by Calculated Risk on 2/21/2007 10:28:00 AM

Wednesday, February 21, 2007

MBA: Mortgage Applications Decrease

The Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) reports: Mortgage Applications Decrease  Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

The Market Composite Index, a measure of mortgage loan application volume, was 606.6, a decrease of 5.2 percent on a seasonally adjusted basis from 639.8 one week earlier. On an unadjusted basis, the Index decreased 2.9 percent compared with the previous week and was up 4.1 percent compared with the same week one year earlier.Mortgage rates were mixed:

The Refinance Index decreased 5.4 percent to 1921.1 from 2031.7 the previous week and the seasonally adjusted Purchase Index decreased 4.8 percent to 381.4 from 400.7 one week earlier.

The average contract interest rate for 30-year fixed-rate mortgages decreased to 6.19 percent from 6.24 percent ...

The average contract interest rate for one-year ARMs increased to 5.81 from 5.8 percent ...

The second graph shows the Purchase Index and the 4 and 12 week moving averages since January 2002. The four week moving average is down 1.3 percent to 398.7 from 404 for the Purchase Index.

The refinance share of mortgage activity decreased to 44.9 percent of total applications from 46.1 percent the previous week. The adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) share of activity remained unchanged at 21.2 percent of total applications from the previous week.

Tuesday, February 20, 2007

NovaStar Discussion

by Calculated Risk on 2/20/2007 05:22:00 PM

From MarketWatch:

NovaStar mulls change to REIT status NovaStar Financial said late Tuesday that it's considering whether to change its Real Estate Investment Trust status after the subprime mortgage lender reported a fourth-quarter net loss.NovaStar conference call (hat tip max):

...

Problems with mortgages originated in 2006 knocked $17.4 million, or 47 cents a share, off fourth-quarter earnings. Provisions for losses on loans NovaStar has been forced to repurchase cut $13.4 million, or 36 cents a share, off results. More provisions for losses on a package of early 2006 mortgages the company securitized cost it another $10.3 million, or 28 cents a share, NovaStar said.

...

REITs have to distribute at least 90% of their taxable income as dividends. NovaStar Chief Financial Officer Greg Metz said the company expects to recognize little, if any, taxable income in 2007 through 2011, so "management is currently evaluating whether it is in shareholders' best interest to retain the company's REIT status beyond 2007 given the asset, income and other REIT-related restrictions the company must operate within."

emphasis added

Wells Fargo: Layoffs Due to Tighter Credit Policy

by Calculated Risk on 2/20/2007 04:16:00 PM

From Charlotte Observer: Wells Fargo cuts 250 jobs in Fort Mill

The cuts are the latest fallout from problems in the business of subprime lending -- lending at high interest rates. Demand for new high-rate loans is shrinking even as defaults on existing loans are rising, leaving lenders with less revenue and more expenses.

Wells Fargo, like other large mortgage lenders, has responded to the defaults by tightening the requirements for new loans, further shrinking the volume. The Fort Mill office, which is part of the company's subprime operation, will have less work to do.

"We tightened our credit policy," Wells Fargo said in a statement. "This decision directly impacts our nonprime loan volume, which in turn impacts staffing levels in the areas devoted to managing these loans."

Tanta: Mortgage Servicing for UberNerds

by Calculated Risk on 2/20/2007 12:26:00 PM

StillLearning asked in the comments about mortgage servicing, and since y’all are nerds, not dummies, here’s my highly-selective occasionally-oversimplified summary for you that skips the boring parts like how your check gets out of the “lockbox” and that stuff. We can discuss extra-credit issues like “excess servicing” and “subservicing” and “SFAS 144 meets MSR” and “negative convexity” and other kinds of inside baseball in the comments. There is a lot that can be said about loan servicing, but let’s start with the basics:

Servicers have two major types of servicing portfolio: loans they service for themselves and loans they service for other investors. In accounting terms, the “compensation” is the same, meaning that even if you are the noteholder, you pay yourself to service the loans in the same way that an outside investor would pay you, and it shows on the books that way. The differences in compensation stem from the basic fact that one is generally more motivated to do a good job servicing (particularly collecting and efficiently liquidating REO) for one’s own investment than for someone else’s.

So major investors like the GSEs have all sorts of supplemental compensation structures in place for their servicers: everyone may start out being paid just the basic servicing fee, but if you meet the GSE goals for loss mitigation and general performance standards, you get “bonuses.” Private label security servicing agreements are huge and complex, and the terms can vary. Often the way those deals provide the “extra” incentive for the servicer to do a good job is the fact that the servicer is the issuer, and the issuer retains the residual or equity tranche of the deal—so the servicer does have skin in the game when it comes to mitigating losses.

The basic economics of servicing compensation is that the servicer gets what is called a “servicing fee” on each loan equal to a slice of the interest paid. The usual servicing fee for prime loans is .25% for fixed rate and .375% for ARMs; FHA/VA loans are .44%. What you get in subprime varies widely; generally, the worse the credit quality, the more you have to pay the servicer, because the more work the servicer will do (i.e., making collection calls to get the payment in each month). ARMs are more servicing work than FRMs because the rate and payment adjustments have to be processed, notices sent, loan balances recast, etc. Servicers generally get to keep part or all of late fees (those don’t get passed on to the investor), which can create a perverse incentive: it compensates the servicer for the additional expenses of handling a delinquent loan, but it can tempt the servicer to post payments in a tardy fashion or to not bother with collection calls until after the point where a late fee is assessed to assure the fee income. The real bottom-feeder servicers make a fortune on this kind of crap. (Hence the GSEs’ “bonus” program for loss mitigation efforts: it’s a way to “reincentivize” the process so that the servicer “wins” when a troubled loan becomes current again and those late fees go away.)

The general fact about servicing fees is that they are always paid first: technically, of course, the servicer gets the payment, so the servicer gets to take its 25 or 37.5 bps off the top before passing the rest through to the investor. (There’s also non-negligible “float” income here for the servicer, as payments get collected on and around the first of the month but the “cutoff” for passing them through to the investor generally isn’t until the 25th or so.) But it’s more than just a technical fact; it’s a risk management thing, like the airline drill where passengers are advised to adjust their own oxygen mask first before assisting their children. No investor ass will be covered unless there’s a servicer to cover it, so you pay the servicer first. On the other hand, the servicer is the very first party to incur any expense in the case of delinquency or default, and the servicer’s expenses just “rack up” until final liquidation (payoff if the loan is refinanced or the property sold voluntarily, liquidation of the REO if the loan is foreclosed). Once again, though, servicer expenses come “off the top” of the liquidation proceeds, and the investor gets what’s left over.

Hence there’s always a balancing act going on between servicer and investor: if, as an investor, you want to micromanage your servicer, to make sure that it isn’t going hog wild with expenses or dragging things out until there are no proceeds left for you, you can find yourself spending too much money “redundantly servicing” loans to have any worthwhile yield left. On the other hand, if you don’t force the servicer to get your permission to take certain steps, you won’t have any yield left because the servicer eats it in expenses or throws away the property for a sweetheart price just to get the problem off the expense-o-meter.

We were talking the other day about Wells Fargo’s servicer rating being “used” to improve the rating of co-issued securities. WF is a good example of a good, conservative servicer (at least from an investor’s perspective) who doesn’t have to be babysat or argued with all the time. You very frequently do get what you pay for in this industry, and an investor might pay WF more for servicing loans, but still come out ahead of someone using some bottom-feeder servicer whose contract looks like a deal until you find out how it is going to be managed.

In any case, the other side of “float” for the servicer is the usual requirement that the servicer advance interest (and possibly principal, although that’s less common) to the investor when it is “scheduled” to be due but wasn’t actually paid by the borrower. You’ll see, for instance, the term “scheduled/actual” used to refer to a servicing arrangement. That means that the servicer must pass through all scheduled interest each month, whether collected from the borrower or not, but only actually collected principal. Most deals these days are S/A or S/S. (A/A exists, but it’s like “with recourse,” which we talked about on a prior thread. It takes a very well-capitalized, high-risk tolerance investor to accept an A/A deal; most of the ones I see these days are old Freddie Mac MBS that are down to six loans each and just won’t die until the last payment is made.)

Having to advance scheduled interest offsets the float; it’s another way to balance the incentives. It really starts to matter when we get to this thing called “nonaccrual.” Basically, a usual servicing contract will require the servicer to advance interest until the loan is more than 90 days delinquent, after which it is placed in “nonaccrual” status, meaning it is deemed uncollectable and no more interest has to be advanced. (Note: this doesn’t mean that past-due interest is “forgiven” for the borrower; it means that the investor can no longer “count” past-due interest as noncash income, because the odds of ever getting it are getting ugly.)

Even if the servicer no longer has to keep advancing scheduled interest, though, it has to keep paying property taxes and insurance, if the borrower isn’t paying it, until the property is sold. It also has to cover the other expenses in a foreclosure (unless the contract specifies that the investor or mortgage insurer will advance for certain costs) until the final payday. In practical real-world terms (not the pretty stuff you see in contracts), when recovery values in a foreclosure are high (in an RE boom), servicers can noodle along and rack up expenses you didn’t know existed—i.e., shove as much of your “overhead” into FC expenses as you can get away with, since someone else will eventually pay the tab. That’s what we mean when we say that you used to be able to make money off a foreclosure. When the liquidation value starts to approach or drop under the loan amount, on the other hand, investors and insurers start going over those expense reports with a fine-toothed comb, and it can end up in the same kind of “war” we’re seeing with repurchases.

There are two important things to know about loan servicing income in the normal (non-delinquent) side of things. One, loan balance matters to servicers in a way it doesn’t matter to investors. If you are buying, say, a $1MM interest in a $500MM pool of loans, you get the WAC (weighted average coupon or interest rate) on your million, regardless of whether that million is made up of 20 $50,000 loans or 2 $500,000 loans. Of course, if your yield is really coming from 2 $500,000 loans, you’re at much higher risk of losing yield due to refinance or principal due to default, since one-out-of-two isn’t great odds. But that’s why you’re buying a small piece of a huge pool, so you don’t have that kind of risk (the whole-loan investor has that kind of risk).

The servicer, on the other hand, gets its 25 bps for the $50,000 loan and the $500,000 loan, while its fixed costs are the same for each loan. Not only that, the fixed costs are “front-loaded” (for performing loans, remember). The big expense is getting the loan “boarded” on the servicing system, getting the initial notices out, doing the initial escrow analysis and tax setups and so on; after that (until the annual tax bills or annual ARM adjustments come into play), a performing loan is a cheap deal: payment comes in each month, gets posted, it drives itself at this point. But this means that the $50,000 loan has to stay on your books a lot longer than the $500,000 loan does for you to get past break-even, because the servicing fee/float income is a little bit a month, not an upfront lump sum. Loan officers and brokers get paid upfront lump sums for loans, so they like big loans too. Underwriters get nervous about big loans, because with loan balance increase comes credit risk increase.

So there are competing pressures—costs, risk, efficiency—in the industry regarding loan balance. In a “normal” environment, these competing pressures (servicers want the bigger loans, investors want the smaller loans) keep risks reasonably mitigated. But next time you see some statistics showing a much lower average loan balance for subprime pools, bear in mind that this isn’t just because subprime borrowers often can’t afford to borrow more. It’s because small loans have to have large servicing fees, in order to make them worthwhile for the servicer, so they have “subprime” interest rates. FHA pays 44 bps in servicing not just because their loans don’t perform as well as Fannie/Freddie loans; they also do this so that servicers will service those smaller, therefore less profitable, loans and not cut low-to-mod home-price borrowers out of the market.

The other thing is that, in direct terms, the interest rate on the loan doesn’t matter to the servicer (loan balance being equal). If I’m servicing an 8.50% loan for you, I take .25% off the top and pass through 8.25% to you. On a 4.50% loan, I take .25% off the top and pass through 4.25% to you. The servicer gets paid first, and I get my quarter and you get the rest. Indirectly, though, the servicer’s income is rate-dependent because of refinances. High-rate loans prepay faster than low-rate loans, when prevailing market prices change and the “booms” happen, so a high-rate loan is less likely to stay on the books long enough to cover costs and start generating actual profit. When market rates go up, the investor who is getting 4.25% on loans that will not refinance is losing money, because it could buy a new loan and get 8.25%. However, the servicer’s income is best in that situation, since its profitability is time-dependent, not actual yield-dependent.

This means several things. Servicing income is “counter-cyclical,” so a bank that has both a mortgage investment portfolio and a servicing platform can make money either way, if not always at the same time. Also, servicers have a built-in incentive to keep the loan going, where the investor might like to see it foreclosed. The whole uproar over servicers doing “modifications” as if it were only a way to “hide” losses misses the point that the servicer’s financial incentive is to keep getting its quarter every month. Sure, you can originate a new loan to replace the old loan, but you have those front-loaded fixed costs that don’t go away. Finally, the name of the game in servicing is “economy of scale.” The consolidation of the servicing industry from the days of Tanta’s youth to the present has been nothing short of extraordinary. The servicing market is dominated by the 800-pound gorillas, and will stay that way unless and until market incentives change or risk concentrations get so out of hand that someone has to create some “Baby Bells” out of this.

The end of the long story is that “normal” mortgage environments have lots of opposing forces in more or less equilibrium: the originator, the investor, the servicer. When the environment is not normal, distortions come in and risk levels can appear that are not “historically” usual (and everybody acts surprised). There is going to be some major whining, moaning, and gnashing of teeth by mortgage originators, should we have a real-live credit crunch, that you won’t necessarily hear from mortgage servicers, who have been taking it the shorts all these boom-years and are about to start getting profitable, assuming that delinquent-servicing costs don’t explode on them. If they have the staff to handle the FCs and BKs and REOs, it’s gravy because the investor and insurer are going to end up covering those costs as long as they’re justifiable. If you’re an inefficient servicer whose expense reports don’t pass the investor’s smell test, you’ll lose money if the REO doesn’t sell fast enough. If you’ve been puzzled about what motivates the “nuclear waste” buyers, now you know—they aren’t looking for yield on a note, they’re looking for profit on distressed-loan servicing. The reason they’re offering such crap bids is that the REO isn’t moving fast enough, which increases their expenses and thus eats into their profits. (That and the fact that the loan documents are such a giant mess in so many of these deals that it will take the Olympic Lawyer Relay Team to sort it out.)

That said, what you want to watch if you’re looking at a servicer is the category of loans that are 90+ days delinquent but not yet REO. That may not be anyone’s largest pile of delinquent loans (out of the total of 30-60-90-120-FC-REO), but it’s the one that is the expense-hole. Anyone who is letting that bucket get bigger at a faster rate than it is racking up 60-day delinquencies has a problem. Every loan that is 90 days down this month was 60 days down last month, so out-of-proportion increases in the 90+ category means that the trouble is on the liquidation (escape) side, not just the credit deterioration (entry) side: BKs or legal-document troubles are delaying foreclosure, or nobody really wants to foreclose right now because the bids are going to suck so badly. Dragging it out, though, just makes the servicer wait that much longer to get paid and eats away at what the investor will recover. It’s expensive to carry REO and market it, but you can’t list it until you own it and you can’t sell it until you list it. There are ways to win at the servicing game, but there are also many ways to lose.

WSJ: After Subprime, Danger Lurks

by Calculated Risk on 2/20/2007 02:57:00 AM

From Justin Lahart at the WSJ: After Subprime: Lax Lending Lurks Elsewhere

Investors who dabbled in subprime mortgages have learned that risk is a four-letter word. The lesson might need to be applied elsewhere before too long.My suggestion: take a hard look at CRE and C&D. When "things get ugly", defaults in CRE and C&D really increase (see early '90s on this Fed chart for commercial real estate).

...

When housing was hot, subprime mortgages seemed like a sure thing. ... The default rate has since soared.

Could this happen to other borrowers? Mortgage lenders rely on FICO scores for conventional mortgages, too. And easy money hasn't been limited to mortgages. Yields on junk bonds -- the debt of the least creditworthy companies -- have never been as low against comparable Treasury yields as now. The same is true of emerging-market debt. Defaults on these bonds are low, as they were in subprime a few years ago. But how comforting should that be?

...

The downturn has been marked by an unexpectedly large number of "early defaults," for which borrowers stop paying shortly after getting their mortgages. [Asset-backed securities research Thomas] Zimmerman sees "soft fraud" in the mix of defaults. Someone might take out a mortgage, buy a home, avoid payments and live rent-free until the marshals come.

Nobody seemed to realize the risks inherent in extending mortgages with loose standards that left borrowers with little skin in the game. The question worth asking now: Where else has lax lending been going on?

If the answer is far and wide, things could get uglier.

Monday, February 19, 2007

Kellner: Blame it on the Weather

by Calculated Risk on 2/19/2007 11:09:00 PM

From MarketWatch: It's the weather, stupid

No, Virginia, the economy did not suddenly step into a hole in the past month. Rather, it simply got stuck in a humongous pile of snow.This article makes a good point - one month does not make a trend, especially when the weather is unusually bad (or good).

There's no getting around it: The past week's slew of economic data was far from what the pundits expected. ... On the surface these developments look ominous. ...

Before you push the panic button, let me remind you that January is a notoriously bad month on which to base conclusions regarding the state of the economy. This is because it tends to be a cold, snowy month in most parts of the country, thus curtailing a wide range of economic activity, from shopping to homebuilding.

True, government statisticians adjust for these regularly-recurring declines, but when the weather is unusually rough, these seasonal adjustments cannot fully ameliorate the effects of the weather and the reported numbers take a dive.

This is what happened in the past month. Snow measured in feet rather than inches kept people out of stores and prevented them from going to work, whether to their factories or to the jobsite.

Investment Lags

by Calculated Risk on 2/19/2007 01:10:00 PM

By how many quarters does Non-residential Investment lag Residential Investment?

There are two components of non-residential investment: 1) equipment and software, and 2) non-residential structures. The following graphs shows how the YoY change in investments, in equipment and software and structures, correlates with residential investment with lag times between zero and seven quarters. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

The highest correlation for equipment and software is a lag of 2 to 3 quarters, and for structures a lag of 4 to 5 quarters. There is a positive correlation for other periods also.

The YoY change in residential investment turned negative in Q2 2006 (quarterly residential investment turned negative in Q4 2005).

For equipment and software, investment declined in two of the last three quarters. With a lag of 3 quarters, the YoY change would turn negative in Q1 2007. Of course the lag might be longer, or YoY investment might not turn negative this time.

For non-residential structures, a lag of 5 quarters would suggest the YoY change would turn negative in Q3 2007. The quarterly change in structure investment slowed significantly in Q4 2006, but it was still positive.

Note: The correlation used data by quarter since 1960. There are 44 degrees of freedom (since some of the YoY changes are not independent). We can be 99.9% confident that residential investment and equipment and software are positively correlated, since 1960, with lags of between 1 and 4 quarters.

We can be 99% confident that the YoY change in investment in non-residential structures and residential are positively correlated with lags of between 3 and 6 quarters.

Sunday, February 18, 2007

Subprime Damage: "It is only a matter of when"

by Calculated Risk on 2/18/2007 12:39:00 PM

... the damage of the mortgage mania has been done and its effects will be felt. It is only a matter of when.From the IHT: Investors in mortgage-backed securities are failing to react to the plunge in the mortgage market. A few excerpts:

It is becoming clear, however, that subprime mortgages are not the only part of this market experiencing strain. Even paper that is in the midrange of credit quality — one step up from the bottom of the barrel — is encountering problems. That sector of the market is known as Alt-A, for alternative A-rated paper, and it is where a huge amount of growth and innovation in the mortgage world has occurred.And who are the bagholders?

[Joshua Rosner, a managing director at Graham & Fisher & Co., and Joseph Mason, associate professor of finance at Drexel University's LeBow College of Business] find that insufficient transparency in the CDO market, significant changes in asset composition, and a credit rating industry ill- equipped to assess market risk and operational weaknesses could result in a broad financial decline. That ball could start rolling as the housing industry weakens, the authors contend.

"The danger in these products is that in changing hands so many times, no one knows their true makeup, and thus who is holding the risk," Rosner said in a statement. Recent revelations of problem loans at some institutions, he added, "have finally confirmed that these risks are much more significant than the broader markets had anticipated."

Saturday, February 17, 2007

Subprime: The impact on Existing Home Sales in 2007

by Calculated Risk on 2/17/2007 02:59:00 PM

What will be the impact of tighter lending standards in the subprime mortgage market on existing home sales? First, some numbers ...

UPDATE: Here is a graph from immobilienblasen (via mish):

This graph is from Inside Mortgage Finance and shows the subprime share of the mortgage market near or over 20% for each of the last 3 years.

Original Post:

From America’s Second Housing Boom (hat tip: Blackstone):

By 2005, subprime originations had risen to $625 billion, now up to 20 percent of total originations and 7 percent of the total outstanding mortgage stock.

This is 2005 data, and other sources (and here) suggest non-prime (subprime and Alt-A) mortgage lending was about one third of all originations in 2005 and 2006.

Nonprime originations were 33% of market in 2005, up from 11% in 2003And, according to this note perhaps 25% of subprime borrowers will be unable to obtain loans in 2007:

Merrill researcher Kamal Abdullah raised the specter of a subprime "contagion" that could lead to the inability of the "bottom" 25% of all subprime borrowers to get loans.So if one fourth of potential subprime borrowers are unable to purchase homes in 2007, as compared to 2005 and 2006, then 25% of 20%, equals 5% of the total market. In 2006, there were 6.48 million existing homes sold, so 5% would be just over 300K homes.

But it's worse: The housing market is a sequence of chained reactions (just ask any agent or broker). If 300K buyers are excluded, the number of fewer houses sold in 2007, compared to 2006, is some multiple of that number. So this will probably have a significant impact on sales in 2007.

How far will sales fall?

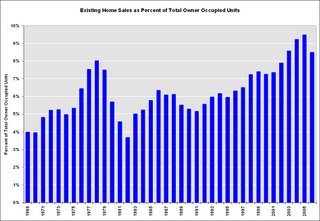

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows sales normalized by the number of owner occupied units. This shows the extraordinary level of sales for the last few years, reaching 9.5% of owner occupied units in 2005. The median level is 6.0% for the last 35 years.

Some of the sales were for investment and second homes, but normalizing by owner occupied units probably provides a good estimate of normal turnover. If sales fell back to 6% that would about 4.6 million units. If sales fell back to the level of 1998 to 2001 (7.3% of total owner occupied units sold) that would be about 5.6 million units in 2007.

Fannie Mae is projecting existing home sales will fall to 5.925 million units in '07. My guess is existing home sales will "surprise" to the downside, perhaps in the 5.6 to 5.8 million unit range.

Friday, February 16, 2007

Warehouse Lender Acting "Irrationally"

by Calculated Risk on 2/16/2007 04:23:00 PM

From MarketWatch: Merrill, J.P. Morgan pull back in credit crunch at low-end of mortgage market. This article is mostly a summary of recent events:

A credit crunch in the market for low-end mortgages has left companies specializing in these subprime loans at the mercy of big banks like Merrill Lynch & Co. and J.P. Morgan Chase.But this is interesting:

...

Warehouse lenders have started worrying about the quality of subprime loans that have been originated in recent years. Some are now asking subprime specialists for bigger haircuts, putting the originators in financial peril and forcing some into bankruptcy.

"Warehouse lenders are the lifelines for a lot of these subprime originators because they don't have the financial capacity to fund these loans by themselves," Ernie Napier, head of the specialty finance team at rating agency Standard & Poor's, said. "To the extent that these warehouse lenders go away, the whole process starts to unravel."

"We have eight different warehouse lenders; I would say the majority of them are acting very rationally," [Stuart Marvin, executive vice president, Accredited Home Lenders] said. "There is one that is acting somewhat irrationally, although I won't mention them by name. We have migrated the fundings away from that warehouse lender to one of the other seven until they begin to act more rationally again."Someone is acting "irrationally"? Maybe someone has taken some huge losses. Or maybe, in Mr. Marvin's view, the seven other warehouse lenders will start acting "irrationally" soon.

Industry publication National Mortgage News said this week that Merrill Lynch has been making margins calls. A Merrill spokesman declined to comment.