve spread can invert for reasons other than the possibility of slower economic growth. We have presented some of these possible explanations, which include expectations of lower long-term inflation, a recent reduction in the term premium, strong demand for longer-term debt by foreign central banks, and investment activities by pension and hedge funds. As a result, the flat yield curve spread may not be signaling increased odds of a recession at present. By the same token, the structural forces holding long-term interest rates down may be with us for some time, even as the cyclical increase in short-term rates subsides. The presence of these structural forces suggests that a flat yield curve could persist for some time.

Similarly for banks, flat or inverted yield curves have historically been associated with narrowing NIMs and lower earnings. Many smaller banks thus far have been able to insulate themselves from changes in the yield curve spread, because they have only slowly raised the interest rates they pay on their liabilities. In contrast, the largest banks have seen their liability costs rise more rapidly, while at the same time their asset yields have lagged those for smaller banks. This situation has resulted in a classic margin squeeze for the largest banks as the yield curve has flattened. Even so, it may be just a matter of time before margins for smaller banks begin to be squeezed, especially if the flat yield curve persists. Regardless of the slope of the existing yield curve—positive, flat, or negative—bankers will benefit from strategies designed to cope with the uncertainty of changing interest rates.

None of these reasons seems compelling to me. I think it is likely that long rates are low because of foreign CB activities, but what if their economies slow? Then foreign CBs will probably lower their investment in US securities leading to higher US rates.

And the low term premiums can easily reverse. Remember Greenspan's remarks at Jackson Hole?

The lowered risk premiums--the apparent consequence of a long period of economic stability--coupled with greater productivity growth have propelled asset prices higher. ... Such an increase in market value is too often viewed by market participants as structural and permanent. ... But what they perceive as newly abundant liquidity can readily disappear. Any onset of increased investor caution elevates risk premiums and, as a consequence, lowers asset values and promotes the liquidation of the debt that supported higher prices. This is the reason that history has not dealt kindly with the aftermath of protracted periods of low risk premiums.There is much more in the FDIC article, especially concerning bank margins.