by Anonymous on 1/19/2008 10:00:00 AM

Saturday, January 19, 2008

GuestNerds: The Pig and The Balance Sheet

We get a lot of questions about accounting issues these days. People are concerned about accrual accounting, particularly as it relates to Option ARMs or negative amortization and the income treatment of accrued but unpaid interest. This issue always butts up against the question of how mortgage holders reserve against losses on loans, or determine the extent to which capitalized interest is or is not ultimately collectable. We've also posted some news stories regarding the uproar over SFAS 114 treatment of modified mortgages, which really get down into the weeds in terms of mortgage accounting and which are, therefore, hard to follow without a basic understanding of general mortgage asset accounting. Finally, a number of people have been asking, as we keep seeing more and more reports of write-downs at banks and investment banks, how long this writing-down is going to go on, and how it is really calculated.

Some of you--bless your lovely hearts--may be entirely innocent of any background in accounting. You may be struggling to follow the conversation in part because you make the common civilian error of forgetting that bank accounting is "backwards." To you, a loan is a liability and a deposit account is an asset. To the bank, the loan is an asset and the deposit account is a liability. It does get more complicated than that, but it never makes any sense at all until you do get past that point.

Some of you, I know, come from the "real economy," or "widget-accounting," and you are stuggling with accounting concepts that make sense to you in terms of widget makers (or retailers), like inventory and receivables and warehouses, but become puzzling when they are applied to financial accounting. Some of you may be small business owners who work on a cash basis, not an accrual basis, so you may find financial accounting even more impenetrable.

I, who was never allowed into the accounting department unescorted am not an accountant, quite often struggle to make these things clear. Fortunately, our regular commenter Lama, who is a real accountant, has offered us a splendid GuestNerd post which walks us through the basics of accrual accounting, reserves, income, and asset valuation. I have added a few comments of my own, strictly from a banking perspective. Another of our regulars, the mighty bacon dreamz, has contributed illustrations to support Lama's text. I think you will find them enlightening.

Lama On Accrual Accounting and Reserves:

To understand how "other amortization" works, I guess you first need to know how accrual accounting works. Most individuals calculate their taxes based on cash basis accounting. You recognize income when you receive the cash (or check); you recognize expenses when you pay cash. Companies with simple cash transactions and not much equipment or inventory do not vary much if they use cash or accrual accounting (think newsstands, maybe a small consulting company).

Accrual accounting means you recognize revenue when earned, expenses when incurred. A gas station would not incur an expense when they purchase gas for resale. That station would incur the expense at the time the gas was sold. That’s because the gas’ cost was a cost to produce the sale. In the time between the purchase and subsequent sale, the company holds the gas as inventory as an asset on its balance sheet.

Another concept to keep in mind is that every asset on a balance sheet has a base and a reserve. The base asset value is the easy part. If someone borrows $100,000, you have a schedule with the $100,000 on it. The loan cost you $100,000 to make. If someone owes you the $100,000 and $5,000 accrued (unpaid) interest, now your schedule will have $105,000 as a current loan value.

Making a loan on the accrual basis means the lender is earning income based on what he is owed, not based on how much cash he receives, but how much the borrower owes. If there’s a $100,000 loan at 5%, the borrower owes $5,000 after one year. If the borrower pays $6,000, the loan balance is $99,000 with $5,000 paying interest and $1,000 paying principal. If the borrower pays $4,000, the loan balance is now $101,000, with $5,000 paying interest and $1,000 increasing the amount of the loan. That’s all there is to calculating the base asset. This is in keeping with every related principle of accrual accounting and has been done the same way since The Mortgage Pig wore short pants.

Now the reserve or fuzzy area. A reserve is the amount by which you will devalue the amount you record as the base asset. There are 3 basic ways to calculate a reserve. It’s possible to use any combination of 1, 2 or 3 within a portfolio. On debt instruments a company intends to hold (until maturity or involuntary termination), the reserve will be based on both Net Present Value of cash flows and collectability. The most accurate method is to specifically identify impaired assets. If you only think you’ll collect $90,000 NPV, the value is $90,000. Repeat the same for each loan. One might have a value of $0. [Tanta: this involves a credit analyst reviewing each loan at each reporting period, generally quarterly, to determine whether or to what extent it is impaired. You will find this method used on commercial portfolios, where there are fewer units of much larger loans which may not be homogenous or easily comparable to each other.]

The second method is a percent reduction of loan values based on historical experience. Say, if instruments of a certain type typically devalue by 5%, you’d apply that to the assets in the classification. Split the classified loans into as much detail as you think appropriate (there’s some detail in this area we don’t need today). [Tanta: this is the method typically used for loans classified as residential 1-4 family mortgages. In any but the tiniest portfolios, there are too many units to examine individually, and the guidelines and underlying collateral for residential 1-4 family are (supposed to be) homogenous enough that classification or grouping of loans for analytical purposes is considered sound practice as well as obviously efficient practice.]

The third type of reserve is called a general reserve. It is simply an educated guess applied to the entire portfolio. A manager might apply this on top of the other two types. This is also known as wetting your thumb and checking which way the wind is blowing. Years ago, the chairman of the SEC decried general reserves as “Cookie Jar” reserves and “Rainy Day Funds” and their use substantially diminished. Oh, in case you do some research on your own, Reserves = Allowances. [Tanta: in the context of banking, you will find loan reserves referred to as Allowances for Loan and Lease Losses or ALLL.]

The loan balance you see on the balance sheet or support schedule is the net of the base less reserves.

So, how does this affect Income? In accounting, everything is a transaction. Hence the Debits and Credits, which are just names. Your credit card company says “we’ll credit your account.” That means they are posting a credit to their Assets account “Loans." Assets are Debit accounts, so increases in Assets are Debits, decreases are Credits. Revenue is a Credit account, so increases in Revenue are Credits, decreases are Debits.

Reserves for Loans Losses is a Contra-Asset account. Contra-assets are credit accounts that piggyback off Asset accounts. That is to say, an increase to the Reserve is a decrease (credit) to the net Asset. The sister account to Loan Reserves on the Income Statement is the expense called "Provision for Credit/Loan Losses." To balance the journal entry, you post a debit to the expense, increasing it. So, in our example loan above, the base Asset is still $100,000 and the Contra-asset is $10,000, net $90,000. Expenses in the Income Statement will take the other side of the journal entry and increase (debit) for $10,000. In theory, there could be income from a reduction of the allowance account. I don’t see that happening these days. [Tanta: that would be the “cookie jar” problem: the temptation to over-reserve in very good times, which reduces current income to just “good,” in order to reduce those unnecessary reserves in future bad quarters, which would increase income in those quarters from bad to “good” (or just “acceptable,”) and therefore make the income over time appear more stable, which makes Wall Street analysts happy. It is not likely that anyone intentionally over-reserves in bad times, since it’s hard to withstand the effect that has on current income, whatever it might do for future quarters. I certainly do not believe that banks and thrifts were over-reserving during the boom, and as each quarter’s reports come out we see they are steadily increasing ALLL. This does not look like “smoothing” income to me.]

Something very likely to happen is that, in addition to principal, jingle mail senders will not be paying interest. If the bank can foresee a future default on our loan’s interest payments of $2,000, then they record a liability for $2,000 (not a reserve to an asset) and record a debit to Interest Income for $2,000 in the current year, reducing revenue.

Now, our total Net Income is reduced by $10,000 + $2,000, $12,000. Unless and until Cash is loaned or received, there is no effect on Cash.

It’s clear that there is some estimating and guessing done within the reserve calculations and bank managers are going to do all in their power to avoid restatements as none of them ever could have known (enter specific affecting crisis here). So if you want some moral outrage, don’t vent it on the accrual method, vent it against the reserves (more specifically, the people who estimate them). [Tanta: this is why I keep saying that the accounting treatment we are seeing for OAs is not "accounting games." The issue isn't the accounting rules for non-cash income; the issue is what assumptions went into estimating how much of that deferred interest is ultimately collectable.]

Lama On Asset Valuation:

First of all, most assets are required to be valued at the lower of cost or market (assuming a market exists). Usually, the more liquid an asset, the closer the market value will be to cost. Cash is the logical extreme as cost always equals market. Then you have Accounts Receivable which is usually proximate. Next, Inventory can closely trace the actual cost. That is, it should, but companies buy things they can’t sell, they redesign products they make, causing component inventory to be worth little to the company. Even items that have value to someone else might be valued at very little because there’s too much cost involved in finding a buyer and transportation. I once audited a company that had hundreds of thousands of titanium pipes valued at cost. Well, they had no use and no customer for them. The best offer they got was from the original vendor, 15% of cost. That was my number. So it goes onto Capital/Fixed Assets. Here, market value is usually not important. Heavy equipment that might make lots of money frequently has a low resale value and huge transportation costs if it was sold.

Our debt instruments are, by their nature, very liquid. If the holder is interested in selling, they should be valued at market. If you don’t like the current market price, then the instruments are not for sale . . . ok, you don’t mark them to market, you mark them to discounted cash flows. This is where the “mark to make believe” has been and is happening.

[Tanta: banks and thrifts in the mortgage business have two categories of mortgage assets: HFS (held for sale) and HTM (held to maturity). The former is “inventory” and the latter is “portfolio investment.” HFS is marked to market. As Lama says, if you aren’t marking to a market price, then apparently you aren’t really trying to sell anything here (home sellers, take notes on this part). Eventually, if you cannot (or will not) sell your HFS pipeline, you will need to transfer it to HTM (if you have the capital necessary to hold loans to maturity), and at that point you record the loan at the lower of cost or market. In this case there is an original “write-down” of the asset if current market value is less than cost. After that, further write-downs will be necessary at each reporting period, as Lama indicates above, if the assets become impaired (or more impaired than they were when you originally put them on the books). So what we are reading in the news about write-downs of mortgages and mortgage-related assets these days involve a combination of mark-to-market adjustments (for anything in “inventory” or being taken out of HFS to HTM) and impairments of assets that have deteriorated since the asset value was originally recorded. No one is allowed to take a “once and for all” write-down of a mortgage asset; ALLL is based on your best projections of realized losses in the next 12 months (adjusted each quarter). Theoretically, every loan you own is subject to further write-down each quarter if in fact your estimate of collectability continues to deteriorate.]

Friday, January 18, 2008

Fitch Downgrades 420 ABS Bonds

by Calculated Risk on 1/18/2008 09:05:00 PM

From MarketWatch: Fitch Downgrades 420 ABS Bonds Following Ambac Rating Downgrade; Watch Negative (hat tip Risk Capital)

Fitch Ratings downgrades 420 classes of asset-backed securities (ABS) Additionally, the ratings remain on Rating Watch Negative by Fitch. This action follows Fitch's downgrade of the ratings on Ambac ...Check out the ABS list at MarketWatch: aircraft transactions, student loan bonds, auto loans - the impact from a bond insurer downgrade is widespread.

Finally it feels like a Friday night!

Fed Funds: Odds Moving Towards 100bps Rate Cut

by Calculated Risk on 1/18/2008 08:08:00 PM

According to the Cleveland Fed, the market expects a 75 bps cut in the Fed Funds rate on January 31st, with the odds of a 100bps rate cut rising rapidly. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

Source: Cleveland Fed, Fed Funds Rate Predictions

It is no longer a tossup; market expectations are for a rate cut to 3.570% or almost 75bps.

Professor Tim Duy argues: Odds Still Favor a 50bp Cut

I think odds still favor 50bp – it would be more consistent with the Fed’s medium term objectives, and help maintain policy flexibility over the first half of the year. Moreover, this cut will do nothing to support the current environment, and the Fed needs to be looking at what it means for 2009. The case for 75bp relies largely on meeting market expectations, expectations that may be driven by an excessive level of fear.If 75 bps is based on "an excessive level of fear", I wonder what Tim thinks of 100bps?

More on Ambac Rating Downgrade

by Calculated Risk on 1/18/2008 06:15:00 PM

From Christine Richard at Bloomberg: Ambac Insurance Loses AAA Ranking at Fitch Ratings

Ambac ... became the first bond insurer to lose its AAA rating after Fitch Ratings downgraded the company.Moody's and S&P are also reviewing the bond insurers, see:

Ambac Assurance Corp. was lowered two levels to AA and may be reduced further ... Fitch said today in a statement. ... The downgrade throws doubt on the ratings of $556 billion in municipal and structured finance debt guaranteed by Ambac.

...

The seven AAA rated bond insurers place their stamp on $2.4 trillion of debt. Losing those rankings may cost borrowers and investors as much as $200 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

S&P: Bond Insurer Review to be Completed Next Week

Moody's: Ambac Under Review for Possible Downgrade

The Wall Street "Parade of Write-Downs"

by Calculated Risk on 1/18/2008 04:32:00 PM

From the WSJ MarketBeat by David Gaffen: Writedowns Surpass $100 Billion. Note: Here are the write-downs in a spreadsheet.

The great 2007-2008 parade of writedowns, which was hovering around the $100 billion mark already, has pushed far past that thanks to Merrill Lynch’s $14.5 billion in assets lost ...There are many more write-downs to come.

The thing is, the writedowns aren’t finished. Several firms retain significant exposure to subprime, such as Citigroup, which still has $37 billion in subprime exposure. Back in November, Goldman Sachs economist Jan Hatzius estimated about $200 billion in mortgage-related losses on the big banking balance sheets. (He was ridiculed for this and charged with “talking his book;” but the figures show his gloomy forecast is on the way to being fulfilled.)

Housing: Seasonal Inventory

by Calculated Risk on 1/18/2008 03:44:00 PM

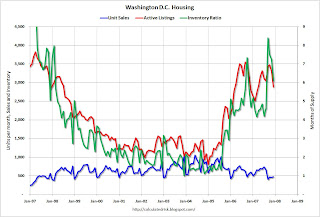

To illustrate the seasonal pattern for housing, here is some housing data (through December) for Washington D.C. sent to me by reader dc1000. The data shows a 13% decline in inventory, from 3,307 units in November to 2,880 units in December. Sales for December were at the lowest level since dc1000 has been keeping statistics, starting in '97. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

This graph shows the sales, inventory and months of supply for Washington, D.C.

Note the sharp decline in inventory in December (and months of supply).

Inventory and "months of supply" are not seasonally adjusted in this calculation. The normal seasonal pattern (nationally) is for inventory to decline about 15% in December as sellers remove their homes from the market for the holidays.

Remember this when the National Association of Realtors (NAR) announces that inventory declined in December!

Note: in this case both sales and inventory are NSA (not seasonally adjusted). So "months of supply" is also not seasonally adjusted. The NAR seasonally adjusts sales, but not inventory. So the NAR "months of supply" calculation is a little weird; a seasonally adjusted number being compared with a non-seasonally adjusted number. For new homes sales, the Census Bureau seasonally adjusts both sales and inventory.

Fitch cuts Ambac rating to AA

by Calculated Risk on 1/18/2008 02:46:00 PM

From MarketWatch: Fitch cuts Ambac rating to AA from AAA

This will probably mean some more write-downs from the banks.

Added: For a discussion of the possible implications, see Alistair Barr's piece at MarketWatch: Bond-insurer woes may trigger more write-downs (hat tip Barley)

Just when you thought it was over, trouble in the $2.3 trillion bond-insurance business could trigger another wave of big write-downs from banks and brokerage firms, experts said Friday.

...

Bond insurers agree to pay principal and interest when due in a timely manner in the event of a default -- a $2.3 trillion business that offers a credit-rating boost to municipalities and other issuers that don't have AAA ratings. Without those top ratings, their business models may be imperiled.

...

The destruction of the bond insurers would likely bring write-downs at major banks and financial institutions that would put current write-downs to shame," Tamara Kravec, an analyst at Banc of America Securities, wrote in a note Friday.

MBA Report On Workouts

by Anonymous on 1/18/2008 12:15:00 PM

The MBA has a report out on foreclosure and workout data from the third quarter of 2007 (thanks, Clyde!). The data is in tabular form that's a bit unwieldy, but here's part of the summary:

[D]uring the third quarter the approximately 54 thousand loan modifications done and 183 thousand repayment plans put into place exceeded the number of foreclosures started, excluding those cases where the borrower was an investor/speculator, where the borrower could not be located or would not respond to mortgage servicers, and when the borrower failed to perform under a plan or modification already in place.What jumps out at me:

Of the foreclosure actions started in the third quarter of 2007, 18percent were on properties that were not occupied by the owners, 23 percent were in cases where the borrower did not respond or could not be located, and 29 percent were cases where the borrower defaulted despite already having a repayment plan or loan modification in place. . . . the degree to which invest investor-owned properties drove foreclosures in the third quarter differed widely by state and by loan type. They ranged from a high of 35 percent of prime ARM foreclosures in Montana to a low of 6 percent of prime fixed-rate foreclosures in South Dakota. For the nation, investor loans comprised 18 percent of subprime ARM foreclosures, 28 percent of subprime fixed-rate foreclosures, 18 percent of prime ARM foreclosures and 14 percent of prime fixed-rate foreclosures. Table 6 shows, for example, that while 11 percent of foreclosures on prime ARM and prime fixed-rate loans were on non-owner occupied properties, the percentages for subprime loans were almost double that — 19 percent for subprime ARMs and 20 percent for subprime fixed-rate. In Ohio, a state that has had some of the highest foreclosure rates in the nation, investor owned properties accounted for 21 percent of subprime ARM foreclosures and 34 percent of subprime fixed-rate foreclosures, versus 18 percent of prime ARM and 14 percent of prime fixed-rate foreclosures. Nevada had among the highest investor-owned share of foreclosures, with investors accounting for 36 percent of subprime fixed-rate foreclosures, 18 percent of subprime ARM foreclosures, 24 percent of prime ARM foreclosures and 14 percent of prime fixed-rate foreclosures.

Borrowers who could not be located or who would not respond to repeated attempts by lenders to contact them accounted for 23 percent of all foreclosures in the third quarter, 21 percent of subprime ARM foreclosures, 21 percent of subprime ARM [sic; FRM?] foreclosures, 17 percent of prime ARM foreclosures and 33 percent of prime fixed-rate foreclosures. Thus, as a percent of foreclosures, the inability to get a borrower to respond to a mortgage servicer is a much bigger problem for prime-fixed rate borrowers than for subprime borrowers. Again the results differed widely by state and loan type. The highest was 69 percent for prime fixed-rate foreclosures in Oklahoma versus a low of 7 percent of prime ARM foreclosures in Wisconsin. Table 7 shows that in Ohio and Michigan, 25 and 26 percent respectively of all foreclosures started in those states were for borrowers who would not respond to repeated attempts to contact them or could not be located.

Borrowers who had worked with their lenders and established loan modification or formal repayment plans, and then failed to perform according to those plans, accounted for 29 percent of all foreclosures in the third quarter. The inability of borrowers to meet the terms of their repayment plans or loan modifications accounted for 40 percent of subprime ARM foreclosures, 37 percent of subprime fixed foreclosures, 17 percent of prime ARM foreclosures and 14 percent of prime fixed foreclosures. Table 8 shows that the states of Vermont, North Dakota, New Mexico and Arkansas, with little else in common, had the highest shares of foreclosures due to the inability of borrowers to live up to prior plans.

During the third quarter, mortgage servicers put in place approximately 183 thousand repayment plans and modified the rates or terms on approximately 54 thousand loans. Lenders modified approximately 13 thousand subprime ARM loans, 15 thousand subprime fixed rate loans, 4 thousand prime ARM loans and 21 thousand prime fixed-rate loans. In addition, servicers negotiated formal repayment plans with approximately 91 thousand subprime ARM borrowers, 30 thousand subprime fixed-rate borrowers, 37 thousand prime ARM borrowers and 25 thousand prime fixed-rate borrowers.

During this period the industry did approximately one thousand deed in lieu transactions and nine thousand short sales.

In an effort to put these numbers into context, Tables 9 through 13 also provide a comparison with the repayment plan and loan modification numbers. They show a breakdown of the number of foreclosures started net of those that clearly could not be helped due to reasons already discussed — investor-owned, borrower would not respond or could not be located, or borrower failed to live up to an agreement already in place. As previously discussed, the

percentages were adjusted downward to eliminate double counting for those borrowers who fell into more than one category. Therefore, while an estimated 166 thousand subprime ARM foreclosures were started during the third quarter, only 50 thousand did not fall into one of those three categories. In comparison, about 90 thousand repayment plans were renegotiated and 13 thousand loan modifications were done, for a total of 103 thousand.

Of the net 50 thousand foreclosures, many of these likely occurred due to the traditional reasons for default, loss of job, divorce, illness or excessive debt burden relative to income, not just the impact of rate resets, thus eliminating any possible benefit of a rate freeze.

1. For the purpose of this study, servicers identified "investor-owned" loans as those with a billing address different from the property address. This is a much better measure than the occupancy code the databases carry, since it is based on the declarations made by the borrower at loan closing, and we know how reliable some of those were. There would be no distinction here between a property that was never occupied by the owner and one that was occupied originally but subsequently rented.

2. The vast number of forbearances relative to modifications should give us all pause. As its name implies, forbearance is the servicer's agreement to forbear from foreclosing for a temporary, stipulated period of time, during which the borrower agrees to resume making contractual payments and make up the delinquent payments, generally in an extra monthly installment. While it is possible that a modified loan was not delinquent prior to the modification, all forbearances by definition were previously delinquent. Forbearances are faster and cheaper than modifications; servicing agreements generally give the servicer wide latitude to enter into forbearances. It is quite possible (although this issue is not addressed in the MBA report) that many forbearances are the initial stage of a modification deal: the borrower is in essence put on a "probationary" plan to catch up on payments at a temporarily reduced level, and given a permanent modification only if the borrower performs at the forbearance terms. The precise situation in which a forbearance makes sense--a borrower who occupies and is committed to homeownership and who is experiencing some temporary inability to make payments--is the precise situation in which the "Hope Now" plan makes most sense. It therefore troubles me to see no discussion of whether forbearances are being used as an initial stage of the modification process, or as a cheap, not-well-thought-out substitute that is setting repayment installments too high for borrowers to reach.

3. The data on borrowers not located or not responding merely raises the question of why that is the case. We really need to know more about this borrower group: some will be "demoralized" borrowers who simply cannot cope adequately with their distress; some will be speculators not caught with the billing address check; some will no doubt have been straw borrowers. Some will be ruthless senders of "jingle mail." But without further information, we're not able to say from this data what the best response is to this group.

Bush Calls for $145 Billion Stimulus Package

by Calculated Risk on 1/18/2008 11:50:00 AM

From AP: Bush calls for $145 billion economy plan

Apparently the proposal will be to provide tax rebates of up to $800 for individual taxpayers and $1,600 for families.