by Calculated Risk on 7/09/2007 01:35:00 AM

Monday, July 09, 2007

Atlanta Foreclosures

From the NY Times: Increasing Rate of Foreclosures Upsets Atlanta

Despite a vibrant local economy, Atlanta homeowners are falling behind on mortgage payments and losing their homes at one of the highest rates in the nation, offering a troubling glimpse of what experts fear may be in store for other parts of the country.This is probably just the beginning of increasing foreclosure activity in Atlanta and the entire country.

...

A big reason the fallout is occurring faster here is a Georgia law that permits lenders to foreclose on properties more quickly than in other states. The problems include not just people losing their homes, but also sharp declines in property values, particularly in lower-income and working-class neighborhoods.

For example, a three-bedroom house near Turner Field, where the Atlanta Braves baseball team plays, fetched a high bid late last month of $134,000 at an auction by the bank that took possession of it. Almost three years ago, the new home was bought for $330,000.

Housing and Consumption

by Calculated Risk on 7/09/2007 12:07:00 AM

The "unexpected" sharp slowdown in Q2 Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) will likely restart the discussion of the impact of the housing slump - and less Mortgage Equity Withdrawal (MEW) - on PCE.

Some variation of the following graph will probably be part of the discussion. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

This graph shows MEW(1) as a percent of Disposable Personal Income vs. the Year-over-year change in Real PCE. An example of the use of this graph is presented as Exhibit 5 in this paper from Wells Fargo: Housing Bust Without A Consumption Bust???. The author writes:

Exhibit 5 shows virtually no relationship between real consumption growth and MEW. As MEW exploded between 1998 and 2003, consumption growth declined from over 5 percent to about 2 percent. As MEW has collapsed since 2005 from about 10 percent to about 3 percent, consumption growth has remained remarkably healthy at about 3.5 percent. Despite the widespread belief that MEW is a primary driver of consumer spending and the fear that any decline in MEW would certainly cause a collapse in consumption, this exhibit suggest consumer spending has been and continues to be little impacted by MEW.First, although the author is correct that there is no clear correlation between MEW and the change in real PCE during the period presented, perhaps he has it backwards; maybe the reason PCE was in the normal historical range for the last few years was because of MEW.

Of course the graph is flawed too. The author uses the YoY change for PCE (introducing a lag in PCE) and compares it to the current quarterly value for MEW (even though studies have shown MEW is spent over a number of quarters following extraction). This error in graphing led the author to this conclusion:

As MEW has collapsed since 2005 from about 10 percent to about 3 percent, consumption growth has remained remarkably healthy at about 3.5 percent.If declining MEW was going to have an impact on PCE, we wouldn't expect it to happen until several quarters after MEW declined. And since the YoY real PCE presentation introduces a mathematical lag, we would expect the graph to show a decline in PCE significantly after MEW declines - so the author's conclusion regarding "remarkably healthy" PCE while MEW is "collapsing" is, at best, premature.

Another perspective comes from Dallas Federal Reserve senior economist John V. Duca (written last November): Making Sense of the U.S. Housing Slowdown

The limited U.S. econometric evidence indicates that the strong pace of MEW may have boosted annual consumption growth by 1 to 3 percentage points in the first half of the present decade.[8] This implies that a slowing of home-price appreciation into the low single digits might shave 1 to 2 percentage points off consumption growth and 0.75 to 1.5 percentage points from GDP growth for a few years.

While these estimates provide an idea of housing’s potential economic impact, considerable uncertainty exists about how much a slowdown in MEW might restrain consumption growth. Key issues include how much home-price appreciation might slow, how much the deceleration would affect MEW and how much a slowdown in MEW would restrain consumer spending.

Dr. Duca presents this graph (as chart 4). Duca suggests that the recent increase in PCE as a percent of GDP might have been driven by MEW - and declining MEW might "shave 1% to 2%" off consumption growth for "a few years".

Duca's paper also includes references to much of the recent research on the impact of MEW.

Now we just have to wait for the "unexpected" decline in Q2 PCE!

(1) MEW calculations courtesy of James Kennedy, and are based on the mortgage system presented in "Estimates of Home Mortgage Originations, Repayments, and Debt On One-to-Four-Family Residences," Alan Greenspan and James Kennedy, Federal Reserve Board FEDS working paper no. 2005-41.

Sunday, July 08, 2007

The Compleat UberNerd

by Anonymous on 7/08/2007 09:14:00 AM

Frequently Imagined Questions:

What is an UberNerd post?

It’s a long post discussing everything you never wanted to know about random mortgage-related topics that are extremely important I felt like writing about at the time. UberNerd posts appear on this blog periodically on no known schedule.

What’s an UberNerd?

For those of you new to what passes for insider humor around this blog, an “UberNerd” is someone who is compelled to understand how things work in grim detail, even if the things in question are tedious in the extreme, like mortgage insurance policies. Not everyone who visits the blog is an UberNerd, or aspires to UberNerdity, but on the other hand those who display UberNerditude in the comment threads are treated with a respect bordering on lunacy. That’s just the way we are. Fortunately, we are not so intellectually intense that we cannot be distracted on a regular basis by rock videos and some damned fine figure skating.

What’s a Compleat UberNerd?

Someone who has read all these posts already and quotes them at tailgate parties. You can recognize them because their adolescent children walk ten paces ahead of them at the mall, in hopes that people will think they’re someone else’s parents.

Why are you reposting all these links?

Because I have been asked to over 100 times in the last six months or so and I just now got around to it. UberNerds may have a superficial resemblance to highly-organized people who carry day-planners, but at heart we are poets. And you know what poets are like.

Why can’t you just put a side-bar link to The Compleat UberNerd for us?

Because CR, being smarter than your average blogger, won’t give me access to the side-bars or any other part of the template. I get to play in the center column where I can’t hurt anything. You may therefore pester him and see how poetic his heart is.

What would constitute an “on-topic” comment to this post?

Beats me. Perhaps you could reminisce about what you were drinking the first time you read all the way through a great long post on mortgage insurance without being paid to do it. We also welcome testimonials from people who have tried some of this stuff out on the neighbors. Recipes are always welcome, too. It is traditional for the first comment in the thread to complain about the length of these posts.

The UberNerd Collection:

Mortgage Servicing

Negative Amortization

FICOs and AUS

Private Mortgage Insurance I

Private Mortgage Insurance II

Foreclosure and REO

MBS I

MBS II

MBS III

Delinquency and Default

Reverse Mortgages

Leverage, Ratings, and Forced Unwind

Mortgage Origination Channels

Saturday, July 07, 2007

It's Not the Default, It's the Deleveraging

by Anonymous on 7/07/2007 01:38:00 PM

More proof that Australians are smarter than us Americans: here's an article from the Sydney Morning Herald on CDOs that is not stupid. I found the discussion of credit spreads a bit foggy, it is true, but since the issue is either absent or entirely mangled in every other mainstream media piece I've seen on the subject, I can accept foggy. In any case, I recommend the whole thing if you're new to the leveraging issue.

Ibbetson says there are three parties who need to shoulder blame for the current imbroglio, and all are equally culpable: Bear Stearns for leveraging the fund so highly, banks for lending the money to enable the leverage, and investors for buying into an investment that they really should have known could be exceptionally risky.

I guess they haven't figured out down in Oz that it's all the rating agencies' fault. John Mauldin has some ideas on that in this week's newsletter:

When a corporation gets a rating there are audits, not to mention regulators that are there overlooking the data upon which the ratings are based. But no one was looking at the data used to create the ratings on RMBSs and CDOs, to make sure there was some type of reasonable similarity or standard of the securities being rated and the databases used to do the risk analysis.

Subprime loans made in 1999 or 2002 were significantly unlike those made in 2004-2006. At the end of 2006, many subprime loans were defaulting in only one or two months from the date of the loan. No-documentation "liar's" loans were common. Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM) loans, made where the applicant could clearly not make the payments when the interest rate reset, were common. Thus, the past performance the ratings were based on was significantly different than for the crop of then-current loans, and was substantially misleading. We are talking an apples and cumquats type of difference here.

So, the rating process was not the same as the ratings that were used in the corporate world. But the problem is that the ratings used the same designations. Instead of creating a whole new type of rating standard (say, using numbers like "CDO rank 1-10"), they used the same designations that bond investors were used to.

I think it is disingenuous for a rating agency to explain the difference in paragraphs 457-503 in 7-point type and dense legalese in their disclosure document. Investors had (and should have) a certain level of expectation when the designation "AAA" is used. GE and Exxon types of expectations.

I am not expecting infallibility here. Let's make it clear that the rating agencies have made mistakes in the past and will make them in the future. You do your best, and in general I think they do an excellent job given the pressures and the vagaries of the business. (I certainly have made a few mistakes here and there in my career that I would not make today. And I will make more in the future. We live and learn.)

The problem is in allowing the confusion of rating a CDO as you would a GE or Exxon. I think Dann has a point when he says the rating agencies aided and abetted the investment banks. And that point gets even bigger when we are talking about CDOs.

When you pool BBB tranches into a CDO and now turn 80% plus into AAA at the touch of an algorithm, based on faulty assumptions, someone somewhere should have raised an eyebrow.

This is not going to end up pretty. You can bet that 20-20 hindsight is going to kick in here as the regulators and various attorneys general get involved. The rating agencies may be able to justifiably say that they were doing exactly what they said they were doing in the disclosure documents. But then someone at the investment banks (especially those that owned subprime mortgage brokers and should have been able to see the deteriorating quality of the loans) should maybe have thought that the default rates would change and therefore should have used different assumptions.

But then, that would have killed what was a very profitable business. And everyone was doing it, so to unilaterally disarm when every other investment bank and agency was doing the same thing evidently did not cross the mind. Last year there were $500 billion in CDOs sold, and half of it subprime. In June, there was only $3 billion. And you can bet there was no subprime in them.

As an aside, the rating agencies are starting to downgrade the CDOs. Of the pool of securities created from 2006 subprime mortgages, Moody's has downgraded 19% of the issues they've rated and put 30% on a watch list. That will grow.

And let's look at the investment banks. Creating and selling CDOs was a particularly juicy business. I have heard, but not verified, that sales commissions were running 5%. You can bet the banks were making at least as much. Put together a $250 million CDO and sell it to institutions, pension funds, insurance companies, and hedge funds, put some of the equity portion into your own portfolio, and you could generate substantial profits and commissions. Rinse. Lather. Repeat.

Saturday Rock Opera Blogging

by Anonymous on 7/07/2007 10:53:00 AM

Sorry, friends, but no rock blogging today. For those of you who missed the news, Beverly Sills died on July 2, 2007.

Like many, many people, I first encountered the joy of opera watching Sills on TV. More than anyone else, she was responsible for demystifying operatic culture and inviting a mass audience into a world of beauty without a hint of condescension or pedantry. Her humor and gallantry have been and will remain as legendary as her beautiful voice.

Goodbye, Bubbles.

Lender-owned Homes on the Rise

by Calculated Risk on 7/07/2007 12:46:00 AM

From the San Jose Mercury News: Once rare in valley, lender-owned homes on the rise

REOs, once rare in Silicon Valley, may soon contribute to lower home prices in some neighborhoods.

...

In May, $2.8 billion worth of California real estate went up for sale in foreclosure auctions, according to ForeclosureRadar.com, a Discovery Bay company that sells foreclosure information to subscribers. Of that amount, about $2.6 billion worth failed to find buyers, and so became bank-owned. The figures represent the total value of the outstanding loans that went up for auction.

Those figures are way up from early this year. In January, for example, $1.49 billion worth of property was auctioned statewide, and $1.32 billion went back to banks. January is typically a busy month because trustees usually refrain from foreclosing during the December holidays.

...

An estimated 8 percent of homes for sale - or about 450 houses and condos - in Santa Clara County as of June 30 were "distressed" in some way - either being sold in a "short sale," or in foreclosure or as REOs ...

Friday, July 06, 2007

Delinquencies and Defaults for UberNerds

by Anonymous on 7/06/2007 04:20:00 PM

I have no intention of exhausting the topics of delinquency and default today. My goal is rather more modest than that; I merely want to introduce to the non-mortgage-backed-security world a few definitions of terms, in hopes that perhaps some of these startling numbers being thrown around in the press can be interpreted. Besides that, it's too early in the day to start drinking, so we might as well waste our time being educated.

The fact is we see a lot of press reports quoting delinquency rates as if they were default rates. A large part of the problem, besides the general lack of expertise of a lot of business reporters, is that generally the only freely-available numbers to report are delinquency rates expressed as a percentage of a given book of business. There are other, more sophisticated ways of measuring credit loss risk than a simple bucketing of loans into categories of "current" and "delinquent," but these specialist calculations are generally not available to those who do not pay for subscriptions to analytic services. One of the most important calculations is the "roll rate," or the rate at which current or delinquent loans are "rolling" into the next bucket (current to 30 days, 30 days to 60 days, etc.). Another hugely important measure is the default rate: the projection of actual defaults for a given bucket of current or delinquent loans.

It is not possible, of course, to understand default rates without understanding the distinction between "delinquency" and "default." There are alternative ways of measuring delinquency (the "OTS method" and the "MBA method"), but it comes down to the same thing: a delinquent loan has missed at least one scheduled payment. Therefore, a "30-day" delinquent loan is past due by one payment as of the report date; a "60-day" is past due by two payments, and so on. The trouble is that these may or may not be consecutive or even most recent payments.

30-day delinquencies are very volatile. They are often seasonal, for one thing, and they can very often turn into what underwriters call a "rolling 30" ("rolling" in this case is not to be confused with a "roll rate" of 30 to 60 days delinquent). Imagine a borrower who is current through the June payment, misses the July payment, makes the August payment, and continues on through the end of the year making a payment each month, but never making up that missed payment from July. That borrower would be considered "current" in July (you aren't "delinquent" for our purposes until you're at least 30 days delinquent), 30 days deliquent in August, 30 days delinquent in September, and so on to the end of the year. It doesn't matter how far in time you get from that missed payment: you only missed one, so you are never on any given reporting date more than 30 days down.

You can have "rolling 60s," but servicers are rather less likely to put up with them than rolling 30s. At some point a servicer has to decide whether to "accelerate" the loan or not, and that's always a tough call with a rolling delinquency, since the very fact that it's "rolling" means that the borrower has resumed making payments; the borrower simply has not caught up with the misssed payment or payments. These borrowers are generally the best candidates for a modification. The lender can add the missed payment to the loan balance, which brings it "current" again and stops the accumulation of late fees and endless collection calls, among other things.

Things like these "rolling 30s" do make it unwise to use simple metrics like a 30-day delinquency rate (the percentage of loans by balance or units in a given pool or portfolio that are 30 days delinquent as of the report date) to predict future losses, since a simple delinquency rate calculation cannot distinguish between a "new 30" and a "rolling 30," and loans that are 30-days delinquent last month can certainly become current this month, as borrowers do sometimes make up missed payments. This is the main reason that most reports distinguish between "delinquency" and "serious delinquency," the latter generally defined as 60+ or 90+ lates.

As a general rule, most servicers do not begin foreclosure proceedings until a loan is 90 days delinquent. This isn't a "magic number," it's just a rule of thumb. For our purposes, one thing it means is that a servicer will usually report separately on loans "90 days delinquent" and "loans in foreclosure." "In foreclosure" means the loan is in a process, often a long one, that starts with the filing of a foreclosure notice and ends at an auction on the courthouse steps. Because there can be loans that are 90 days or more delinquent that are not in foreclosure--there could be forbearance or short sale or other workout arrangements in process, or a bankruptcy stay could be delaying the foreclosure filing--it is important to verify, with any set of numbers you look at, whether a "delinquent" bucket includes loans in foreclosure or not, to avoid double-counting when the numbers are totaled.

It makes a big difference, because the "roll rate" or likelihood of eventual default of a 90-day delinquent loan is not the same as the "roll rate" of a loan in foreclosure. Two such loans might actually be past-due for the same amount of time, but the fact that the servicer initiated foreclosure proceedings in one case but not the other is, precisely, a judgment of relative likelihood of default. Plenty of people have plenty of suspicions about how wise some of these servicer judgments are--that's the whole uproar over modifications and forbearance in a nutshell--but the point is that once a servicer files a foreclosure notice and begins the process, ultimate default of the loan is more likely just because the process is in motion.

This is probably the point where we should define "default." That term has an everyday legal definition that may confuse people in the context of credit losses on mortgage securities. In everyday terms any violation of a contract, including a mortgage, is a "default." You can, technically, be "in default" of your mortgage by failing to pay a $17.50 HOA assessment or moving out of your home, even if you keep your mortgage payments current. For purposes of calculating loss probability on a pool of mortgage loans, "default" means something much more specific: a defaulted loan, according to the Bond Market Association, "no longer pays principal and interest and then remains delinquent until liquidated." There are many ways a loan can liquidate: it can be foreclosed and the property purchased by a third party; it can become REO and the REO liquidated by sale to a third party; it can be a short sale or short payoff (the latter being a refinance of a delinquent loan in which the noteholder accepts less than full payoff).

You have to remember that "default" does not mean "loss." Imagine a $100,000 loan which becomes delinquent, is foreclosed, becomes REO, and is ultimately liquidated by sale of the REO. This loan is defaulted, but the loss to the noteholder might be only $20,000 after application of sale proceeds. That would mean that $80,000 comes back to the noteholder in the form of principal repayment. The importance of measuring defaults accurately is that it allows the security accounting to distinguish between normal or voluntary prepayments (principal returned via a performing loan's refinance or sale of the subject property) and involuntary prepayments via recovery from liquidation of delinquent loans. But the purpose of reporting default balances is not to equate defaults with net losses. The latter will depend on "loss severity," or what percentage of the outstanding loan balance is not recovered in liquidation. That, obviously, is an issue of home prices and servicer efficiency.

The problem, then, is getting from delinquencies to defaults, in terms of projecting what ultimate losses will be. Here's an example, from Fitch, of how one might project losses on a seasoned mortgage pool:

The first column puts the loan pool in "buckets" according to delinquency status as of 18 months age of the pool. The second column projects lifetime defaults for each bucket, using a series of assumptions and calculations based on historical experience, performance of this specific pool in its first 18 months compared to initial projections, home price appreciation estimates, and so on. The projected defaults range from 11% for "current" loans to 76% for "foreclosure" loans (the REO category is 100%, since once foreclosure is completed there is no possiblity of a loan becoming current again, and the definition of default is the liquidation of a delinquent loan).

The third column is important, because while "current" loans have the lowest likelihood of default (11%), they are the largest bucket in the pool, and so "current" loans that ultimately default are projected to be 9.1% of the pool, as opposed to "foreclosure" loans with the highest likelihood of default (76%), which are projected to be 2.9% of the pool.

The fourth column is the loss severity, or the percentage of the loan balance that is not expected to be recovered after liquidation. For the purposes of a table like this, remember that it is an average: some loans may have much higher recoveries, and some much lower. Obviously it is a crucial calculation for determining ultimate losses.

The final column gives you expected loss as a percent of the current pool balance, which in this example is 63% of the original balance. (The original balance has been reduced by 37% prepayments.) The projected loss as a percentage of original pool balance is 5.25%, or 7.1% of current pool balance.

Note that the pool has already experienced losses of 0.77% in its first 18 months. That does not necessarily mean that the lowest-rated tranche has taken a write-down; in fact, overcollateralization and excess spread on most deals should be more than sufficient to cover losses of 0.77% in 18 months without "breaking into" the principal balance of the lowest-rated tranche. The significance of the projections you see on this chart are, for an actual bond, a question of how the timing of projected losses play out as well as the adequacy of the OC and excess spread. It is possible that this pool will never see actual principal write-downs, even if it achieves losses as projected in the chart, if its OC and excess are adequate. (They may well not be adequate, but this chart doesn't tell you that one way or the other.)

It should be clear, but let me be tedious: the projections of loss in the example here are over the remaining life of the pool, not over the next year or month or week. Such projections may or may not be accurate: projections are projections, not divinations. I bring this example up not to suggest that it produces a loss prediction we can use as a rule of thumb: this is a specific example pool and your mileage may vary on a different pool. My purpose is to give us some perspective on the conclusions some people like to draw from looking at delinquency statistics. Delinquency reports are just a snapshot in time; they are not, themselves, predictions. So the weenies who have been going around trumpeting the fact that, say, 83% of subprime loans are currently current, as if that meant that the 83% will never become delinquent or defaulted in the future, are, well, weenies.

As are some of these opposite-side weenies who seem to think that a 17% delinquency rate means 17% losses to a pool. That would be true only if the "roll rate" of all delinquencies-to-default is 100% and all foreclosed homes have a sales price of $1.00. Not likely, to say the least. Even if the calculations in this example pool are off by a great deal--if the true total defaults end up 30% instead of 20% and the severity is 50% instead of 35%--you get a cumulative loss of 15% of current balance. You can, if you're like me, be convinced that there are some really, really cruddy pools out there that will have numbers at 18 months that look a lot worse than this example from Fitch. I do not doubt that there will also be at least a few that do better. Fitch's assumptions about home price appreciation may be off a little or off the wall: that's one reason we keep watching these trends so closely here at Calculated Risk.

It is particularly annoying when we see people throwing around delinquency numbers as if they were loss percentages, and then applying that number to the total outstanding balance of all subprime securitizations to come up with some scary-looking number in the billions, without taking into account, among other things, the original expected loss on the pools. Not even the meanest (sane) critic of the rating agencies accuses them of having predicted no losses at all when these deals were originally rated. If that were so, there'd be no OC or excess spread and all bonds would be AAA. I think a few folks are getting worked up over the failure of the rating agencies to downgrade some of these pools that have what look like high delinquency rates, without questioning the extent to which those rates are or are not in excess of the original projections. Looking at the example pool above, for instance, you see a projected loss after 18 months, but what you don't see is what the original projection was. Without that, there's no way to conclude that this pool deserves a downgrade.

You might want to plow all the way through the document from which this example is taken if you want to know more about how a delinquency analysis is part of a potential downgrade of a security. It's called "U.S. Subprime RMBS/HEL Upgrade/Downgrade Criteria," and it is available here to registered users of Fitch's website.

Meritage Homes: Falling Revenue, Cancellations Increasing

by Calculated Risk on 7/06/2007 09:53:00 AM

"Weak demand and high inventory levels have increased competition among homebuilders, pressuring margins despite reductions in new home starts, lot supplies and operating costs."From a Meritage Homes press release on orders:

Steven J. Hilton, chairman and CEO of Meritage Homes.

Preliminary results for the quarter include approximately $569 million home closing revenue, $502 million home orders, and $1.2 billion ending backlog. These results represent declines of 37%, 28% and 39% from the second quarter of 2006 ...And on cancellations:

Cancellations rose to approximately 37% of gross orders for the quarter, compared to 32% in the second quarter 2006 and 27% in the first quarter 2007.

June Employment Report

by Calculated Risk on 7/06/2007 08:37:00 AM

The BLS reports: U.S. nonfarm payrolls rose by 132,000 in June, after a upward revised 190,000 gain in May. The unemployment rate was steady at 4.5% in June.  Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

Here is the cumulative nonfarm job growth for Bush's 2nd term. The gray area represents the expected job growth (from 6 million to 10 million jobs over the four year term). Job growth has been solid for the last 2 1/2 years and is near the top of the expected range.

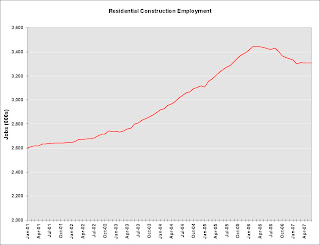

The following two graphs are the areas I've been watching closely: residential construction and retail employment.

Residential construction employment was flat in June, and including downward revisions to previous months, is down 135.3 thousand, or about 4.0%, from the peak in March 2006.

Note the scale doesn't start from zero: this is to better show the change in employment.

Retail employment lost 24,200 jobs in June. As the graph shows, retail employment has been fairly flat in recent months. YoY retail employment is slightly positive.

The expected reported job losses in residential construction employment still haven't happened, and any spillover to retail isn't apparent yet. With housing starts off over 30%, it's a puzzle why residential construction employment is only off about 4%.

Thursday, July 05, 2007

Wells Fargo Shuts Down Division

by Calculated Risk on 7/05/2007 06:37:00 PM

Here is an email Wells Fargo sent out last week. Note the shut down date was last Friday. I couldn't find any stories on this division (email via a reliable source):

If you have any loans that you would like to submit, they need to be sent by way of our Secured Document Delivery system ("SDD" e-mail address) into our Baton Rouge Operations Center and rec'd before 5 pm CT tomorrow, Friday, June 29th.

WELLS FARGO has decided not to continue operation of this division. However, we will be honoring the pipeline, and funding your loans for the next 60+ days. If you have questions about loans in process, purchase advice, etc… (info removed)

I will always be available by cell phone @ (phone number removed). This e-mail address will be "turned off" within the next 24 hours.

It was a pleasure doing business with you, I hope to do so in another capacity (WHEN this market turns back in our favor)

Troy Alexander

Correspondent Lending

WELLS FARGO Home Mortgage

(contact info removed)

...

For your protection, we remind you that this is an unsecured email service, which is not intended for sending confidential or sensitive information.