by Calculated Risk on 3/19/2007 11:54:00 AM

Monday, March 19, 2007

First American Study on Foreclosures

From the OC Register: Homeowners face foreclosure

The United States likely will see 1.1 million foreclosures during the next six to seven years on adjustable-rate mortgages issued when home prices were at or near the peak of the market, a study released today by First American Corp. of Santa Ana says.Compare this to the Center for Responsible Lending report: Losing Ground: Foreclosures in the Subprime Market and Their Cost to Homeowners.

As a result, lenders will end up losing about $112.5 billion.

But that probably won't have a significant impact on the economy or the mortgage industry since the loss equals less than 1 percent of the $12 trillion in home loans projected for the next six years, the study said.

"This is not going to break the economy," said study author Christopher Cagen, director of research and analytics at First American CoreLogic, a First American company. "It's less than the price of alcohol. It's less than the price of gasoline going up to $3.25 a gallon. ... It's part of the business cycle and it's not going to be dominant."

"... foreclosure rates will increase significantly in many markets as housing appreciation slows or reverses. As a result, we project that 2.2 million borrowers will lose their homes ...I'm trying to find the First American study.

...

We project that one out of five (19 percent) subprime mortgages originated during the past two years will end in foreclosure. This rate is nearly double the projected rate of subprime loans made in 2002, and it exceeds the worst foreclosure experience in the modern mortgage market, which occurred during the “Oil Patch” disaster of the 1980s."

Sunday, March 18, 2007

Commercial Bank Exposure to Real Estate

by Calculated Risk on 3/18/2007 04:18:00 PM

Professor Kash had an interesting post on Friday: Bad Loans, Banks, and the Coming Credit Crunch Kash is trying to look at the incipient credit crunch from the bank's perspective.

"I've been thinking about the health of the banking sector of the US economy, and pulled together a couple of charts that have gotten me thinking. And worried."Check out Kash's post and graphs.

Kash presented the loan amounts in real terms. The following graph shows the loan amounts as a percent of GDP (Q1 2007 estimated).

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows the rapid increase in real estate loans. This category includes all loans collateralized by real estate, and includes residential, commercial and real estate construction and development loans.

The banking sector is clearly exposed to real estate, although the breakdown between residential and commercial isn't available.

Note: Commercial and industry (C&I) bank borrowing has risen recently as a percent of GDP, but the level is still low compared to historical norms. However this is bank loans only, and doesn't include any bonds. I'll have more on consumer borrowing soon.

We know, from the FDIC Semiannual Report that the concentration of CRE and C&D loans has increased:

Small and mid-size institutions have been increasing their concentrations in riskier assets, such as CRE loans and construction and development (C&D) loans. This suggests that, although small and mid-size institutions have been more successful in limiting the erosion of their nominal NIMs, they have achieved this success in part by assuming higher levels of credit risk.

... continued increases in concentrations and reports of loosened underwriting standards at FDIC-insured institutions signal the potential for future credit quality deterioration. In addition, regulators have noted increasing C&D and overall CRE loanThe housing crisis is now front page news, but there is little discussion about U.S. bank exposure to CRE loans. If a CRE slump follows the residential real estate bust (the typical historical pattern), then the U.S. commercial banks might have a serious problem.

concentrations, especially at institutions with total assets between $1 billion and $10 billion.

Currently delinquency rates are very low for CRE loans. But when times are tough, CRE loans usually have the highest overall delinquency rates.

Currently delinquency rates are very low for CRE loans. But when times are tough, CRE loans usually have the highest overall delinquency rates.I understand why Kash is thinking about this issue ... and why he is worried.

Tanta on FICO "Inflation"

by Calculated Risk on 3/18/2007 02:47:00 AM

From CR: At the OC Register, Mathew Padilla interviews Glenn Stearns of Stearns Lending. Here is an excerpt:

Stearns also said there has been an inflation in credit scores, known as FICO scores. He said some consumers with a maximum of $3,000 in credit had a FICO of 700, which generally is considered a good score. Such a first-time buyer had no proven history of making a house payment, he said. In his own business, he said customers that went into default tended to have credit scores greater than 700.This makes it sound like FICO scores are undergoing a process like “grade inflation” in college. Tanta explains that the problem isn't with the FICO score itself, but that using the FICO score alone is insufficient for first time homebuyers.

“Everyone is having to rethink credit scores,” he said.

The following is from Tanta:

Some of us (OldFart Mortgage, LTD) used to require a first-time homebuyer to have a 24-month rental history, and to verify that with a direct verification from the landlord or property management company. First, we would make sure that the borrower had a history of making housing (not “house”) payments on time. Then, we would calculate the borrower’s current housing expense as a ratio to gross monthly income, and compare it to the borrower’s proposed monthly housing expense (including taxes and insurance). The result of this comparison is actually what old-timers mean by the term “payment shock.” (The term for potential future issues on an ARM was “rate shock”; the press has completely muddled the terms now so much that it’s hopeless.) Anyway, the traditional rule of thumb was that a first-time homebuyer was limited to a proposed house payment no more than 150% of the current housing (rental) payment. That extra 50% allowed owning to be more expensive than rent, but also was conservative enough to allow for things like maintenance and other expenses that renters aren’t often in the habit of paying for. If you let them double their monthly housing payments, they can get into terrible trouble the first time they have to call a plumber. The theory is that second-time homebuyers have already learned this awful lesson and so they can be allowed more “shock” (as long as they still meet the total DTI max).

In any case, this verification of the rental payment history and “payment shock” test was on top of the required minimum FICO. So those borrowers described in the article—a nice pretty 700 FICO derived from one $3000 card balance—would not get the loan if they didn’t meet the other two tests. For instance, this old rule eliminated FTBs who were going straight from mom & dad’s place (or the dormitory) to a mortgage: they were ineligible because they couldn’t show a 24-month history of being responsible for their own housing costs. Ditto for someone “renting” a condo owned by the parents but not actually paying anything near a real housing cost burden. I used to get those “kiddie condo” deals a lot when I worked for a lender with branches in a college town.

In my view, it is among the most irresponsible of the irresponsible lending we’ve seen lately that FTB rules were relaxed to allow either 1) no history of making one’s own rental payments required or 2) not counting late rental payments as a reduction to FICO (they won’t affect the FICO if the landlord doesn’t report to the credit bureau, and small-time property owners don’t) or 3) the payment shock limit was increased to 200% or more.

That said, it’s not so much that FICOs get “inflated,” it’s that their importance to the loan qualification process is inflated. For anyone who has already owned a home, the mortgage payment history is already taken into account in the FICO (because mortgage servicers report to the bureaus). But first-timers present a cautionary tale in not letting the FICO bear more weight in your decision than it should.

I’m sure that’s probably what the guy in the newspaper meant, but as usual, the newspaper only deals in sound bites, so my version is just the one that shows the work as well as the answer, as it were. There are some other issues a lot of us have with FICOs; they can in some cases “reward” heavy debt users over limited debt users. That’s why a sane underwriter (yeah, right) reads the credit report instead of just looking at the FICO. The other side of this, you see, is that the borrower with $3000 on the cards might have a FICO of 700, but the borrower with $8000 on the cards might have a FICO of 750 (because that person’s credit record is older, or has more tradelines—the $8000 is split over three cards instead of one, and the more trades you have, generally, the higher your score until you get to the point where you’re maxed out). So just having stricter FICO rules for FTBs would end up setting the very perverse incentive of encouraging them to get into a lot of consumer debt so they can prove they’re good enough to get a home. I would rather go back to the (“inefficient”) old days where we used FICOs, but only as a guideline that had to be backed up with other considerations, positive and negative. I certainly don’t want to see young borrowers locked out of mortgage credit because they don’t have enough plastic in their wallets or because they bought an old beater for cash instead of taking out a car loan or lease for something new, for the love of Peat. But I fear that’s the message some of them have gotten.

And that gets us back to my long-standing problem with subprime lending becoming predatory lending. A lot of folk end up in subprime because they don’t have access to the kind of credit that would improve their FICOs enough to get them into prime. If you come from the side of town where the available credit is mostly payday lenders or rent-to-own stores—who don’t report to the bureaus—you are not only getting screwed on whatever borrowing you’re currently doing, because the rates are just usurious, you’re also screwed because paying those cruddy rates in a timely fashion doesn’t offer the reward of a good FICO score. My solution to a lot of the predatory lending problem is to make sure that depositories are offering “entry level” credit to low-to-moderate income people, including young people. If the banks get ahold of them before the sleazy credit card mailers or the local loan sharks do, they can get some debt experience in a safer and sounder manner. But some banks seem to have taken the position that they’ll let Providian or the local loan shark take the risk on entry level borrowers, and then they’ll pick out the few survivors for their prime loans, while putting the others into those high-yield subprime loans. When we focus exclusively on borrower behavior, without looking at lender behavior, we get a skewed view of how you “create” a subprime borrower in the first place.

Saturday, March 17, 2007

Tanta: Negative Amortization for UberNerds

by Calculated Risk on 3/17/2007 06:44:00 PM

Confusion about Option ARMs and other kinds of negative amortization keep coming up in the comments. If you really want to know how this stuff works, you should know up front that it’s a long story. If you’re not up for the long story, skip to the next post. I would never dream of holding it against you; the following is hard-core UberNerdism, and there’s nothing wrong with just being a normal reader of the blog. In fact, I envy you. Someday the rest of us will get help for our UberNerdism; until then . . .

With a regularly amortizing ARM, the rate adjusts on some schedule that is laid out in the original contract (the note). Take a 5/1: the rate adjusts after five years, and then every year thereafter. But because it is a regularly amortizing ARM, the payment adjusts after the rate adjusts, so that the payment is always enough to cover the interest due plus sufficient principal to retire the debt at maturity (that's the definition of "amortization"). With this loan, there are no "payment caps." There are "rate caps." This means some limitation on how high or low the rate can go at any given adjustment, or over the life of the loan. The lack of “payment caps” means that the payment must go as high (or low) as it needs to in order to satisfy the rate increase (decrease). If there’s “rate shock” in this loan, you feel it immediately, because you immediately begin making payments at the “shocking” interest rate.

Negative amortization loans can work by calculating two "rates": the actual accrual rate (the real interest charged) and the payment rate (a kind of "artificial rate" used to set the minimum payment). The payment rate might also be an “introductory rate.” Here’s an example of a neg am variant on the old 5/1 ARM. (Important: this is just an example. There are jillions of unique neg am ARMs out there, and the Option ARM is even more complicated than the following. Do not assume that the following example is how they all work in exact terms; it’s just how they work in overall concept.)

In our example loan, the introductory accrual rate is 1.95% for three months. This means that the first three payments are based on an actual rate of 1.95%, and so for three months the loan amortizes (the payment due is equal to the payment required to satisfy all interest and a portion of principal.) Let’s assume a loan with an original balance of $90,000 used to purchase a property with a sales price of $100,000. For the first three payments, you get this:

| # | Beginning Balance | PMT Rate | Minimum PMT | Accrual Rate | Accrued Interest | Scheduled principal | Short- fall | Ending Balance | Original Prop Value | LTV |

| 1 | 90,000.00 | 1.95% | ($330.41) | 1.95% | ($146.25) | ($184.16) | 0.00 | 89,815.84 | 100.000.00 | 0.9000 |

| 2 | 89,815.84 | 1.95% | ($330.41) | 1.95% | ($145.95) | ($184.46) | 0.00 | 89,631.38 | 100,000.00 | 0.8982 |

| 3 | 89,631.38 | 1.95% | ($330.41) | 1.95% | ($145.65) | ($184.76) | 0.00 | 89,446.62 | 100.000.00 | 0.8963 |

After three months, the accrual rate changes to 6.50% for the remaining 57 months of the initial 5-year period. However, the minimum payment remains fixed for the remaining 57 months.* What this means is that the minimum payment required is calculated at a lower rate than the actual accrual, and so if the borrower makes the minimum payment, the loan negatively amortizes, meaning that the difference between interest accrued at 6.50% but paid at 1.95% is added to the loan balance. The borrower is not forced to make the minimum payment, although of course we’re seeing people take these loans precisely because they can’t afford the amortizing payment. You can see right here that the borrower already got “rate-shocked” in real terms, going from 1.95% to 6.50%. The borrower just doesn’t feel rate-shocked, because by making the minimum payment, the borrower is in essence borrowing enough money each month to subsidize the debt service.

Here’s what the loan looks like (condensed) for the remaining 57 months. I have broken out the “fully amortizing” payment at the accrual rate into its principal and interest components; the required payment from the borrower to actually amortize the loan (satisfy all interest due plus retire some principal) would be the total of the two. If the loan were an Option ARM with the choice of making an interest only payment rather than a fully-amortizing or negatively-amortizing (minimum) payment, the required IO payment would be the portion shown below as “accrued interest.” This chart shows the “shortfall” as the total difference between the amortizing payment and the minimum payment; the ending balance, however, is equal to the beginning balance less the difference between “accrued interest” and “minimum payment” (because “scheduled principal reduction” does not happen with a minimum payment). An alternative way to calculate that is to subtract the scheduled principal from the beginning balance, then add back the entire shortfall (not just the interest shortfall) to get the ending balance. (You may wish to have a drink before continuing.)

| # | Beginning Balance | PMT Rate | Minimum PMT | Accrual Rate | Accrued Interest | Scheduled principal | Short- fall | Ending Balance | Original Prop Value | LTV |

| 4 | 90,000.00 | 1.95% | ($330.41) | 6.50% | ($484.50) | ($82.41) | (236.50) | 89,600.71 | 100.000.00 | 0.8945 |

| 5 | 89,600.71 | 1.95% | ($330.41) | 6.50% | ($485.34) | ($83.07) | (238.00) | 89,755.63 | 100,000.00 | 0.8960 |

| 6 | 89,755.63 | 1.95% | ($330.41) | 6.50% | ($486.18) | ($83.74) | (239.51) | 89,911.40 | 100.000.00 | 0.8976 |

| ... | ||||||||||

| 56 | 98,673.00 | 1.95% | ($330.41) | 6.50% | ($534.48) | ($127.42) | (331.49) | 98,877.07 | 100.000.00 | 0.9867 |

| 57 | 98,877.07 | 1.95% | ($330.41) | 6.50% | ($535.58) | ($128.54) | (333.71) | 99,082.24 | 100,000.00 | 0.9888 |

| 58 | 99,082.24 | 1.95% | ($330.41) | 6.50% | ($536.70) | ($129.67) | (335.96) | 99,288.52 | 100.000.00 | 0.9908 |

| 59 | 99,288,52 | 1.95% | ($330.41) | 6.50% | ($537.81) | ($130.82) | (338.22) | 99,495.92 | 100,000.00 | 0.9929 |

| 60 | 99,495.92 | 1.95% | ($330.41) | 6.50% | ($538.94) | ($131.98) | (340.50) | 99,704.45 | 100.000.00 | 0.9950 |

You notice here that the ending balance of the loan after 60 payments is $99,704.45, or just over 110% of its original balance. This will become important below. Also notice that the LTV here is based on a constant original appraised value. You can make any changes you want to that original value and get a better or worse looking current LTV. But the contractual limitations on a neg am loan have to do with the relationship of current balance to original balance, not LTV. In the real world, of course, a borrower who is negatively amortizing at the same time that the appraised value of the property is dropping is getting much further underwater than this example indicates; I’m just trying to show effect on LTV if value stays constant.

After 60 months, the accrual rate adjusts to the formula of index plus margin, just like any other 5/1 ARM. However, the required payment after the first adjustment (at 60 months) is capped at 7.50% of the prior payment. If the adjustment to the new accrual rate would require a new payment greater than 107.5% of the old payment in order to fully amortize the loan, and the borrower makes the minimum payment instead, the loan negatively amortizes. The 7.50% payment cap is different from the rate cap. On a 5/1 ARM, the rate cap could be 5.00% at the first adjustment and 2.00% at each subsequent adjustment. What that means is that the rate will not increase more than five points at the first adjustment or more than two points at subsequent adjustments. If the initial accrual rate is 6.50%, at the first adjustment the rate will never be higher than 11.50% (6.50% plus five points). The payment cap, on the other hand, is a percent limitation, not points. In other words, to calculate the new minimum payment, you take the old payment and multiply by 1.075.

Using our example above, and assuming that the accrual rate increases only by 2.00% to 8.50%, the new fully amortizing payment is $802.85 ($706.24 interest plus $96.61 principal). However, the payment cap of 7.50% would limit the new minimum payment to $355.19 ($330.41 times 1.075%). On this example loan, that won’t actually happen, though. Keep reading; it just gets more complicated.

At each point, the amortizing payment is calculated on the actual loan balance outstanding. This is how neg am becomes turbo-charged ugly: if you make only the minimum payment each month, the difference between accrued and paid interest is added to your balance. Therefore, next month, your accrued interest is charged on a higher balance than last month—you are paying interest on interest. So neg am becomes “exponential” instead of “arithmetical.” It’s the reverse of compounding interest in a savings account.

So, in order to keep this exponential growth of the loan balance under control, the neg am ARM has “recast” mechanisms. These are separate from rate and payment caps and adjustments. One of the big problems with understanding all this is that too many people (including our fine media) use the terms “reset” and “recast” as if they were synonyms. You’ll never understand a neg am ARM if you do that. What we went through above was “resets” of the rate and payment. What we’re about to go through now is “recast.”

To understand recast, think of it as a process that is concurrent with but not on the same schedule as the reset process. Resets (adjustments to rates and therefore required and minimum payments) happen according to the pre-arranged terms laid out in the original note (such as every year after the first five years). But, contractually, the borrower is not required to negatively amortize; one can make the full payment, not just the minimum payment. (On an Option ARM, one can also make a full interest only payment; that doesn’t lower the balance, but it doesn’t increase it because all interest due is paid for the month.) One can also make occasional curtailments (lump sum payments of principal that don’t pay off the loan in full but that reduce its balance substantially). So for any given neg am loan, you can’t know ahead of time whether and at what point and how fast it will negatively amortize. By “how fast,” we are also referring to the magnitude of the interest rate adjustments. With any ARM, you cannot know in advance how much the rate might change at the first adjustment or any subsequent adjustment, because the new rate is determined by the formula margin (constant, spelled out in the note) plus index value (variable; the index chosen is in the note, but the actual value of it in the future is unknown). The higher the future accrual rate increases, the faster the loan will (potentially) negatively amortize.

So the “recast” provisions are a separate process of monitoring and forcing the restructure of the loan, over time, to make sure that any negative amortization doesn’t get too far out of hand. Recast provisions can be as complicated as resets, but here’s a common setup:

First, there is a provision to reamortize the loan every 60 months. What this means is that every five years, the servicer has to recalculate the minimum payment by ignoring those 7.50% payment caps. This may or may not produce huge payment shock to the borrower; it will depend on how significant the rate resets were in the preceding 60-month period, or, for the very first recast, how deep the discount was between the accrual rate (6.50% in our example) and the payment rate (1.95%). Remember that it is possible at any rate change date that the rate adjustment was small enough that the new required payment was less than 1.075% of the old payment. It is of course possible that it wasn’t, and this can hurt. In any case, this 60-month recast brings the minimum payment up to fully amortizing, but it doesn’t cancel out the regular rate and payment resets that can happen in the next five years as outlined above. So, with an ARM with annual accrual rate adjustments, the 60-month rolling recast keeps the loan amortizing for the following year; after that, neg am could start happening again (until the next 60-month recast). Think of it as a way of “catching the borrower up” every five years, but allowing them to start “getting behind again” eventually. So that is one reason why our example loan above is not going to get a new payment of $335.19, even though that’s what it would be just using the 7.50% increase limitation. The issue is that the first rate adjustment date happens to coincide with the first 60-month recast date. If the example loan didn’t have an initial fixed period of five years—say it was a 3/1 type structure—then the 7.50% payment cap might have come into play after 36 or 48 payments. (Have another drink; we’re not done yet.)

Second, there is a provision to force the loan to amortize whenever the balance hits 110% of the original balance. This is not “scheduled” like the 60-month rolling recast above; it is triggered only for a given loan if and when it has hit the 110% mark, and thus will not necessarily happen on a rate or payment change date; for some loans, it might never happen at all, if the borrower only occasionally makes the minimum payment, or makes a periodic curtailment that brings the balance down. If it does happen, the loan must become a fully amortizing loan—no more minimum payment allowed, all payments must be sufficient to pay all interest due and sufficient principal to amortize the loan over the remaining term. The percent of original balance limitation, in other words, marks the day that neg am is no longer an option for the borrower, and the loan has to start paying down principal from here on out—the borrower is “caught up,” and never again allowed to “get behind.” In our example above, the loan hit the 110% limit after the application of payment 57. So even though this loan was not scheduled for a rate increase or rolling recast until month 60, the servicer would have sent notice to the borrower that as of payment 58, the required payment is the fully-amortizing payment. Note that the loan remains an ARM, even though it is now no longer a neg am ARM. That means that the borrower’s payment can still increase or decrease at future rate change dates. It will simply be, from here on out, an increase or decrease from one fully-amortizing payment to a new fully-amortizing payment.

Neg am ARMs are structured such that the minimum payment will always satisfy at least some interest due. This is true because with a neg am loan, like any mortgage loan, payments are applied to interest before principal. I have noticed that this confuses a lot of people, undoubtedly because we all tend to think in terms of “regular” amortization, which assumes that some portion of a loan payment always goes to principal, and so people imagine that the “principal portion” of the scheduled payment could be larger than the minimum payment, which would result in no cash interest paid in a month. That cannot, however, happen. It doesn’t matter what the “scheduled principal” part of a payment might be; if the borrower’s minimum payment isn’t enough to satisfy both scheduled principal and accrued interest, the payment is applied to the interest, the unpaid interest amount is added to the balance, and no “scheduled” principal reduction occurs. (Compare that to an interest only loan, where the full interest amount is paid by the borrower in cash, but no principal, so the loan balance neither increases nor decreases.) To a borrower in hock, that’s probably a distinction without a difference, but for accounting and regulatory purposes, it’s important (see below under “noncash income” to the lender).

Has your head exploded yet?

But that’s the real point, isn’t it? If your head just exploded, and you’re the kind of person who usually reads CR, just imagine what the kind of person who doesn’t usually read CR makes of all this during some ten-minute spiel by some loan officer. We already know that there are lots of loan officers and brokers who don’t understand how these loans work; remember Babs the Wonder Broker? (One of MaxedOutMama’s finds: someone who is apparently a mortgage Account Executive who was convinced that neg am loans do not charge interest on interest. The only way that could happen is if the required payment each month were calculated only on the original balance, not the original balance plus prior shortfalls. That would, if you did it that way, leave a portion of the total loan balance that isn’t accruing interest. Of course, even if you did that during the neg am period of the loan, once you got to the 60-month recast or the 110% balance cap, you would use the total balance to recalculate the payment, and so from that point forward you would be charging interest on the capitalized interest. That’s not how these loans actually work, but the point is that even if they did work that way you couldn’t consider the capitalized balance to be “free money,” just slightly cheaper money.) So imagine some poor consumer getting “the explanation” from a loan officer who doesn’t understand how neg am works. You’d think that most adults, generally, would be suspicious if they were told by some joker on the internet (say) that banks will actually lend you money without charging interest on it. But if a broker tells you that? They must know, right?

A few more points: the issue of lenders counting negative amortization as interest income keeps coming up in the comments. I hope this example above shows why they do that: it is, actually, interest earned by the lender. It’s just interest that has not yet been paid by the borrower, which makes it “noncash” interest income. It is therefore only as “good as” the collectability of the loan as a whole. Some of us believe that as a loan negatively amortizes, its “collectability as a whole,” as a matter of probability, goes down. Some of us further believe that there are lenders out there who don’t seem to agree, and who therefore under-reserve for these loans (that is, they consider the $99,000 balance just as collectable as the original $90,000 balance, without taking into account that the more the borrower owes, the higher marginal odds of default are, and that a borrower who is making minimum payments might be doing so because the full payment is simply unaffordable).

Also, this discussion I hope makes clear that the “rate shock” issues on neg am ARMs are different from the same issue on a fully-amortizing ARM. As I said earlier, neg am ARMs are by definition a way to “smooth out” rate changes by keeping them from “shocking” the payment. Certainly, not every neg am ARM out there has a five-year initial fixed period, as my example does, or such a deep “teaser” (1.95% vs. 6.50%). Any loan with more potential rate movement in the early years of the loan can negatively amortize faster or slower than my example. We simply need to bear in mind that what is in store for a lot of these loans is the recast shock, and that that shock doesn’t necessarily happen on a scheduled rate change date. The real bad news, friends, is that these things can start blowing up more or less any time, given enough early negative amortization to start kicking in the balance caps. And yes, there are loans out there with 115% caps rather than 110% caps. So it’s incredibly difficult to project out “shocks” on these loans considered as a total portfolio, because they’re not really a homogeneous portfolio when it comes down to details like initial fixed period, depth of initial discount, rate caps, balance caps, etc. Even if they were, one would have to keep modeling “recast shock” predictions based on the actual amount of negative amortization going on, since neg am is a function of what the borrower decides to pay each month. Some of us (OK, me) are worried that the “models” aren’t being “updated” to reflect the actual amount of neg am piling up out there, or that if they are, the lenders aren’t sharing that information with the rest of us.

Last, there’s this question just raised in the comments about why or whether a lender wouldn’t just refinance these neg am borrowers into a new loan, to start the teaser rate thing all over again. Well, they could and they did when house prices were busy rising. The reason it’s a problem now is that the loan originated at a 90% LTV may now have a 99% LTV. To refinance that borrower into another neg am loan is to risk the LTV becoming 109%. I suggested at one point a while ago that a good way to think of a neg am ARM is this: a borrower makes a down payment (neg ams are usually limited to no more than 90% LTV), and then borrows it back, a little bit a month, to subsidize the monthly payment. It’s a mini monthly cash out. That can continue only as long as there is down payment to keep putting down and then slowly borrowing back, and those who refinanced a balance-capped Option ARM to a new Option ARM in the height of the boom were doing so by using that vapor-equity as the new down payment. Once that’s off the table, there’s nowhere to go with these loans except eventual amortization.

Tanta

*In this example, the initial minimum payment is simply fixed for five years. It isn’t actually recalculated every month at 1.95% instead of 6.50%. If it were, the minimum payment would increase slightly every month, because it would be calculated on a slightly higher balance every month (as the actual accrual payment is). I did it this way because many neg am loans work with this “fixed payment” thing. That’s how borrowers get confused into thinking the 1.95% is a fixed rate (when it’s really just a fixed payment “rate”). You could structure the loan such that the minimum payment is actually calculated each month at 1.95%; that would slow the negative amortization slightly by increasing the minimum payment slightly.

NY Times: Mortgage Trouble Clouds Homeownership Dream

by Calculated Risk on 3/17/2007 01:04:00 PM

From Eduardo Porter and Vikas Bajaj at the NY Times: Mortgage Trouble Clouds Homeownership Dream

Friday, March 16, 2007

Roach: The Great Unraveling

by Calculated Risk on 3/16/2007 09:52:00 PM

"Sub-prime is today’s dot-com – the pin that pricks a much larger bubble."Stephen Roach writes: The Great Unraveling

Stephen S. Roach, Managing Director and Chief Economist of Morgan Stanley, Mar 16, 2007

Sub-prime is today’s dot-com – the pin that pricks a much larger bubble. Seven years ago, the optimists argued that equities as a broad asset class were in reasonably good shape – that any excesses were concentrated in about 350 of the so-called Internet pure-plays that collectively accounted for only about 6% of the total capitalization of the US equity market at year-end 1999. That view turned out to be dead wrong.

...

This time, it’s the US housing bubble that has burst, and the immediate repercussions have been concentrated in a relatively small segment of that market – sub-prime mortgage debt, which makes up around 10% of total securitized home debt outstanding. As was the case seven years ago, I suspect that a powerful dynamic has now been set in motion by a small mispriced portion of a major asset class that will have surprisingly broad macro consequences for the US economy as a whole.

Too much attention is being focused on the narrow story ... To me, the real debate is about “spillovers” – whether the housing downturn will spread to the rest of the economy.

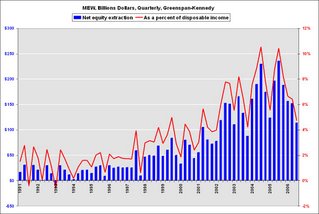

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This is a graph of the Greenspan-Kennedy MEW results through Q3

... the US economy is now flirting with ... sub-2% GDP trajectory – while consumer demand remains brisk, a pullback in personal consumption could well be the proverbial straw that breaks this camel’s back. The case for a consumer spillover is compelling, in my view. ... the asset-dependent mindset of the American consumer, debt and debt service obligations have surged to all-time highs ... Equity extraction from rapidly rising residential property values has squared this circle – more than tripling as a share of disposable personal income from 2.5% in 2002 to 8.5% at its peak in 2005. The bursting of the housing bubble has all but eliminated that important prop to US consumer demand. The equity-extraction effect is now going the other way ... that puts the income-short, saving-short, overly-indebted American consumer now very much at risk – bringing into play the biggest spillover of them all for an asset-dependent US economy. February’s surprisingly weak retail sales report – notwithstanding ever-present weather-related distortions – may well be a hint of what lies ahead.

Retail Sales and Q1 GDP

by Calculated Risk on 3/16/2007 04:40:00 PM

Update: for a review of inflation, see Macroblog: The Inflation Report: Just Not Getting Better

With the release of the inflation report this morning, we can start to estimate the real growth of consumer spending on goods (durable and nondurable) in Q1, and the contribution of retail spending to Q1 real GDP growth. This estimate is based on data for the first two months of the quarter, and could change significantly with the March data. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

This first graph shows the YoY change in nominal retail sales (from the Census Bureau) vs. the change in nominal personal consumption spending on goods (from the BEA).

The two series track very well, especially over the last ten years. This shouldn't be a big surprise since the BEA has started using the Census Bureau data to estimate spending on goods. (See Note 6: Key source data and assumptions for "advance" estimates - excel file)

Note that Q1 2007 was based on the first two months of the quarter. The second graph shows the YoY change in real retail sales (using CPI to adjust). This clearly shows the slowdown in retail spending (in real terms).

The second graph shows the YoY change in real retail sales (using CPI to adjust). This clearly shows the slowdown in retail spending (in real terms).

Now something unusual happened in Q4 2006 (and it was not widely reported). The increase in real PCE was greater than the increase in nominal PCE for the first time in about 50 years (as predicted here). This simply means that PCE prices declined in Q4.

So even though nominal spending on goods declined in Q4, the BEA reported that real spending on durable goods increased 4.4% annualized, and nondurable goods spending increased 6.0% annualized. This contributed 1.54% to Q4 GDP (out of 2.2% real annual growth). Because of the unusual decline in prices, this adjustment will probably not be repeated in Q1 2007.

Right now it looks like nominal consumer spending on goods will increase about 4% (annualized) in Q1, or about 1.0% to 1.5% (annualized) in real terms. This means consumer spending on goods will probably only contribute 0.4% or less to GDP in Q1. Those looking for 2.0% or higher GDP in Q1 will probably have to look elsewhere (or hope for a blowout March). Of course this doesn't include spending on services - about 60% of all personal consumption expenditures.

DataQuick: California House Sales Decline in February

by Calculated Risk on 3/16/2007 12:28:00 PM

DataQuick reports: California February 2007 Home Sales

A total of 31,228 new and resale houses and condos were sold statewide last month. That's down 3.7 percent from 32,425 in January, and down 21.3 percent from 39,676 in February 2006. A sales decline between January and February is not unusual. The year-over-year sales decline peaked last September at 34.5 percent.

Last month's sales made for the slowest February since 1997, when 28,710 homes sold. February sales from 1988 to 2007 range from 22,262 in 1995 to 48,409 in 2004. The average is 33,282.

The median price paid for a home last month was $472,000. That was up 2.2 percent from $462,000 in January and up 3.4 percent from $456,500 for February a year ago. The median peaked at $480,000 last June.

LA Times: A town right on the default line

by Calculated Risk on 3/16/2007 09:15:00 AM

David Streitfeld writes in the LA Times: A town right on the default line

In California, Perris is at the epicenter of mortgage problems. From November to January, 177 homes in Perris' central ZIP Code have received notices of default, the first step toward foreclosure.

That's about 1 of 53 houses ... The neighboring towns of Lake Elsinore and Moreno Valley came in second and third.

A few doors away from De Leon's house sits a second empty property foreclosed on by its lender. "A divorce," he explains. "The husband couldn't afford it alone. He was paying $2,500 a month. Ridiculous."

A few blocks away is a third foreclosure, this one only a frame skeleton abandoned by its builder. A young woman who answers the bell at a fourth house .... She pays rent to someone who pays the owner, she says; please go away.

...

There are other signs of distress. De Leon's development, called the Villages of Avalon, has an unusual number of homes for sale, considering it's so new that the Google Earth satellite scan still shows much of it as dirt.

At the top of his street, next to the charred shell of a house that mysteriously burned a few months ago, is a house for sale. The house immediately next door is on the market too. A few doors away from De Leon's home in the other direction is a third house looking for a buyer. Some owners are trying to rent their places out, advertising with little signs on the front lawn.

"Biggest Foreclosure Bloodbath Ever"

by Calculated Risk on 3/16/2007 02:56:00 AM

From Reuters: Mortgage Meltdown Pulls in More Than Those on Edge

[Lori Gay, president and chief executive of Los Angeles Neighborhood Housing Services] said she has begun meeting with lenders, at their request, to try to stave off what could be "the biggest foreclosure bloodbath that we've ever had."And on commercial real estate, from the WSJ: Subprime Troubles Bite Into Office-Space Sector

"We are seeing every age group, every single income level now, people with similar problems, and I haven't seen that in my career," she added.

Fallout from the imploding subprime-mortgage market is spreading to regions of the country where the once-torrid mortgage business generated jobs and filled office buildings.

No place is this more apparent than Orange County, Calif., where mortgage lenders including New Century Financial Corp. and Ameriquest Mortgage Co., a unit of ACC Capital Holdings Corp., have laid off workers, and landlords are bracing for a dive in what was previously one of the nation's strongest office markets. Employment in Orange County's mortgage-lending and consumer-finance sector has fallen 6.4% to 51,200 in the fourth quarter of 2006, from a peak of 54,600 in the fourth quarter of 2005, according to the Labor Department.

Last 10 Posts

In Memoriam: Doris "Tanta" Dungey

Archive

Econbrowser

Pettis: China Financial Markets

NY Times Upshot

The Big Picture

| Privacy Policy |

| Copyright © 2007 - 2025 CR4RE LLC |

| Excerpts NOT allowed on x.com |