by Calculated Risk on 8/31/2018 12:16:00 PM

Friday, August 31, 2018

Labor Slack and the Participation Rate (Spreadsheet included)

Back in June, Politico obtained some responses to questions from Senators by recently confirmed Richard Clarida:

Clarida, who has been nominated for Fed vice chairman, indicated that he believes there’s more slack in the labor market. He noted that the labor force participation rate for prime-age workers, particularly men, has not gone back to pre-recession levels. “I also think this group could represent an additional margin of slack in the sense that some of them could be enticed to reenter the labor force as the demand for labor continues to strengthen,” he said.This is an interesting question.

The decline in the overall Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR) following the great recession can be divided into three parts: 1) economic weakness, 2) age related demographics, and 3) ongoing trends such as young people staying in school longer, more people working longer, more people taking time off mid-career to travel, and many other reasons.

What we'd like to know - as Clarida noted - is how much of the decline in the LFPR has been due to economic weakness. This would give an idea of how much slack is remaining in the labor market.

Removing the age related demographic changes is straightforward, but accounting for the ongoing trends is much more difficult (but important as the following graphs will show).

The first graph shows the overall participation rate (all civilians 16+ years old) and the employment population ratio.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The Labor Force Participation Rate (Blue) was unchanged in July at 62.9%. This is the percentage of the 16+ year old population in the labor force.

The overall LFPR has declined significantly since the recession, and has been mostly moving sideways recently.

The second graph shows the overall LFPR (NSA and SA) since 1987, and what we'd expect the LFPR to be - since 2007 - just based on changes in age groups.

Important Note on Data: All BLS Population data is based on Census 2014 National Population Projections Tables. These projections probably overstate the current population, especially in the prime working age groups. This analysis did not include corrections to these projections (that Census will address soon).

To adjust by age groups, the participation rate for each age and sex group was held to the 2007 levels (all data NSA). The decline in the participation rate is due to age related demographics. As large groups move from high participation ages to lower participation ages, the overall participation rate declines.

To adjust by age groups, the participation rate for each age and sex group was held to the 2007 levels (all data NSA). The decline in the participation rate is due to age related demographics. As large groups move from high participation ages to lower participation ages, the overall participation rate declines.Some analysts just looked at age related demographics to estimate the remaining slack in the labor force participation rate. However, as I've noted many times, there are long term trends that are important too.

The third graph shows the overall LFPR (NSA and SA) since 1987, and what we'd expect the LFPR to be - since 2007 - based on both changes in age AND long term trends. Note: Trends are hard, but most of the trend projections were close (some were not).

The third graph shows the overall LFPR (NSA and SA) since 1987, and what we'd expect the LFPR to be - since 2007 - based on both changes in age AND long term trends. Note: Trends are hard, but most of the trend projections were close (some were not).Using this graph, a couple of years ago when others were arguing that "most of the decline in the labor force participation rate" was due to economic weakness, I argued that most (approximately two-thirds) was related to a combination of demographics and long term trends.

The difference between using just age related demographics, and a combination of Age and Trend, is especially important for prime age workers.

The fourth graph shows the prime (25 to 54 years old) LFPR (NSA and SA) since 1987, and what we'd expect the LFPR to be just based on changes in age.

The fourth graph shows the prime (25 to 54 years old) LFPR (NSA and SA) since 1987, and what we'd expect the LFPR to be just based on changes in age.Using just age adjusted demographics, it appears there is significant labor slack remaining and someone using this graph would expect the prime LFPR to increase to from the current 82.1% to around 83% over the next few years.

However, if we look at the long trends, we wouldn't expect the prime LFPR to increase significantly.

The fifth graph shows the prime (25 to 54 years old) LFPR (NSA and SA) since 1987, and what we'd expect the LFPR to be based on both changes in age AND long term trends.

The fifth graph shows the prime (25 to 54 years old) LFPR (NSA and SA) since 1987, and what we'd expect the LFPR to be based on both changes in age AND long term trends.My estimates of the trends could be off (most groups seem close, although estimates from some groups were way off - like 55 to 59 year old women).

But this analysis suggests the Prime LFPR is close to the expected level and might only increase a few tenths of a percent from here.

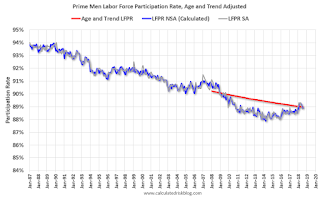

And finally, here is a look at Prime Age Men as Richard Clarida suggested.

The sixth graph shows the prime Men Only (25 to 54 years old) LFPR (NSA and SA) since 1987, and what we'd expect the LFPR to be just based on changes in age.

The sixth graph shows the prime Men Only (25 to 54 years old) LFPR (NSA and SA) since 1987, and what we'd expect the LFPR to be just based on changes in age.Using just age adjusted demographics, we'd expect the LFPR for prime age men to be increasing slightly. This is because of the older prime workers leaving the labor force and being replaced by younger workers. This suggests significant slack in the labor market for prime age men (as Clarida suggested).

However, if we account for long term trends, there might be little slack remaining for prime age men.

The seventh graph shows the prime Men Only (25 to 54 years old) LFPR (NSA and SA) since 1987, and what we'd expect the LFPR to be based on both changes in age AND long term trends.

The seventh graph shows the prime Men Only (25 to 54 years old) LFPR (NSA and SA) since 1987, and what we'd expect the LFPR to be based on both changes in age AND long term trends.Looking at this graph (and my trend estimates could be off) there is little slack for prime age men.

Of course long term trends can change. For example, the LFPR for women was increasing for decades, and peaked in the year 2000 at just over 60%, but has declined since then. If we used the period from 1950 to 2000 to predict the LFPR for women today, we would expect something close to 70%. However the LFPR for women in July was only 57.3%.

With the caveat that trends may change and are difficult to forecast, I'd conclude: 1) that long term trends are important for forecasting the LFPR, and 2) there is little slack remaining in the labor market.

Here is my spreadsheet. Please feel free to put in your own estimate of the long term trends.