by Calculated Risk on 12/27/2015 12:18:00 PM

Sunday, December 27, 2015

Ten Economic Questions for 2016

Here is a review of the Ten Economic Questions for 2015.

There are always some international economic issues, especially with Europe, China and other areas of the world struggling. However, my focus is on the US economy, with an emphasis on housing.

Here are my ten questions for 2016. I'll follow up with some thoughts on each of these questions.

1) Economic growth: Heading into 2016, most analysts are once again pretty sanguine. Even with weak growth in the first quarter, 2015 was a decent year (GDP growth will be around 2.5% in 2015). Right now analysts are expecting growth of 2.6% in 2016, although a few analysts are projecting a recession. How much will the economy grow in 2016?

2) Employment: Through November, the economy has added 2,308,000 jobs this year, or 210,000 per month. As expected, this was down from the 260 thousand per month in 2014. Will job creation in 2016 be as strong as in 2015? Or will job creation be even stronger, like in 2014? Or will job creation slow further in 2016?

3) Unemployment Rate: The unemployment rate was at 5.0% in November, down 0.8 percentage points year-over-year. Currently the FOMC is forecasting the unemployment rate will be in the 4.6% to 4.8% range in Q4 2016. What will the unemployment rate be in December 2016?

4) Inflation: The inflation rate has increased a little recently, and some key measures are now close to the the Fed's 2% target. Will the core inflation rate rise in 2016? Will too much inflation be a concern in 2016?

5) Monetary Policy: The Fed raised rates this month, and now the question is how much will the Fed raise rates in 2016? The market is pricing in two 25 bps rate hikes in 2016, and most analysts expect three to four hikes in 2016. However, some analysts think the Fed is finished, the so-called "one and done" view. Will the Fed raise rates in 2016, and if so, by how much?

6) Real Wage Growth: Last year I was one of the most pessimistic forecasters on wage growth. That was unfortunately correct. Hopefully 2016 will be better for wages! How much will wages increase in 2016?

7) Oil Prices: The decline in oil prices was a huge story at the end of 2014, and prices have declined sharply again at the end of 2015. Will oil prices stabilize here (WTI is at $38 per barrel)? Or will prices decline further? Or will prices increase in 2016?

8) Residential Investment: Residential investment (RI) was up solidly in 2015. Note: RI is mostly investment in new single family structures, multifamily structures, home improvement and commissions on existing home sales. How much will RI increase in 2016? How about housing starts and new home sales in 2016?

9) House Prices: It appears house prices - as measured by the national repeat sales index (Case-Shiller, CoreLogic) - will be up about 5% or so in 2015 (after increasing 7% in 2012, 11% in 2013, and 5% in 2014 according to Case-Shiller). What will happen with house prices in 2016?

10) Housing Inventory: Housing inventory bottomed in early 2013. However, after increase in 2013 and 2014, inventory was down slightly year-over-year in 2015 (through November). Will inventory increase or decrease in 2016?

There are other important questions, but these are the ones I'm focused on right now.

Saturday, December 26, 2015

Schedule for Week of December 27th

by Calculated Risk on 12/26/2015 08:11:00 AM

This will be a light week for economic data.

The key report this week is Case-Shiller house prices on Tuesday.

Happy New Year!

10:30 AM: Dallas Fed Manufacturing Survey for December. This is the last of the regional manufacturing surveys for December.

9:00 AM: S&P/Case-Shiller House Price Index for October. Although this is the October report, it is really a 3 month average of August, September and October prices.

9:00 AM: S&P/Case-Shiller House Price Index for October. Although this is the October report, it is really a 3 month average of August, September and October prices.This graph shows the nominal seasonally adjusted National Index, Composite 10 and Composite 20 indexes through the September 2015 report (the Composite 20 was started in January 2000).

The consensus is for a 5.4% year-over-year increase in the Comp 20 index for October. The Zillow forecast is for the National Index to increase 4.9% year-over-year in October.

7:00 AM ET: The Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) will release the results for the mortgage purchase applications index.

10:00 AM: Pending Home Sales Index for November. The consensus is for a 0.5% increase in the index.

8:30 AM: The initial weekly unemployment claims report will be released. The consensus is for 270 thousand initial claims, up from 267 thousand the previous week.

9:45 AM: Chicago Purchasing Managers Index for December. The consensus is for a reading of 50.0, up from 48.7 in November.

All US markets will be closed for New Year's Day.

Friday, December 25, 2015

Happy Holidays!

by Calculated Risk on 12/25/2015 08:31:00 AM

Happy Holidays and Merry Christmas to All!

One of my favorite poems ...

Out through the fields and the woodsLove greatly. Enjoy the season!

And over the walls I have wended;

I have climbed the hills of view

And looked at the world, and descended;

I have come by the highway home,

And lo, it is ended.

The leaves are all dead on the ground,

Save those that the oak is keeping

To ravel them one by one

And let them go scraping and creeping

Out over the crusted snow,

When others are sleeping.

And the dead leaves lie huddled and still,

No longer blown hither and thither;

The last lone aster is gone;

The flowers of the witch-hazel wither;

The heart is still aching to seek,

But the feet question ‘Whither?’

Ah, when to the heart of man

Was it ever less than a treason

To go with the drift of things,

To yield with a grace to reason,

And bow and accept the end

Of a love or a season?

Reluctance by Robert Frost From A Boy's Will, 1913.

Thursday, December 24, 2015

Review: Ten Economic Questions for 2015

by Calculated Risk on 12/24/2015 02:01:00 PM

At the end of each year, I post Ten Economic Questions for the coming year. I followed up with a brief post on each question. The goal was to provide an overview of what I expected in 2015 (I don't have a crystal ball, but I think it helps to outline what I think will happen - and understand - and change my mind, when the outlook is wrong).

Here is a review. I've linked to my posts from the beginning of the year, with a brief excerpt and a few comments:

10) Question #10 for 2015: How much will housing inventory increase in 2015?

Right now my guess is active inventory will increase further in 2015 (inventory will decline seasonally in December and January, but I expect to see inventory up again year-over-year in 2015). I expect active inventory to move closer to 6 months supply this summer.According to the November NAR report on existing home sales, inventory was down 1.9% year-over-year in November, and the months-of-supply was at 5.1 months. Inventory could still increase in year-over-year in December, but it looks like inventory will be down slightly.

9) Question #9 for 2015: What will happen with house prices in 2015?

In 2015, inventories will probably remain low, but I expect inventories to continue to increase on a year-over-year basis. Low inventories, and a better economy (with more consumer confidence) suggests further price increases in 2015. I expect we will see prices up mid single digits (percentage) in 2015 as measured by these house price indexes.If is still early - house price data is released with a lag - but the Case Shiller data for September showed prices up 4.9% year-over-year. The year-over-year change seems to be moving mostly sideways recently in the mid single digits. As expected.

8) Question #8 for 2015: How much will Residential Investment increase?

My guess is growth of around 8% to 12% for new home sales, and about the same percentage growth for housing starts. Also I think the mix between multi-family and single family starts might shift a little more towards single family in 2015.Through November, starts were up 11% year-over-year compared to the same period in 2014. New home sales were up 14.5% year-over-year through November. About as expected.

7) Question #7 for 2015: What about oil prices in 2015?

It is impossible to predict an international supply disruption - if a significant disruption happens, then prices will obviously move higher. Continued weakness in Europe and China does seem likely - and I expect the frackers to slow down with exploration and drilling, but to continue to produce at most existing wells at current prices (WTI at $55 per barrel). This suggests in the short run (2015) that prices will stay well below $100 per barrel (perhaps in the $50 to $75 range) - and that is a positive for the US economy.WTI futures are close to $38 per barrel, so prices are lower than expected.

6) Question #6 for 2015: Will real wages increase in 2015?

As the labor market tightens, we should start seeing some wage pressure as companies have to compete more for employees. Whether real wages start to pickup in 2015 - or not until 2016 or later - is a key question. I expect to see some increase in both real and nominal wage increases this year. I doubt we will see a significant pickup, but maybe another 0.5 percentage points for both, year-over-year.Through November, nominal hourly wages were up 2.3 year-over-year .

Note: I was more pessimistic than most on wages in 2015, and that was about right.

5) Question #5 for 2015: Will the Fed raise rates in 2015? If so, when?

The FOMC will not want to immediately reverse course, so the might wait a little longer than expected. Right now my guess is the first rate hike will happen at either the June, July or September meetings.The FOMC waited until December.

4) Question #4 for 2015: Will too much inflation be a concern in 2015?

Due to the slack in the labor market (elevated unemployment rate, part time workers for economic reasons), and even with some real wage growth in 2015, I expect these measures of inflation will stay mostly at or below the Fed's target in 2015. If the unemployment rate continues to decline - and wage growth picks up - maybe inflation will be an issue in 2016.Several key measures show inflation has increased a little, and is close to the Fed's target.

So currently I think core inflation (year-over-year) will increase in 2015, but too much inflation will not be a serious concern this year.

3) Question #3 for 2015: What will the unemployment rate be in December 2015?

Depending on the estimate for the participation rate and job growth (next question), it appears the unemployment rate will decline to close to 5% by December 2015. My guess is based on the participation rate staying relatively steady in 2015 - before declining again over the next decade. If the participation rate increases a little, then I'd expect unemployment in the low-to-mid 5% range.The unemployment rate was 5.0% in November.

2) Question #2 for 2015: How many payroll jobs will be added in 2015?

Energy related construction hiring will decline in 2015, but I expect other areas of construction to be solid.Through November 2015, the economy has added 2,308,000 jobs, or 210,000 per month. This is in the expected range of 200,000 to 225,000 per month in 2015 (lower than 2014, but still solid).

As I mentioned above, in addition to layoffs in the energy sector, exporters will have a difficult year - and more companies will have difficulty finding qualified candidates. Even with the overall boost from lower oil prices - and some additional public hiring, I expect total jobs added to be lower in 2015 than in 2014.

So my forecast is for gains of about 200,000 to 225,000 payroll jobs per month in 2015. Lower than 2014, but another solid year for employment gains given current demographics.

1) Question #1 for 2015: How much will the economy grow in 2015?

Lower gasoline prices suggest an increase in personal consumption expenditures (PCE) excluding gasoline. And it seems likely PCE growth will be above 3% in 2015. Add in some more business investment, the ongoing housing recovery, some further increase in state and local government spending, and 2015 should be the best year of the recovery with GDP growth at or above 3%.Once again GDP was weaker than expected. It looks like GDP will be in the 2s again this year. Based on the November Personal Income and Outlays report, PCE growth will probably be just below 3% this year.

I missed on a few things this year: housing inventory didn't increase, the FOMC waited until December, oil prices declined more than I expected and GDP was lower than expected.

I was close on new home sales, housing starts, house prices, inflation, payroll jobs, and wages.

Black Knight's First Look at November Mortgage Data, "Fewer than 700,000 Active Foreclosures Remain"

by Calculated Risk on 12/24/2015 11:06:00 AM

From Black Knight: Black Knight Financial Services’ “First Look” at November 2015 Mortgage Data, Foreclosure Starts Hit Nine-Year Low; Fewer than 700,000 Active Foreclosures Remain

According to Black Knight's First Look report for November, the percent of loans delinquent increased 3% in November compared to October, and declined 18.3% year-over-year.

The percent of loans in the foreclosure process declined 3% in November and were down 21% over the last year.

Black Knight reported the U.S. mortgage delinquency rate (loans 30 or more days past due, but not in foreclosure) was 4.92% in November, up seasonally from 4.77% in October.

The percent of loans in the foreclosure process declined in November to 1.38%.

The number of delinquent properties, but not in foreclosure, is down 546,000 properties year-over-year, and the number of properties in the foreclosure process is down 185,000 properties year-over-year.

Black Knight will release the complete mortgage monitor for November in early January.

| Black Knight: Percent Loans Delinquent and in Foreclosure Process | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nov 2015 | Oct 2015 | Nov 2014 | Nov 2013 | |

| Delinquent | 4.92% | 4.77% | 6.03% | 6.45% |

| In Foreclosure | 1.38% | 1.43% | 1.75% | 2.54% |

| Number of properties: | ||||

| Number of properties that are delinquent, but not in foreclosure: | 2,491,000 | 2,415,000 | 3,037,000 | 3,252,000 |

| Number of properties in foreclosure pre-sale inventory: | 698,000 | 721,000 | 883,000 | 1,281,000 |

| Total Properties | 3,189,000 | 3,136,000 | 3,921,000 | 4,533,000 |

Weekly Initial Unemployment Claims decrease to 267,000

by Calculated Risk on 12/24/2015 08:34:00 AM

The DOL reported:

In the week ending December 19, the advance figure for seasonally adjusted initial claims was 267,000, a decrease of 5,000 from the previous week's revised level. The previous week's level was revised up by 1,000 from 271,000 to 272,000. The 4-week moving average was 272,500, an increase of 1,750 from the previous week's revised average. The previous week's average was revised up by 250 from 270,500 to 270,750.The previous week was revised up to 272,000.

There were no special factors impacting this week's initial claims.

The following graph shows the 4-week moving average of weekly claims since 1971.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The dashed line on the graph is the current 4-week average. The four-week average of weekly unemployment claims increased to 272,500.

This was below the consensus forecast of 270,000, and the low level of the 4-week average suggests few layoffs.

Average weekly unemployment claims in 2015 will be the lowest in over 40 years (when the workforce was much smaller).

Wednesday, December 23, 2015

Quintessential Tanta: Reflections on Alt-A (with a Donald Trump mention)

by Calculated Risk on 12/23/2015 04:42:00 PM

CR Note: Joe Weisenthal at Bloomberg Odd Lots wrote about Tanta this week (my former co-blogger): How One Woman Tried To Warn Everyone About The Housing Crash

Or as Bloomberg's Tracy Alloway tweeted: "Big Short be damned. Listen to the conversation @TheStalwart and I had with @calculatedrisk about who saw it coming"

Here is a quintessential Tanta piece that really explains mortgage lending.

And there is even a Donald Trump mention:

What is so dishonest about the association of "subprime" and "poor people" is that it simply erases the fact that a lot of rich people have terrible credit histories and a lot of poor people have never even used credit. The "classic" subprime borrower is Donald Trump as much as it is "Joe Sixpack."Tanta Vive!!!

From Doris "Tanta" Dungey, written August 8, 2008: Reflections on Alt-A

Since for media and headline purposes "Alt-A" is the new subprime--the most recent formerly-obscure mortgage lending inside-baseball term to become a part of every casual news consumer's working vocabulary--it seems like a good time to pause for some reflection on what the term might mean. Much of this exercise will be merely for archival purposes, as "Alt-A" is now pretty much officially dead as a product offering and is highly unlikely to return as "Alt-A." Eventually, after the bust works itself out and the economy leaves recession and the bankers crawl out from under their desks and stretch out those limbs that have been cramped into the fetal position, a kind of "not quite quite" lending will certainly return. I am in no way suggesting that the mortgage business has entered the Straight and Narrow Path and is going to stay on it forever because we have Learned Our Lessons. Credit cycles--not to mention institutional memories and economies like ours--don't work that way. It's just that whatever loosened lending re-emerges après le deluge will not be called "Alt-A."

Subprime will eventually come back, too. The difference is that it will come back--in some modified form--called "subprime." That term is too old, too familiar, too, well, plain to ever go away, I suspect. "Subprime" is a term invented by wonky credit analysts, not marketing departments. It is not catchy. It is not flattering nor is it euphemistic. You may console yourself if your children "have special needs" rather than "are academically below average." If you get a subprime loan, you may console yourself that you got some money from some lender, but you can't avoid the discomfort of having been labelled below-grade.

Actually, the term "B&C Lending" used to be quite popular for what we now universally refer to as "subprime." (It was also called "subprime" in those days, too. We didn't have to pick one term because nobody in the media was paying any attention to us back then and there were no blogs and even if there had been blogs if you had suggested that a blog would generate advertising revenue by talking about the nitty-gritty of the mortgage business you would have been involuntarily institutionalized.) In mortgages as in meat, "prime" meant a letter grade of A. These were the pre-FICO days, when "credit quality" was determined by fitting loans into a matrix involving a host of factors--whether you paid your bills on time, how much you owed, whether you had ever experienced a bankruptcy or a foreclosure or a collection or charge-off, etc. "B&C lending" encompassed the then-allowable range of sub-prime loans that could be made in the respectable or marginally respectable mortgage business. It was always possible to find a "D" borrower, but that was strictly in the "hard money" business: private rather than institutional lenders, interest rates that would make Vinny the Loan Shark green with envy. "F" was simply a borrower no one--not even the hard-money lenders--would lend to.

As in the academic world, of course, there was always the problem of grade inflation and too many fine distinctions. You had your "A Minus," which is actually the term Freddie Mac settled on back in the late 90s for its first foray into the higher reaches of subprime. Discussing the difference between "A Minus" and "B Plus" was just one of those otiose pastimes weary mortgage bankers got into over drinks at the hotel bar when the conversational possibilities of angels dancing on the head of a pin or whether "down payment" was one word or two had been exhausted. More or less everyone agreed that there wasn't but a tiny smidgen of difference between the two, except that "A Minus" sounded better. Same with the term "near prime," which wasn't uncommon but never became as popular as "A Minus." "Near prime" is also "near subprime." "A Minus" completed the illusion that it was nearer the A than the B, even if the distances involved were sometimes hard to see with the naked eye.

But all of that grading and labelling was still basically limited to considerations of the credit quality of the borrower, understood to mean the borrower's past history of handing debt. Residential mortgage lending never, of course, limited itself to considering creditworthiness; we always had "Three C's": creditworthiness, capacity, and collateral. "Capacity" meant establishing that the borrower had sufficient current income or other assets to carry the debt payments. "Collateral" meant establishing that the house was worth at least the loan amount--that it fully secured the debt. It was universally considered that these three things, the C's, were analytically and practically separable.

That, I think, is very hard for people today to understand. The major accomplishment of last five to eight years, mortgage-lendingwise, has been to entirely erase the C distinctions and in fact to mostly conflate them. For the last couple of years, for instance, you would routinely read in the papers that "subprime" meant loans made to low-income people. Or it meant loans made to people who couldn't make a down payment or who borrowed more than the value of their property--that is, whose loans were very likely to be under-collateralized. This kind of characterization of subprime always struck us old-timer insiders as bizarre, but it seems to have made sense to the rest of the world and it stuck. After all, the media didn't really care about or even notice this thing called "subprime" until it began to be obvious that it was going to end really really badly. It therefore seemed perfectly obvious to a lot of folks that it must primarily involve poor people who borrow too much.

Those of us who were there at the time tend to remember this differently. In the old model of the Three C's, a loan had to meet minimum requirements for each C in order to get made. We didn't do two out of three. The only lenders who ever did one out of three were precisely those "hard money" lenders, who cared only about the value of the collateral. This was because they mostly planned on repossessing it. Institutional lenders' business plan still involved making your money by getting paid back in dollars for the loans you made, not by taking title to real estate and selling it.

The difference between a prime and a subprime lender was simply how low you set the bar for one of the C's, creditworthiness. Unless you were a hard-money lender, you expected to be paid back, so you never lowered the bar on capacity: everybody had to have some source of cash flow to make loan payments with. Traditional institutional subprime mortgage lenders were even more anal-compulsive about collateral than prime lenders were, a fact that probably surprises most people. Until very recently, historically speaking, institutional subprime lending involved very low LTVs and probably the lowest rate of appraisal fraud or foolishness in the business.

That isn't so surprising if you think about the concept of "risk layering," which is also an industry term. In days gone by, with the three C's, you didn't "layer" risk. If the creditworthiness grade was less than "A," then the capacity grade and the collateral grade had to be "summa cum laude" in order to balance the loan risk. It wasn't until well into the bubble years that anybody seriously put forth the idea that you could make a loan that got a "B" on credit and a "B" on capacity and a "B" on collateral and expect not to lose money.

Of course there has always been a connection between creditworthiness and capacity. Most Americans will pay back their debts as agreed unless they experience a loss of income. People rack up "B&C" credit histories most commonly after they have been laid off, fired, disabled, divorced, or just generally lost income. But this was true at any original income level: upper-middle-class people can lose income and become "B&C" credits. Lower-income folks may well be most vulnerable to income loss--first fired, first "globalized"--but then lower-income folks until recently had smaller debts to pay back out of reduced income, too. What is so dishonest about the association of "subprime" and "poor people" is that it simply erases the fact that a lot of rich people have terrible credit histories and a lot of poor people have never even used credit. The "classic" subprime borrower is Donald Trump as much as it is "Joe Sixpack."

Traditional subprime lending was what you might think of as "recovery" lending. That is, while the borrower's past credit problems were due to some interruption in income or catastrophic loss of cash assets with which to service existing debts, the subprime lenders didn't enter your picture until you had re-established some income. If you want to know what a "D" or "F" borrower was, it was basically someone still in the financial crisis--still unemployed, still underemployed, still unable to work. "B" and "C" borrowers had resumed income, but they still had a fresh pile of bad things on their credit reports--charge-offs, collections, bankruptcies. Prime lenders wouldn't make loans to these borrowers because even though they had resumed capacity, their recent credit history was too poor. Prime lenders want to you "re-establish" your credit history as well as your income, which pretty much means that those nasty credit events have to be several years old, on average, without recurrence in the most recent years, before you can be an "A" again. Absent subprime lenders, that means going without credit for those years.

This is where the idea came from--much promoted by subprime lenders during the boom--that subprime loans were intended to be fairly short-term kinds of financing that helped a borrower "re-establish" his or her creditworthiness. The whole rationale for the famous 2/28 ARM was that after two years of good payment history on that loan, the borrower could refinance into a prime loan and thus never have to pay the "exploding" interest rate at reset. (If you didn't keep up with the payments in the first two years, you were thus "still subprime" and deserved to pay that higher rate.) That was a perfectly fine rationale as long as subprime lenders used rational capacity and collateral requirements--reasonable DTIs during the early years of the loan, low LTVs--to make those loans. When all the "risk layering" started, it was less and less plausible that these borrowers would ever "become prime" in two years by making on-time mortgage payments, and what we got was a class of permanent subprime borrowers who survived by serial refinancing, each time into a lower "grade" loan product, until the final step of foreclosure.

You're probably still wondering what all this has to do with Alt-A. Alt-A is sort of a weird mirror-image of subprime lending. If subprime was traditionally about borrowers with good capacity and collateral but bad credit history, Alt-A was about borrowers with a good credit history but pretty iffy capacity and collateral. That is to say, while subprime makes some amount of sense, Alt-A never made any sense. It is a child of the bubble.

"Classic" subprime lending worked because, while it always charged borrowers a higher interest rate, it found a way to restructure payments such that the borrower's overall prospects for making regular payments improved. A classic "C" loan, for instance, was also called a "pre-foreclosure takeout." The borrower had had a period of reduced or no income, got seriously behind on her mortgage payment, and was facing loss of the house. Even though income had resumed, it wasn't enough to make up the arrearage while also making currently-due payments. So the subprime lender would refinance the loan, rolling the arrearage into the new loan amount, and offset the higher rate and larger balance with a longer term or some kind of "ramping up" structure. The "ramp-up," by the way, was not, historically, mostly by using ARMs. There were all kinds of old-fashioned exotic mortgages that you don't hear about any more, like the Graduated Payment Mortgage and the Step Loan and the Wraparound Mortgage and so on, all of which involved some way of starting off loans with a lower payment that slowly racheted up over three to five years or so into a fully-amortizing payment. It certainly wasn't always successful, but its intent was exactly to enable people to catch up on an arrearage and then actually begin to retire debt.

Alt-A, we are regularly told, is a kind of loan for people with good credit but weak capacity or collateral. It overwhelmingly involved the kind of "affordability product" like ARMs and interest only and negative amortization and 40-year or 50-year terms that "ramps" payment streams. But it doesn't do this in order to help anyone "catch up" on arrearages; people with good credit don't have any arrearages. Alt-A was and has always been about maximizing consumption, whether of housing or of all the other consumer goods you can spend "MEW" on. If subprime was supposed to be about taking a bad-credit borrower and working him back into a good-credit borrower, Alt-A was about taking a good-credit borrower and loading him up with enough debt to make him eventually subprime.

The utter fraudulence of the whole idea of Alt-A involves the suggestion that people who have managed debt in the past that was offered to them in the past on conservative "prime" terms must therefore be capable of managing debt in the future that is offered to them on lax terms. FICOs or traditional credit analyses are good predictors of future credit performance, but only if the usual terms of credit-granting are similar in the past and in the future. Think of it this way: subprime borrowers had proven that they couldn't carry 50 pounds, so the subprime lenders found a way to restructure their debts so that they were only carrying 40. Alt-A lenders took a lot of people who had proven they could carry 50 pounds and used that fact to justify adding another 50 pounds to the burden.

This has not worked out well.

The "Alt" in Alt-A is short for "alternative." Alt-A is one of the purest examples of a "new paradigm" thingy you can find. The conceit of Alt-A is that there is another way to approach "prime" lending that is equivalent in risk (assuming risk-based pricing) but--amazing!--way more painless. Toss out verifications of income and assets, and you are no longer evaluating capacity. Toss out down payments and careful formal appraisals and analysis of sales contracts and you are no longer evaluating collateral. But lookit that FICO!

A lot of folks see the failure of Alt-A as a failure of FICO scores. I don't see it that way. FICO scoring is just an automated and much more consistent way of measuring past credit history than sitting around with a ten-page credit report counting up late payments and calculating balance-to-limit ratios and subtracting for collection accounts and all that tedious stuff underwriters used to do with a pencil and legal pad. I have seen no compelling evidence that FICO scoring is any less reliable than the old-fashioned way of "scoring" credit history.

To me, the failure of Alt-A is the failure to represent reality of the view that people who have a track record of successfully managing modest amounts of debt will therefore do fine with very high amounts of debt. Obviously the whole thing was ultimately built on the assumption that house prices would rise forever and there would always be another refi. There was also the assumption that people are emotionally attached to their FICO scores--in more old-fashioned terms, that borrowers care about their "reputation" and don't want to ruin it by defaulting on a loan. The trouble with that assumption was that we were busy building a credit industry in which there was plentiful credit--on easy terms--for people with any FICO, any "reputation." A bad credit history is only a strong deterrent to default when credit is rationed, granted only to those with acceptable reputations, or--as in the case of "classic" subprime--granted only to those with poor reputations but strong capacity and collateral, and at a penalty rate. Unfortunately, the consumer focus (encouraged, of course, by the industry) on monthly payment rather than actual cost of credit meant that for a lot of people the fact of the "penalty rate" just didn't register. In such an environment, the fear of losing your good credit record isn't much of a deterrent to default.

I should point out that besides the "stated income" and no-down junk, the other big segment of the Alt-A pool was "nonstandard" collateral types. One of the biggies in that category were what insiders call "non-warrantable condos." (The warranties in question are the ones the GSEs force you to make when you sell a condo loan; in essence a non-warrantable condo means one the GSEs won't accept.) What was wrong with these condos? Not enough pre-sales. Not enough sales to owner-occupants rather than investors. Inadequately funded HOAs with absurd budgets. Big blocks of units owned by a single entity or individual. In other words, speculator bait. This kind of thing isn't an "alternative" to "A." It is commercial or margin lending masquerading as long-term residential mortgage lending. It may well be "prime" commercial lending. It just isn't residential mortgage lending.

Part of the terrible results of Alt-A lending is that this book took on risks that historically were taken only on the commercial side, where the rates were higher, the cash-flow analysis was better, and the LTVs a lot lower. (Not that commercial real estate lending didn't also have its dumb credit bubble, too.) The thing is, as long as the flipping of speculative purchases worked--and it did for several years--it worked. Meaning, those Alt-A loans prepaid quite quickly with no losses. That masked the reality of Alt-A--that it was largely a way for people to take on more debt than they ever had before--for quite some time.

Of course we all know now--I happen to think a lot of us knew then--that Alt-A is chock-full o' fraud. My point is that even without excessive "stated income" or appraisal fraud, the Alt-A model was essentially doomed. "Alt-A" is the kind of lending you would only do after a real estate bust, not during a real estate boom--that is, when housing costs and thus debt levels are dropping, not rising. Unfortunately, we're going to have a hard time using something like Alt-A to stimulate our way into recovery once the housing market has actually bottomed out, because Alt-A is too implicated in the bust. I don't think anyone is going to be allowed to get away with moving all that REO off their books by making loans on easy terms to someone who managed to maintain a good FICO during the bust, even though that might actually make some sense.

One of the main reasons we are in a mortgage credit crunch is that two possible models of "recovery" lending--subprime and Alt-A--got used up blowing the bubble. I think it will be a long time before lending standards ease significantly, and I think subprime will come back first. But I do suspect we've seen the last of Alt-A for a much longer time.

Philly Fed: State Coincident Indexes increased in 40 states in November

by Calculated Risk on 12/23/2015 02:42:00 PM

From the Philly Fed:

The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia has released the coincident indexes for the 50 states for November 2015. In the past month, the indexes increased in 40 states, decreased in five, and remained stable in five, for a one-month diffusion index of 70. Over the past three months, the indexes increased in 44 states, decreased in five, and remained stable in one, for a three-month diffusion index of 78.Note: These are coincident indexes constructed from state employment data. An explanation from the Philly Fed:

The coincident indexes combine four state-level indicators to summarize current economic conditions in a single statistic. The four state-level variables in each coincident index are nonfarm payroll employment, average hours worked in manufacturing, the unemployment rate, and wage and salary disbursements deflated by the consumer price index (U.S. city average). The trend for each state’s index is set to the trend of its gross domestic product (GDP), so long-term growth in the state’s index matches long-term growth in its GDP.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This is a graph is of the number of states with one month increasing activity according to the Philly Fed. This graph includes states with minor increases (the Philly Fed lists as unchanged).

In November, 44 states had increasing activity (including minor increases).

Five states have seen declines over the last 6 months, in order they are North Dakota (worst), Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Louisiana - mostly due to the decline in oil prices.

Here is a map of the three month change in the Philly Fed state coincident indicators. This map was all red during the worst of the recession, and is mostly green now.

Here is a map of the three month change in the Philly Fed state coincident indicators. This map was all red during the worst of the recession, and is mostly green now. Source: Philly Fed.

Comments on November New Home Sales

by Calculated Risk on 12/23/2015 11:50:00 AM

The new home sales report for October was somewhat below expectations, and sales for August, September and October were revised down. Sales were up 9.1% year-over-year in November (SA).

Earlier: New Home Sales increased to 490,000 Annual Rate in November.

Even though the November report was somewhat disappointing, sales are still up solidly year-to-date. The Census Bureau reported that new home sales this year, through November, were 461,000, not seasonally adjusted (NSA). That is up 14.5% from 402,000 sales during the same period of 2014 (NSA). That is a strong year-over-year gain for 2015 through November.

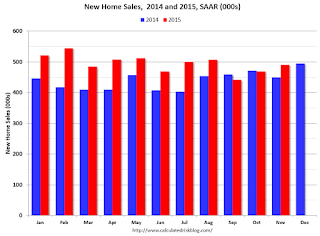

This graph shows new home sales for 2014 and 2015 by month (Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate).

The year-over-year gains were stronger earlier this year, but the overall year-over-year gain should be solid in 2015. The comparisons in early 2016 will be more difficult.

Overall this was a solid year for new home sales.

And here is another update to the "distressing gap" graph that I first started posting a number of years ago to show the emerging gap caused by distressed sales. Now I'm looking for the gap to close over the next few years.

Following the housing bubble and bust, the "distressing gap" appeared mostly because of distressed sales.

I expect existing home sales to move more sideways, and I expect this gap to slowly close, mostly from an increase in new home sales.

However, this assumes that the builders will offer some smaller, less expensive homes.

Note: Existing home sales are counted when transactions are closed, and new home sales are counted when contracts are signed. So the timing of sales is different.

New Home Sales increased to 490,000 Annual Rate in November

by Calculated Risk on 12/23/2015 10:00:00 AM

The Census Bureau reports New Home Sales in November were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of 490 thousand.

The previous three months were revised down by a total of 36 thousand (SAAR).

"Sales of new single-family houses in November 2015 were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 490,000, according to estimates released jointly today by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. This is 4.3 percent above the revised October rate of 470,000 and is 9.1 percent above the November 2014 estimate of 449,000"

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The first graph shows New Home Sales vs. recessions since 1963. The dashed line is the current sales rate.

Even with the increase in sales since the bottom, new home sales are still fairly low historically.

The second graph shows New Home Months of Supply.

The months of supply decreased in November to 5.7 months.

The months of supply decreased in November to 5.7 months. The all time record was 12.1 months of supply in January 2009.

This is now in the normal range (less than 6 months supply is normal).

"The seasonally adjusted estimate of new houses for sale at the end of November was 232,000. This represents a supply of 5.7 months at the current sales rate."

On inventory, according to the Census Bureau:

On inventory, according to the Census Bureau: "A house is considered for sale when a permit to build has been issued in permit-issuing places or work has begun on the footings or foundation in nonpermit areas and a sales contract has not been signed nor a deposit accepted."Starting in 1973 the Census Bureau broke this down into three categories: Not Started, Under Construction, and Completed.

The third graph shows the three categories of inventory starting in 1973.

The inventory of completed homes for sale is still low, and the combined total of completed and under construction is also low.

The last graph shows sales NSA (monthly sales, not seasonally adjusted annual rate).

The last graph shows sales NSA (monthly sales, not seasonally adjusted annual rate).In November 2015 (red column), 34 thousand new homes were sold (NSA). Last year 31 thousand homes were sold in November.

The all time high for November was 86 thousand in 2005, and the all time low for November was 20 thousand in 2010.

This was below expectations of 503,000 sales SAAR in November, and prior months were revised down - a somewhat disappointing report. I'll have more later today.