by Calculated Risk on 6/29/2007 10:36:00 AM

Friday, June 29, 2007

May Construction Spending, Part I

From the Census Bureau: February 2007 Construction Spending at $1,170.8 Billion Annual Rate

The U.S. Census Bureau of the Department of Commerce announced today that construction spending during May 2007 was estimated at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $1,176.6 billion, 0.9 percent above the revised April estimate of $1,166.0 billion.

...

[Private] Residential construction was at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $549.0 billion in May, 0.8 percent below the revised April estimate of $553.6 billion.

[Private] Nonresidential construction was at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $343.1 billion in May, 2.7 percent above the revised April estimate of $334.1 billion.

Click on graph for larger image.

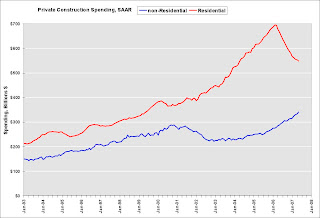

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows private construction spending for residential and non-residential (SAAR in Billions). While private residential spending has declined significantly, spending for private non-residential construction has been strong.

The second graph shows the YoY change for both categories of private construction spending.

The normal historical pattern is for non-residential construction spending to follow residential construction spending. However, because of the large slump in non-residential construction following the stock market "bust", it is possible there is more pent up demand than usual - and that the non-residential boom will continue for a longer period than normal.

The normal historical pattern is for non-residential construction spending to follow residential construction spending. However, because of the large slump in non-residential construction following the stock market "bust", it is possible there is more pent up demand than usual - and that the non-residential boom will continue for a longer period than normal.This will probably be one of the keys for the economy going forward: Will nonresidential construction spending follow residential "off the cliff" (the normal historical pattern)? Or will nonresidential spending stay strong. I'll have some comments on this question later today.

Bloomberg's Numbers

by Anonymous on 6/29/2007 08:50:00 AM

Hat tip to Ministry of Truth for bringing up this startling Bloomberg article, "S&P, Moody's Hide Rising Risk on $200 Billion of Mortgage Bonds." (How much did Fitch pay to get out of the headline?) As our fine commenters have noted, that's an amazingly bearish headline for Bloomberg. It's also a startlingly bald accusation: there's a line between asserting that the rating agencies are not downgrading bonds as fast as some observers think they should, and asserting that they are "hiding rising risk," without the usual "may be" weasel. Bloomberg just stomped right over that line, which suggests to me that tempers have become a bit short:

Standard & Poor's, Moody's Investors Service and Fitch Ratings are masking burgeoning losses in the market for subprime mortgage bonds by failing to cut the credit ratings on about $200 billion of securities backed by home loans.

"Are masking burgeoning losses"? That's even worse than "hiding rising risk." One rather hopes that Bloomberg has its numbers right.

This particular blogger is not sure she understand's Bloomberg's numbers. We get, in order:

- "$200 billion of securities backed by home loans" should have their ratings cut.

- "Almost 65 percent of the bonds in indexes that track subprime mortgage debt don't meet the ratings criteria in place when they were sold"

- "the $800 billion market for securities backed by subprime mortgages"

- "$1 trillion of collateralized debt obligations, the fastest growing part of the financial markets"

- "estimates that collateralized debt obligations . . . will lose $125 billion"

- "25 percent of the face value of CDOs is in jeopardy, or $250 billion"

- "asset-backed bonds, securities that use consumer, commercial and other loans and receivables as collateral . . . which includes mortgage securities, has doubled to about $10 trillion"

- "the $6.65 trillion in outstanding mortgage-backed debt"

- "Investors snapped up $500 million of the securities [CDOs] globally last year"

- "subprime-related debt made up about 45 percent of the collateral backing the $375 billion of CDOs sold in the U.S. in 2006"

- "Of the 300 bonds in ABX indexes, the benchmarks for the subprime mortgage debt market, 190 fail to meet the credit support standard . . . Most of those, representing about $200 billion, are rated below AAA"

OK. So we know right off the bat that item 9 has to be off by an order of magnitude if item 10 is true. If the true size of "the market" of subprime-backed mortgage bonds is $800B, that makes it 80% of the size of the CDO market, 12% of the size of the total MBS market, and 8% of the size of the total ABS market.

If $375B of CDOs were sold in 2006 in the U.S. and 45% of that involved "subprime-related debt," and we assume just for fun that "subprime-related debt" means subprime-backed MBS and that CDOs invest mostly in subordinate tranches (because we aren't sure otherwise where they get enough high-yield to make their numbers work), that suggests that there were at least $169B of low-rated tranches of subprime securitizations available to resecuritize into a CDO last year. That would be just over 20% of this "total market" of $800B. That would imply a pretty thick layer of subordination. I'm thinking that either those CDOs are buying higher-rated paper than we've been led to believe, or else, possibly, "subprime-related debt" includes things like credit default swaps on subprime paper, which implies that brains will explode before we'll be able to line up bond balances on one hand and the notional value of CDO holdings on the other.

Whatever. My brain exploded a good 20 minutes ago. Does anyone else want to take a stab at estimating the potential principal losses that exceed the current estimated principal losses on $200B in subprime ABS, so that we have some idea of how many dollars of losses the rating agencies are "hiding"?

Thursday, June 28, 2007

American Home Mortgage Pulls 2007 Guidance

by Calculated Risk on 6/28/2007 05:27:00 PM

From Reuters: American Home Mortgage pulls outlook on credit losses

American Home Mortgage Investment Corp. on Thursday withdrew its 2007 earnings forecast, and will likely suffer a surprise second-quarter loss as it takes "substantial" charges for credit-related losses.Another "surprise".

Countrywide Subprime Second-Lien ABS Downgraded

by Anonymous on 6/28/2007 05:02:00 PM

And it's only Thursday.

28 Jun 2007 3:08 PM (EDT)

Fitch Ratings-New York-28 June 2007: Fitch Ratings has taken the following actions on classes from Countrywide Asset-Backed Securitizations (CWABS) series 2006-SPS1:

--Class A rated 'AAA', placed on Rating Watch Negative;

--Class M-1 rated at 'AA+', placed on Rating Watch Negative;

--Class M-2 rated at 'AA+', placed on Rating Watch Negative;

--Class M-3 rated at 'AA+', placed on Rating Watch Negative;

--Class M-4 rated at 'AA', placed on Rating Watch Negative;

--Class M-5 rated at 'AA-', placed on Rating Watch Negative;

--Class M-6 downgraded to 'BBB-' from 'A', remains on Rating Watch Negative;

--Class M-7 downgraded to 'BB+' from 'A-', remains on Rating Watch Negative;

--Class M-8 downgraded to 'C' from 'BB+' and assigned a Distressed Recovery (DR) Rating of 'DR6';

--Class M-9 downgraded to 'C' from 'BB' and assigned a Distressed Recovery (DR) Rating of 'DR6';

--Class B downgraded to 'C' from 'BB-' and assigned a Distressed Recovery (DR) Rating of 'DR6'.

The above trust consists entirely of second liens extended to sub-prime borrowers on one- to four-family residential properties and certain other property and assets. CWABS purchased the mortgage loans from CHL and deposited the loans in the trust, which issued the certificates, representing undivided beneficial ownership in the trust.

The negative ratings actions of all classes in the trust reflect the deterioration in the relationship of credit enhancement (CE) to future loss expectations and affect $189.6 million in outstanding certificates.

The impact of the slowdown in the housing market has been particularly evident in highly leveraged subprime borrowers, and delinquency and losses to date for series 2006-SPS1 have been significantly higher than initially expected. After 12 months of seasoning, losses to date as a percentage of the original pool balance are 9.86%. Approximately 14% of the outstanding pool balance is delinquent. Due to the high percentage of losses to date, the cumulative loss trigger will likely fail for the life of the transaction. The failed trigger will generally maintain a sequential allocation of principal with the exception of principal cashflow from the subsequent recoveries of charged-off loans, which may be allocated to subordinate bonds. Fitch expects the amount of principal cashflow from subsequent recoveries to be limited.

While the subordinate classes are expected to incur principal writedowns - as reflected by their distressed ratings - the failed triggers and sequential principal allocation should help mitigate some of the risk of the weak collateral performance for the senior classes. Fitch will closely monitor the delinquency trends and roll rates in the coming months to assess the credit risk of the mezzanine and senior classes.

It Depends On How You Define "Unlucky"

by Anonymous on 6/28/2007 01:35:00 PM

June 28 (Bloomberg) -- Carlyle Group, the buyout firm run by David Rubenstein, postponed a planned $415 million initial public offering of a fund that invests in bonds backed by mortgages after a slump in the U.S. subprime market.

Carlyle is preparing a revised timetable for the sale, it said in a statement today. The Washington-based firm planned to use most of the money from the IPO to buy AAA-rated residential mortgage-backed securities. The fund also targeted loans, high- yield bonds, and collateralized debt obligations. . . .

"Carlyle's fund looked very similar to the Bear Stearns hedge fund," said Toby Nangle, who helps manage $45 billion in assets at Baring Investment Services in London. "They were unlucky with the timing."

I'd say if you're a retail investor you just dodged a bullet. I don't know that I'd call that "unlucky."

Subprime and CDOs II

by Anonymous on 6/28/2007 12:00:00 PM

This is one weird New York Times article on the Bear Hedge Horror of 2007. I'll let you all work out the blog-movie review angle.

When I came across this paragraph, I thought, aha! Exactly what I've been saying all along:

Mr. Cioffi, a longtime bond salesman who had been trading Bear Stearns’s own money for about six months, was brought over to start a hedge fund, the High-Grade Structured Credit Fund. It would invest in bonds and securities backed by subprime mortgages. While some of the mortgage-related securities were easily valued and traded, others, like collateralized debt obligations, or C.D.O.’s, do not trade frequently and can be very difficult to value.

But then I got to this part:

The approach was so successful that the company started a sister fund last summer, the High-Grade Structured Credit Enhanced Leverage Fund, that would use even more leverage.

The timing of that fund, however, could not have been worse; the cooling housing market began to reveal the lax lending standards used by subprime lenders. Last fall, delinquencies and defaults began rising, making the environment for trading and valuing the esoteric securities that are related to those loans much more difficult.

So are the mortgage-related securities the "easily valued and traded ones" or the "esoteric" ones? If the second hedge fund was started right at the time when subprime mortgage investing started to look iffy, how did it get "more difficult" to value the securities? Last fall the deterioration of the housing market and "exotic" mortgage loans was so secret we were having televised hearings on the subject by Congress. Some secret. How, exactly, does that make these puppies "difficult to value"?

(hat tip Walt!)

Subprime and CDOs: Illiquifying the Liquified

by Anonymous on 6/28/2007 10:17:00 AM

Naked Capitalism has another great post up on the Sturm und Drang in the CDO market. It doesn't exactly answer the question that has been nagging at me, namely, to what extent this "CDO valuation" crisis is truly a "direct" consequence of subprime mortgage-backed securities melting down, or whether the latter is just one of a cluster of debt-binge problems that is being amplified by Wall Street's crazy leverage schemes, one that is "easy" for the mainstream press to see and politically palatable for everyone to "blame." Save for the potentially compensatory stories of predatory lending and steering of prime or near-prime borrowers to subprime, which erupt from time to time but never become the main story, the narratives in play today are that subprime borrowers are fraudsters and deadbeats, as are subprime lenders, and this makes the two fine candidates for scapegoating.

What makes me think there might be some scapegoating going on? I'm not claiming that there are no troubles in Subprime City, of course. I am simply having a hard time reconciling the claim that there is a simple and uncomplicated relationship between these hedge funds' CDO asset valuation meltdowns, on the one hand, and deterioration in subprime mortgage performance on the other, when at the very same time this claim is made, we are informed that CDO portfolios are opaque, no one knows what's in them, and what we do know suggests that subprime ABS tranches cannot possibly be the largest share of their holdings:

And there are a few other barriers: you can't get the deal documents. No kidding. The Fed can't even get them because it isn't a "qualified investor." (Should the Fed start a hedge fund so it can study this problem?). From "Where Did the Risk Go? How Misapplied Bond Ratings Cause Mortgage Backed Securities and Collateralized Debt Obligation Market Disruptions," by Joshua Rosner and Joseph Mason (pages 83-4):At present, even financial regulators are hampered by the opacity of over-the-counter CDO and MBS markets, where only “qualified investors” may peruse the deal documents and performance reports. Currently none of the bank regulatory agencies (OCC, Federal Reserve, or FDIC) are deemed “qualified investors.” Even after that designation, however, those regulators must receive permission from each issuer to view their deal performance data and prospectus in order to monitor the sector.

So if regulators can't get the description of the securities, market participants certainly won't. So what good is a price if you aren't really certain what is being traded?

In addition, the discussion in the FT article presupposes the CDOs are passive CDOs, meaning the assets are assembled and the CDO is structured before it is sold to investors. Yet many CDOs are "active" or "managed" CDOs, meaning blind pools. Blind pools that are tranched, often with leverage and often buying other CDOs or "CDO squared" (CDOs of CDOs). That means the investors pony up money before the fund (it is like a convoluted mutual fund) is formed, and the managed gets to trade it over its three to five year life. No CDO manager is going to disclose his holdings (it would put him at a competitive disadvantage) but how can you value it otherwise?

So how do we know these things are chock-full-o'-subprime paper? Well, Yves gives us this, from the Financial Times:

What makes the CDO sector unusual is that it has exploded at such a breakneck pace with bankers packaging bonds, loans and other debts into ever more complex structures. Last year alone, about $1,000bn (£500bn, €745bn) in cash and derivatives CDOs was issued in Europe and the US, according to data from the Bank for International Settlements. More than one-third was composed of asset-backed securities, often including low-grade mortgages.

Let us first note that the term "asset-backed security" or ABS denotes a quite diverse set of instruments; "ABS" is not a synonym for "MBS." ABS issues can be and are backed by commercial loans, student loans, credit cards, auto loans, insurance premiums, aircraft leases, and probably a few dozen other asset types. When an ABS is backed by mortgages, it can, in fact, be backed by "high-grade" mortgages. (Remember the tranche versus pool problem: you can have a low-rated security tranche that is backed by a pool of very high-rated mortgages; the rating on the tranche is due to its subordination in payment priority within the security, not the quality of the collateral, since it's backed by the same collateral as the high-rated tranches.) So BIS tells us that "often" there are low-grade mortgage securities in the one-third of CDO collateral that is ABS. If you wish to claim without reservation that subprime mortgages are driving this dog cart, you're braver than I am. We just got told that not even the regulators get to see the prospectuses.

Of course the fearless reporters of the New York Times and its friends are getting on- or off-the record quotes from industry insiders claiming or implying that the CDOs and hedge funds under pressure right now are the ones heavily invested in subprime. I am only observing that not every industry quote-bot knows what it is talking about and it is quite possible that some participants have an interest in exaggerating the "subprime" part.

The curious part of it all, for me, is this question of "liquidity." Or, more properly, "illiquidity":

As this explosion has occurred, some corners of this universe have already become relatively widely traded and transparent. Every day in the London and New York markets, for example, billions of dollars worth of deals are struck involving indices of derivatives on well-known corporate bonds – making it easy to obtain prices.

However, many other such products are created by bankers directly with their clients and then simply left to sit on the books of an investor. Since such instruments typically last three to five years – and the CDO boom is so recent – many have not come to the end of their life. Nor have they been traded. Christopher Whalen of Institutional Risk Analytics, a consultancy, says: “The lack of a publicly quoted market for CDOs and like assets is exacerbating the liquidity problems for these assets beyond the underlying economics, for example, in subprime real estate.”

As Yves notes, it sounds as if Mr. Whalen is suggesting that the illiquidity of CDOs is exacerbating the illiquidity of CDOs (maybe that's the "squared" part?). But you can see why some mere mortgage punk like me gets puzzled here: was there any asset created in the last five years or so that was more liquid than mortgages? Anyone remember that part about how the investment community was beating our doors down and in fact buying up us mortgage originators as a package in unquenchable thirst for product? How liquid can you get? It wasn't quite as bad as the day-trading thing--you probably didn't get subprime whole loan bid color from cab drivers--but I'm having a hard time remembering the secretive part of the whole thing.

I can't be the only one who suspects that "illiquidity" is in some quarters the new term for "I don't like the bid." Remember all the uproar in March and April about the deterioriation of the whole-loan market for Alt-A and subprime? I can say from personal experience that nobody likes being offered par when your profitability requires you to get bids of 102.50, but that doesn't make the market "illiquid." It does suggest to me that someone has some explaining to do, not about subprime mortgages, but about these CDOs. How did we get "illiquid" securities backed by "liquid" assets? That's some impressive financial magic.

Ponder this, as well:

Some bankers and policymakers argue that this is simply a teething problem that will fade as structured finance becomes more mature. History suggests that most opaque, illiquid markets eventually become more transparent when they grow large enough – and behind the scenes, the Bear Stearns hedge fund problems are prompting bankers and investment managers to re-examine their valuation techniques. . . .

I am not a historian of financial markets, so perhaps it is true that the Whigs always win in this regard. But I would be inclined to think that perhaps it is true that in some cases "opaque, illiquid markets" become large enough to implode spectacularly before they ever get around to becoming "transparent." In fact, I wonder if in certain cases "opacity" is a feature, not a bug.

I do know enough of the history of the mortgage market to be willing to claim that it was, once upon a time, an opaque and illiquid market that did indeed become both very large and highly transparent for quite a while there. You can get an amazing amount of information about one of those nice low-yield boring vanilla GSE MBS, you know, not to mention a price right off the old Bloomberg terminal. Now, you might want to say that in the last few years somehow that famous liquidity and transparency of the residential mortgage market has largely evaporated on us, right at the time that tons of unregulated private money started pouring into it and yields of 12-18% became just not good enough. You might observe that right about the time, historically speaking, when we'd managed to accumulate giant performance databases about mortgage loans, we started offering "low doc, no doc and snow doc" deals with drive-by "appraisals" and automated underwriting and tiny due diligence sampling and every other mechanism we could think of to assure that there was, in fact, no data to be "transparent" about.

So now that we've "innovated" our way into a situation in which nobody has the first bloody idea what's going on with a huge portion of recently-originated mortgage loans, we've noticed that we've innovated our way into a situation in which nobody has the first bloody idea what's going on with the securities they're in or the CDOs that buy the tranches of the securities or the hedge funds that buy the tranches of the CDOs of the securities of the mortgages that were written on a hope and a prayer and a FICO. And this is a "teething" problem? Holy Mastication, Batman, you think this thing will improve if it grows some fangs?

Perhaps certain market participants need to be reminded why we call some of this stuff "nuclear waste." Generating a jillion-gigawatts of power is always a blast. Figuring out what to do with all the leftover plutonium-239 is a drag. How that only just got to be a problem of an "immature market" is beyond me.

And while we're on the subject of revisionist history, note this little gem courtesy of naked capitalism:

See that little footnote? Alt-A is "slightly less risky than subprime"?

Except for Calculated Risk and a few other cantankerous contrarian cranks, do you remember anyone in the last five years describing Alt-A as "slightly less risky than subprime"? My, my. How the worm turns.

KB Home Reports Second Quarter 2007 Loss

by Calculated Risk on 6/28/2007 09:16:00 AM

"Our second quarter results reflect the current oversupply of new and resale housing inventory, a difficult situation compounded by aggressive competition and continued weak demand. Housing affordability challenges and tighter credit conditions in the subprime and near-prime mortgage market have also exacerbated current market dynamics, keeping prospective buyers out of the market, slowing the absorption of excess supply and further delaying a housing market recovery. Pricing pressure intensified in many of our markets during the second quarter, compressing margins and requiring inventory impairment charges in certain of our communities."And for the quarter:

Jeffrey Mezger, president and CEO, KB Home, June 28, 2007 emphasis added.

Housing revenues of $1.30 billion were down 41% from the prior year's second quarter, the result of a 36% year-over-year decline in unit deliveries to 4,776 and an 8% year-over-year decrease in the average selling price to $271,600....

The Company reported a loss from continuing operations of $174.2 million or $2.26 per diluted share in the second quarter of 2007 ...

Wednesday, June 27, 2007

GDP Releases and Revisions

by Calculated Risk on 6/27/2007 07:53:00 PM

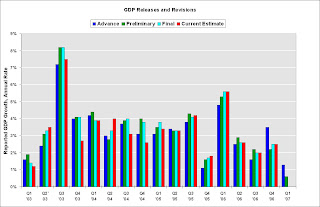

Tomorrow the "final" GDP report will be released for Q1. Of course the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) keeps on revising the estimate for some time, so "final" is just a name for the report.

In the near future, I'd expect the BEA to look into the suggestion by Business Week that offshoring has led to an overstatement of GDP in recent years. Most analysts think that Business Week is correct, but the overstatement is probably less than 0.2% per year.  Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

The BEA releases three GDP reports per quarter: Advance, Preliminary and Final. This chart shows the release numbers for each release, and also the current estimate for each quarter for the last few years.

Although it seems that the estimates change substantially, they are actually pretty similar from a macro perspective.

For tomorrow, I've seen estimates for the "final" Q1 report ranging from 0.4% to 1.5%. The consensus is 0.8%, mostly because of changes to net imports.

MISC Shelves $750M Bond Offering

by Calculated Risk on 6/27/2007 04:41:00 PM

From the Financial Times: Debt deals pulled as banks feel subprime chill

Companies are pulling financing deals across the globe, in one of the clearest signs yet that investors’ worries about rising interest rates and US subprime mortgages could be infecting other areas of the credit world and driving up the cost of corporate borrowing.UPDATE: Another interesting quote from MarketWatch: Hedge fund CEO: 'day of reckoning to come' in credit market

...

MISC, the world’s biggest owner of liquefied gas tankers on Wednesday shelved its $750m bond offering. The move came a day after US Foodservice, the American division of Ahold, the Dutch supermarket group postponed its $650m bond offering and Arcelor Finance put plans for its euro-denominated benchmark bond issue on hold, citing turbulent market conditions.

The bonds and loan deals were pulled after investors refused to buy them under the proposed terms, demanding higher premiums and more protection.

Stephen Green, chairman of HSBC, on Wednesday fuelled investor concern when he forecast that some large corporate deal was going to “end in tears” because of over-leverage. He warned the losses could be high because the parcelling out of risk to some many parties would make it more difficult to organise a financial reconstruction.

In an interview with the Financial Times, Mr Green admitted that he was “worried by the degree of leverage in some big ticket transactions nowadays” and felt that “something is going to end in tears”.

Eric Mindich, the chief executive of Eton Park Capital Management ... said the "day of reckoning" may be here, in reference to recent problems in the securitized debt markets. "There's dry timber out there," Mindich said at the Wall Street Journal Deals and Deal Makers Conference on Wednesday. "There are people's lives that are going to be changed by what happens."