by Calculated Risk on 8/26/2019 08:44:00 AM

Monday, August 26, 2019

Chicago Fed "Index points to slower economic growth in July"

From the Chicago Fed: Index points to slower economic growth in July

Led by declines in production-related indicators, the Chicago Fed National Activity Index (CFNAI) fell to –0.36 in July from +0.03 in June. All four broad categories of indicators that make up the index decreased from June, and all four categories made negative contributions to the index in July. The index’s three-month moving average, CFNAI-MA3, moved up to –0.14 in July from –0.30 in June.This graph shows the Chicago Fed National Activity Index (three month moving average) since 1967.

emphasis added

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This suggests economic activity was below the historical trend in July (using the three-month average).

According to the Chicago Fed:

The index is a weighted average of 85 indicators of growth in national economic activity drawn from four broad categories of data: 1) production and income; 2) employment, unemployment, and hours; 3) personal consumption and housing; and 4) sales, orders, and inventories.

...

A zero value for the monthly index has been associated with the national economy expanding at its historical trend (average) rate of growth; negative values with below-average growth (in standard deviation units); and positive values with above-average growth.

Sunday, August 25, 2019

Sunday Night Futures

by Calculated Risk on 8/25/2019 08:48:00 PM

Weekend:

• Schedule for Week of August 25, 2019

Monday:

• At 8:30 AM ET, Chicago Fed National Activity Index for July. This is a composite index of other data.

• Also at 8:30 AM, Durable Goods Orders for July from the Census Bureau. The consensus is for a 1.1% increase in durable goods orders.

• At 10:30 AM, Dallas Fed Survey of Manufacturing Activity for August.

From CNBC: Pre-Market Data and Bloomberg futures: S&P 500 are down 14 and DOW futures are down 143 (fair value).

Oil prices were up over the last week with WTI futures at $53.22 per barrel and Brent at $58.53 barrel. A year ago, WTI was at $70, and Brent was at $74 - so oil prices are down about 20% year-over-year.

Here is a graph from Gasbuddy.com for nationwide gasoline prices. Nationally prices are at $2.58 per gallon. A year ago prices were at $2.83 per gallon, so gasoline prices are down 25 cents year-over-year.

Hotels: Occupancy Rate Decreased Year-over-year

by Calculated Risk on 8/25/2019 12:52:00 PM

From HotelNewsNow.com: STR: US hotel results for week ending 17 August

The U.S. hotel industry reported mostly negative year-over-year results in the three key performance metrics during the week of 11-17 August 2019, according to data from STR.The following graph shows the seasonal pattern for the hotel occupancy rate using the four week average.

In comparison with the week of 12-18 August 2018, the industry recorded the following:

• Occupancy: -1.0% to 71.7%

• Average daily rate (ADR): +0.4% to US$130.89

• Revenue per available room (RevPAR): -0.6% at US$93.90

emphasis added

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The red line is for 2019, dash light blue is 2018 (record year), blue is the median, and black is for 2009 (the worst year probably since the Great Depression for hotels).

Occupancy has been solid in 2019, close to-date compared to the previous 4 years - but has been a little soft YoY in recent weeks.

Seasonally, the occupancy rate will now start to decline as the peak summer travel season ends.

Data Source: STR, Courtesy of HotelNewsNow.com

Saturday, August 24, 2019

Schedule for Week of August 25, 2019

by Calculated Risk on 8/24/2019 08:11:00 AM

The key report this week is second estimate of Q2 GDP.

Other key reports include Personal Income and Outlays for July and Case-Shiller house prices for June.

For manufacturing, the August Richmond and Dallas Fed surveys will be released.

8:30 AM ET: Chicago Fed National Activity Index for July. This is a composite index of other data.

8:30 AM: Durable Goods Orders for July from the Census Bureau. The consensus is for a 1.1% increase in durable goods orders.

10:30 AM: Dallas Fed Survey of Manufacturing Activity for August.

9:00 AM: S&P/Case-Shiller House Price Index for June.

9:00 AM: S&P/Case-Shiller House Price Index for June.This graph shows the year-over-year change in the seasonally adjusted National Index, Composite 10 and Composite 20 indexes through the most recent report (the Composite 20 was started in January 2000).

The consensus is for a 2.3% year-over-year increase in the Comp 20 index for June.

9:00 AM: FHFA House Price Index for May 2019. This was originally a GSE only repeat sales, however there is also an expanded index.

10:00 AM: Richmond Fed Survey of Manufacturing Activity for August. This is the last of the regional surveys for August.

7:00 AM ET: The Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) will release the results for the mortgage purchase applications index.

8:30 AM: Gross Domestic Product, 2nd quarter 2019 (second estimate). The consensus is that real GDP increased 2.0% annualized in Q2, down from the advance estimate of 2.1% in Q2.

8:30 AM: The initial weekly unemployment claims report will be released. The consensus is for 213 thousand initial claims, up from 209 thousand last week.

10:00 AM: Pending Home Sales Index for July. The consensus is for a 0.3% decrease in the index.

8:30 AM ET: Personal Income and Outlays, July 2019. The consensus is for a 0.3% increase in personal income, and for a 0.5% increase in personal spending. And for the Core PCE price index to increase 0.2%.

9:45 AM: Chicago Purchasing Managers Index for August.

10:00 AM: University of Michigan's Consumer sentiment index (Final for August). The consensus is for a reading of 92.3.

Friday, August 23, 2019

Lawler: Updated “Demographic” Outlook Using Recent Population Estimates by Age

by Calculated Risk on 8/23/2019 04:00:00 PM

From housing economist Tom Lawler: Updated “Demographic” Outlook Using Recent Population Estimates by Age

Executive Summary: Analysts who use intermediate or long term population projections to forecast key economic variables such as labor force growth, household growth, etc. should recognize that the latest official Census intermediate and long term population projections (produced in 2017 and referred to as “Census 2017”) are out of date. Specifically, Census 2017 materially over-predicted births, materially under-predicted deaths (mainly for non-elderly adults), and somewhat over-predicted net international migration (NIM) for each of the last several years. In addition, the assumptions in Census 2017 projections over the next several years (and more) are almost certainly too high for births, too low for deaths, and too high for NIM. As a result, population growth, household growth, and labor force growth over the next few years will be lower than forecasts based on the Census 2017 population projections. How much lower depends critically on net international migration, which in the current environment is a big unknown.

Using more realistic assumptions on births and deaths by age, I have developed updated population projections by age through 2021 assuming (1) net international migration in each year is the same as in 2018; and (2) there is no international migration in 2020 or 2021. I did the latter scenario to highlight the importance of net international migration assumptions on population projections.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Earlier this year the Census Bureau released its latest (“Vintage 2018) estimates of the US resident population by single year of age for July 1, 2018, as well as for July of each of the previous 8 years. These latest estimates give analysts a new starting point that can be used to update population projections by age using assumptions about births, deaths by age, and net international migration by age. These population projections are key inputs into forecasts of other key economic variables such as the labor force and US households.

While many analysts prefer to use “official” Census population projections in forecasting other key economic variables, there are several reasons why this is often not a good idea. First, official Census population projections are only released every couple of years, and may be out of date. And second, such projections may have assumptions about the key drivers of population growth that may not be viewed as “reasonable.”

The latest official Census population projections were done in late 2017 and released to the public in early 2018. The “starting point” for these projections was the “Vintage 2016” population estimates, and population estimates for 2016 have since been revised. In addition, current estimates of births, deaths, and net international migration from 2016 to 2018 are significantly different from the “Census 2017” projections. And finally, the assumptions in the “Census 2017” projections for the key drivers of population changes, especially death rates by age, are not realistic or consistent with recent actual death rates by age.

The latest estimate of the US resident population on July 1, 2018 was 327,167,434, which is 724,477 lower than the Census 2017 projection for that date. Fewer births, more deaths, and lower international migration all contributed to the projection shortfall. Below is a table showing the differences between the latest July 1 2018 population estimate and the July 1, 2018 forecast from the Census 2017 projection by key component.

| Census 2017 Projections | Vintage 2018 Estimates | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7/1/2016 | 323,127,513 | 323,071,342 | (56,171) |

| Births: 7/1/2016 - 6/30/2018 | 8,129,169 | 7,757,482 | (371,687) |

| Deaths: 7/1/2016 - 6/30/2018 | 5,363,099 | 5,593,449 | 230,350 |

| Net Int'l Migration: 7/1/2016 - 6/30/2018 | 1,998,328 | 1,932,059 | (66,269) |

| 7/1/2018 | 327,891,911 | 327,167,434 | (724,477) |

Births from 7/1/2016 to 6/30/2018 were significantly below projected levels from Census 2017. In addition, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) recently estimated that US births in 2018 (calendar year) totaled just 3,788,235, the lowest annual number of births in 32 years, and a whopping 306,730 below the Census 2017 projection for the 12 month period ending June 2019.

Deaths from 7/1/2016 to 6/30/2018 were significantly above projected levels from Census 2017. While the Census Bureau did not release estimates of deaths (or net international migration) by age in its “Vintage 2018” release, Census does use data from the NCHS on deaths by age, and these data indicate that most of the higher than projected deaths from Census 2017 were in the 20-74 year old age groups.

The Census 2017 population projections were based on a dated “death rate” table, as well as on projections that death rates for most age groups would decline each year. In fact, however, death rates for many age groups have increased over the past few years. The assumptions on deaths from Census 2017 over the next several years are almost certainly way too low, especially for the 20-74 year old age groups.

Finally the latest Census estimates of net international migration (NIM) from 7/1/2016 to 6/30/2018 are somewhat below the Census 2017 projections. Moreover, updated estimates for NIM (which are, unfortunately, subject to considerable error) suggest a materially different age distribution than that assumed in the Census 2017 projections.

Below is a table comparing the latest Census estimates of the US resident population for 2018 with the projections from Census 2017 for 2018 by 5-year ago groups.

| US Resident Population, 7/1/2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vintage 2018 Estimate | Census 2017 Projection | Difference | |

| Total | 327,167,434 | 327,891,911 | -724,477 |

| 0-4 | 19,810,275 | 20,172,617 | -362,342 |

| 5-9 | 20,195,642 | 20,166,270 | 29,372 |

| 10-14 | 20,879,527 | 20,866,300 | 13,227 |

| 15-19 | 21,097,221 | 21,084,451 | 12,770 |

| 20-24 | 21,873,579 | 21,966,919 | -93,340 |

| 25-29 | 23,561,756 | 23,601,976 | -40,220 |

| 30-34 | 22,136,018 | 22,125,395 | 10,623 |

| 35-39 | 21,563,587 | 21,556,772 | 6,815 |

| 40-44 | 19,714,301 | 19,728,816 | -14,515 |

| 45-49 | 20,747,135 | 20,786,395 | -39,260 |

| 50-54 | 20,884,564 | 20,923,227 | -38,663 |

| 55-59 | 21,940,985 | 22,012,901 | -71,916 |

| 60-64 | 20,331,651 | 20,408,221 | -76,570 |

| 65-69 | 17,086,893 | 17,127,778 | -40,885 |

| 70-74 | 13,405,423 | 13,418,850 | -13,427 |

| 75-79 | 9,267,066 | 9,274,592 | -7,526 |

| 80-84 | 6,127,308 | 6,131,125 | -3,817 |

| 85+ | 6,544,503 | 6,539,306 | 5,197 |

As the table shows, there are significant differences between the “Vintage 2018” population estimates and the projections from Census 2017, not just in the total but also in the age distribution.

In “Vintage 2018” Census also provided updated population projections for 2019, which are used (among other things) as “controls” for the household employment estimates for 2019. Below is a table comparing the Vintage 2018 population projections for 2019 with the Census 2017 projections for 2019.

| Resident Population Projections for 7/1/2019 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vintage 2018 | Census 2017 | Difference | |

| Total | 329,158,518 | 330,268,840 | -1,110,322 |

| 0-4 | 19,702,853 | 20,304,120 | -601,267 |

| 5-9 | 20,222,613 | 20,180,503 | 42,110 |

| 10-14 | 20,829,999 | 20,814,198 | 15,801 |

| 15-19 | 21,114,493 | 21,100,800 | 13,693 |

| 20-24 | 21,744,207 | 21,861,558 | -117,351 |

| 25-29 | 23,612,082 | 23,693,302 | -81,220 |

| 30-34 | 22,510,095 | 22,522,671 | -12,576 |

| 35-39 | 21,798,813 | 21,798,185 | 628 |

| 40-44 | 19,979,623 | 20,003,487 | -23,864 |

| 45-49 | 20,443,042 | 20,491,118 | -48,076 |

| 50-54 | 20,515,438 | 20,559,577 | -44,139 |

| 55-59 | 21,912,472 | 22,001,226 | -88,754 |

| 60-64 | 20,608,057 | 20,712,610 | -104,553 |

| 65-69 | 17,487,028 | 17,543,604 | -56,576 |

| 70-74 | 14,060,332 | 14,076,777 | -16,445 |

| 75-79 | 9,678,247 | 9,685,598 | -7,351 |

| 80-84 | 6,327,181 | 6,329,092 | -1,911 |

| 85+ | 6,611,943 | 6,590,414 | 21,529 |

(Note: The Vintage 2018 projection for 2019 appears to have assumed the same number as births as for 2018, though recent data suggest that births were lower.)

If analysts had used the Census 2017 population projections to forecast the US labor force and the number of US households, and had been accurate in their forecasts of labor force participation rates and headship rates, they would have over-predicted the size of the labor force in mid-2019 by about 400,000, and over-predicted the number of households in mid-2019 by about 260,000.

Obviously, Census 2017 population projections have not tracked recent estimates and projections very well. In addition, Census 2017 assumptions for births, deaths, and net international migration are likely to be considerable off from likely “actuals” for the years ahead.

For analysts who use intermediate and long term population projections to forecast other key economic or social variables such as household growth, labor force growth, social security/medicare enrollment/payments, college enrollment, etc., it seems clear that it would not be appropriate to use the Census 2017 population projections. However, these are the latest “official” projections that have been released, and many analysts prefer to use “official” projections. Moreover, formulating one’s own population projections by age requires one to make assumptions not just on total births, deaths, and NIM, but also deaths and NIM by single year of age, and there aren’t timely publicly-released data on either of the latter.

To help some of these analysts, I have, using some unpublished data on recent trends, produced US resident population projections through 2021 using the following assumptions:

1. Annual births from 2019 through 2021 are the same as those in calendar year 2018 (3,788,235);

2. Deaths rates by age are similar to those in 2018 (though somewhat lower for age groups that saw a sizable increase over the last few years); and

3. Net International Migration by age is the same each year as the Census estimates for 2018.

Note that the biggest “wild card” in assumptions is NIM; not only are recent estimates subject to much higher uncertainty than the other two key drivers of population growth, but it is also virtually impossible in the current political environment to make a reasonable projection for NIM. For example, recent actions by the Administration set to take effect in mid-October would, if implemented, have a significantly negative impact on immigration over the next few years.

I also have produced population projections by age assuming no international migration (this is not necessarily the same as no immigration, as a lot of people leave the country for abroad each year). I did this to highlight the importance of NIM on the outlook for the population.

Note that I did not use the Vintage 2018 projections for 2019, but instead used the assumptions discussed above.

These alternative projections are shown on the next page for select age groups.

| US Resident Population: Alternative Projections | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census 2017 Projections | ||||

| 7/1/2018 | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2020 | 7/1/2021 | |

| Total | 327,891,911 | 330,268,840 | 332,639,102 | 334,998,398 |

| 0-14 | 61,205,187 | 61,298,821 | 61,408,926 | 61,510,603 |

| 15-24 | 43,051,370 | 42,962,358 | 42,937,831 | 43,004,867 |

| 25-34 | 45,727,371 | 46,215,973 | 46,491,403 | 46,716,390 |

| 35-44 | 41,285,588 | 41,801,672 | 42,351,795 | 43,006,437 |

| 45-54 | 41,709,622 | 41,050,695 | 40,615,037 | 40,324,022 |

| 55-64 | 42,421,122 | 42,713,836 | 42,782,544 | 42,593,657 |

| 65-74 | 30,546,628 | 31,620,381 | 32,789,437 | 33,953,050 |

| 75+ | 21,945,023 | 22,605,104 | 23,262,129 | 23,889,372 |

| Flat Births, More Realistic Death Rates, Flat NIM | ||||

| 7/1/2018 | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2020 | 7/1/2021 | |

| Total | 327,167,434 | 329,072,705 | 330,917,403 | 332,700,753 |

| 0-14 | 60,885,444 | 60,698,571 | 60,507,167 | 60,290,588 |

| 15-24 | 42,970,800 | 42,861,557 | 42,822,738 | 42,882,730 |

| 25-34 | 45,697,774 | 46,128,836 | 46,337,496 | 46,484,660 |

| 35-44 | 41,277,888 | 41,786,370 | 42,323,937 | 42,961,919 |

| 45-54 | 41,631,699 | 40,958,397 | 40,507,001 | 40,198,337 |

| 55-64 | 42,272,636 | 42,516,252 | 42,534,068 | 42,293,993 |

| 65-74 | 30,492,316 | 31,537,868 | 32,667,883 | 33,780,930 |

| 75+ | 21,938,877 | 22,584,854 | 23,217,113 | 23,807,596 |

| Flat Births, More Realistic Death Rates, No International Migration | ||||

| 7/1/2018 | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2020 | 7/1/2021 | |

| Total | 327,167,434 | 329,072,705 | 329,940,031 | 330,747,524 |

| 0-14 | 60,885,444 | 60,698,571 | 60,284,355 | 59,860,569 |

| 15-24 | 42,970,800 | 42,861,557 | 42,537,458 | 42,330,317 |

| 25-34 | 45,697,774 | 46,128,836 | 46,069,155 | 45,934,117 |

| 35-44 | 41,277,888 | 41,786,370 | 42,209,180 | 42,720,399 |

| 45-54 | 41,631,699 | 40,958,397 | 40,468,714 | 40,117,461 |

| 55-64 | 42,272,636 | 42,516,252 | 42,507,588 | 42,241,276 |

| 65-74 | 30,492,316 | 31,537,868 | 32,649,225 | 33,742,244 |

| 75+ | 21,938,877 | 22,584,854 | 23,214,356 | 23,801,141 |

Below are tables showing the differences between the latter two scenarios and the Census 2017 population projections.

| Alternate Population Projections vs. Census 2017 Projections | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat Births, More Realistic Death Rates, Flat NIM | ||||

| Total | -724,477 | -1,196,135 | -1,721,699 | -2,297,645 |

| 0-14 | -319,743 | -600,250 | -901,759 | -1,220,015 |

| 15-24 | -80,570 | -100,801 | -115,093 | -122,137 |

| 25-34 | -29,597 | -87,137 | -153,907 | -231,730 |

| 35-44 | -7,700 | -15,302 | -27,858 | -44,518 |

| 45-54 | -77,923 | -92,298 | -108,036 | -125,685 |

| 55-64 | -148,486 | -197,584 | -248,476 | -299,664 |

| 65-74 | -54,312 | -82,513 | -121,554 | -172,120 |

| 75+ | -6,146 | -20,250 | -45,016 | -81,776 |

| Flat Births, More Realistic Death Rates, No International Migration | ||||

| 7/1/2018 | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2020 | 7/1/2021 | |

| Total | -724,477 | -1,196,135 | -2,699,071 | -4,250,874 |

| 0-14 | -319,743 | -600,250 | -1,124,571 | -1,650,034 |

| 15-24 | -80,570 | -100,801 | -400,373 | -674,550 |

| 25-34 | -29,597 | -87,137 | -422,248 | -782,273 |

| 35-44 | -7,700 | -15,302 | -142,615 | -286,038 |

| 45-54 | -77,923 | -92,298 | -146,323 | -206,561 |

| 55-64 | -148,486 | -197,584 | -274,956 | -352,381 |

| 65-74 | -54,312 | -82,513 | -140,212 | -210,806 |

| 75+ | -6,146 | -20,250 | -47,773 | -88,231 |

Obviously, the outlook for population growth, labor force growth, household formations, and other economic variables over the next few years depends critically on one’s assumptions about net international migration. The “flat births/flat NIM” scenario is probably a “high” forecast, given, recent Trump administration actions/policies, while the “no international migration” scenario is more designed to show what population growth would look like without international migration. In the “flat births/flat NIM” scenarios growth in the labor force over the next two years would be about 0.1% lower per year than forecasts based on Census 2017, while household growth would be about 120,000 lower per year. In the no international migration scenario labor force growth over the next two years would be 0.4% lower per year, and household growth would be about 370,000 per year lower per year, than Census 2017-based forecasts.

A few Comments on July New Home Sales

by Calculated Risk on 8/23/2019 11:58:00 AM

New home sales for July were reported at 635,000 on a seasonally adjusted annual rate basis (SAAR). Sales for the previous three months were revised up, combined.

Sales for June were revised up to a new cycle high.

Annual sales in 2019 should be the best year for new home sales since 2007.

Earlier: New Home Sales decreased to 635,000 Annual Rate in July, Sales in June revised up to New Cycle High.

This graph shows new home sales for 2018 and 2019 by month (Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate).

Sales in July were up 4.3% year-over-year compared to July 2018.

Year-to-date (through July), sales are up 4.1% compared to the same period in 2018.

The second half comparisons will be easier, so sales should be higher in 2019 than in 2018.

And here is another update to the "distressing gap" graph that I first started posting a number of years ago to show the emerging gap caused by distressed sales.

Following the housing bubble and bust, the "distressing gap" appeared mostly because of distressed sales.

Even though distressed sales are down significantly, following the bust, new home builders focused on more expensive homes - so the gap has only closed slowly.

I still expect this gap to close. However, this assumes that the builders will offer some smaller, less expensive homes.

Note: Existing home sales are counted when transactions are closed, and new home sales are counted when contracts are signed. So the timing of sales is different.

Q3 GDP Forecasts: Around 2%

by Calculated Risk on 8/23/2019 11:46:00 AM

From Merrill Lynch:

We continue to track 2.1% qoq saar for 3Q. 2Q GDP growth is likely to be revised modestly lower in the second release to 1.8% from the advance estimate of 2.1%. [Aug 23 estimate]From the NY Fed Nowcasting Report

emphasis added

The New York Fed Staff Nowcast stands at 1.8% for 2019:Q3. [Aug 23 estimate].And from the Altanta Fed: GDPNow

The GDPNow model estimate for real GDP growth (seasonally adjusted annual rate) in the third quarter of 2019 is 2.2 percent on August 16, unchanged from August 15 after rounding. [Aug 16 estimate] (next update on Aug 26th)CR Note: These early estimates suggest real GDP growth will be around 2% annualized in Q3.

Fed Chair Powell: "Challenges for Monetary Policy"

by Calculated Risk on 8/23/2019 10:25:00 AM

From Fed Chair Powell: Challenges for Monetary Policy A few excerpts:

Through the FOMC's setting of the federal funds rate target range and our communications about the likely path forward for policy and the economy, we seek to influence broader financial conditions to promote maximum employment and price stability. In forming judgments about the appropriate stance of policy, the Committee digests a broad range of data and other information to assess the current state of the economy, the most likely outlook for the future, and meaningful risks to that outlook. Because the most important effects of monetary policy are felt with uncertain lags of a year or more, the Committee must attempt to look through what may be passing developments and focus on things that seem likely to affect the outlook over time or that pose a material risk of doing so. Risk management enters our decision making because of both the uncertainty about the effects of recent developments and the uncertainty we face regarding structural aspects of the economy, including the natural rate of unemployment and the neutral rate of interest. It will at times be appropriate for us to tilt policy one way or the other because of prominent risks. Finally, we have a responsibility to explain what we are doing and why we are doing it so the American people and their elected representatives in Congress can provide oversight and hold us accountable.

We have much experience in addressing typical macroeconomic developments under this framework. But fitting trade policy uncertainty into this framework is a new challenge. Setting trade policy is the business of Congress and the Administration, not that of the Fed. Our assignment is to use monetary policy to foster our statutory goals. In principle, anything that affects the outlook for employment and inflation could also affect the appropriate stance of monetary policy, and that could include uncertainty about trade policy. There are, however, no recent precedents to guide any policy response to the current situation. Moreover, while monetary policy is a powerful tool that works to support consumer spending, business investment, and public confidence, it cannot provide a settled rulebook for international trade. We can, however, try to look through what may be passing events, focus on how trade developments are affecting the outlook, and adjust policy to promote our objectives.

This approach is illustrated by the way incoming data have shaped the likely path of policy this year. The outlook for the U.S. economy since the start of the year has continued to be a favorable one. Business investment and manufacturing have weakened, but solid job growth and rising wages have been driving robust consumption and supporting moderate growth overall.

As the year has progressed, we have been monitoring three factors that are weighing on this favorable outlook: slowing global growth, trade policy uncertainty, and muted inflation. The global growth outlook has been deteriorating since the middle of last year. Trade policy uncertainty seems to be playing a role in the global slowdown and in weak manufacturing and capital spending in the United States. Inflation fell below our objective at the start of the year. It appears to be moving back up closer to our symmetric 2 percent objective, but there are concerns about a more prolonged shortfall.

Committee participants have generally reacted to these developments and the risks they pose by shifting down their projections of the appropriate federal funds rate path. Along with July's rate cut, the shifts in the anticipated path of policy have eased financial conditions and help explain why the outlook for inflation and employment remains largely favorable.

Turning to the current context, we are carefully watching developments as we assess their implications for the U.S. outlook and the path of monetary policy. The three weeks since our July FOMC meeting have been eventful, beginning with the announcement of new tariffs on imports from China. We have seen further evidence of a global slowdown, notably in Germany and China. Geopolitical events have been much in the news, including the growing possibility of a hard Brexit, rising tensions in Hong Kong, and the dissolution of the Italian government. Financial markets have reacted strongly to this complex, turbulent picture. Equity markets have been volatile. Long-term bond rates around the world have moved down sharply to near post-crisis lows. Meanwhile, the U.S. economy has continued to perform well overall, driven by consumer spending. Job creation has slowed from last year's pace but is still above overall labor force growth. Inflation seems to be moving up closer to 2 percent. Based on our assessment of the implications of these developments, we will act as appropriate to sustain the expansion, with a strong labor market and inflation near its symmetric 2 percent objective.

emphasis added

New Home Sales decreased to 635,000 Annual Rate in July, Sales in June revised up to New Cycle High

by Calculated Risk on 8/23/2019 10:15:00 AM

The Census Bureau reports New Home Sales in July were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of 635 thousand.

The previous three months were revised up combined. June was revised up to a new cycle high.

"Sales of new single‐family houses in July 2019 were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 635,000, according to estimates released jointly today by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. This is 12.8 percent below the revised June rate of 728,000, but is 4.3 percent above the July 2018 estimate of 609,000."

emphasis added

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The first graph shows New Home Sales vs. recessions since 1963. The dashed line is the current sales rate.

Even with the increase in sales over the last several years, new home sales are still somewhat low historically.

The second graph shows New Home Months of Supply.

The months of supply increased in July to 6.4 months from 5.5 months in June.

The months of supply increased in July to 6.4 months from 5.5 months in June. The all time record was 12.1 months of supply in January 2009.

This is at the top of the normal range (less than 6 months supply is normal).

"The seasonally‐adjusted estimate of new houses for sale at the end of July was 337,000. This represents a supply of 6.4 months at the current sales rate."

On inventory, according to the Census Bureau:

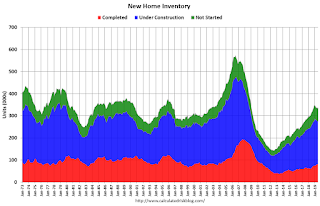

On inventory, according to the Census Bureau: "A house is considered for sale when a permit to build has been issued in permit-issuing places or work has begun on the footings or foundation in nonpermit areas and a sales contract has not been signed nor a deposit accepted."Starting in 1973 the Census Bureau broke this down into three categories: Not Started, Under Construction, and Completed.

The third graph shows the three categories of inventory starting in 1973.

The inventory of completed homes for sale is still somewhat low, and the combined total of completed and under construction is close to normal.

The last graph shows sales NSA (monthly sales, not seasonally adjusted annual rate).

The last graph shows sales NSA (monthly sales, not seasonally adjusted annual rate).In July 2019 (red column), 53 thousand new homes were sold (NSA). Last year, 52 thousand homes were sold in July.

The all time high for July was 117 thousand in 2005, and the all time low for July was 26 thousand in 2010.

This was slightly below expectations of 645 thousand sales SAAR, however sales in the three previous months were revised up, combined. I'll have more later today.

Thursday, August 22, 2019

Friday: New Home Sales, Fed Chair Powell

by Calculated Risk on 8/22/2019 06:18:00 PM

Friday:

• At 10:00 AM ET, New Home Sales for July from the Census Bureau. The consensus is for 645 thousand SAAR, down from 646 thousand in June.

• Also at 10:00 AM, Speech, Fed Chair Jerome Powell, Challenges for Monetary Policy, At the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium: Challenges for Monetary Policy, Jackson Hole, Wyo.