by Calculated Risk on 6/22/2009 10:18:00 PM

Monday, June 22, 2009

For Returning Visitors: A Few Posts from the Missing Days

Note: For visitors of many Google hosted blogs, the redirect feature from a blogspot address to a custom URL failed for six days (from late Tuesday June 16th until Monday afternoon June 22nd). This is now resolved. Welcome back! I apologize for any inconvenience.

Here are a few posts and links that might interest you:

“I am not particularly of the green shoots group yet,” [General Electric Co. Vice Chairman John] Rice said ... “I have not seen it in our order patterns yet. At the macro level, there may be statistics suggesting the economy is starting to turn. I am not seeing it yet. ... We are preparing for 12 or 18 months of tough sledding.”

Once again, welcome back!

"A number of banks" Suspend TARP Dividends

by Calculated Risk on 6/22/2009 08:00:00 PM

From the WSJ: Three Banks Suspend Their TARP Dividends (ht jb)

Treasury spokeswoman Meg Reilly said Monday that "a number of banks" that got taxpayer-funded capital under TARP are no longer paying dividends to the government.The article mentions three banks by name: Pacific Capital Bancorp, of Santa Barbara, Seacoast Banking Corp. of Florida, of Stuart, and Midwest Banc Holdings Inc., of Melrose Park, Ill.

...

"Here the government has given the banks money at great terms, but the fact that they can't keep up with it is worrisome," said Michael Shemi, an investor at New York hedge-fund firm Christofferson, Robb & Co. "It tells you of the deep problems of community and regional banks."

These banks received the funds in December.

Note: missing up to six dividend payments was allowed under the TARP agreement, so this isn't a default.

CRE: Chicago Eyesore

by Calculated Risk on 6/22/2009 06:00:00 PM

Michael sent me this photo of the halted Waterview Tower project in Chicago.

Michael sent me this photo of the halted Waterview Tower project in Chicago.

Click on image for larger graph in new window.

Photo Credit: Michael C.

The development was halted at 26 stories - the plan was for a 90 story building with a combination of condos and a hotel.

Every CRE bust leaves what Crain's Chicago Business calls the Waterview: "a 26-story concrete monument symbolizing the excesses of the real estate boom" ... here are couple of recent stories on the Waterview.

From Crain's Chicago Business: Waterview Hotel project on the market

CB Richard Ellis Inc. is taking on one of the toughest jobs in today’s languishing downtown real estate market: finding a buyer for the stalled Waterview Tower and Shangri-La Hotel project on Wacker Drive.And from the Chicago Sun-Times: City wants high-rise crane removed

...

The developer is tangling in court with the Bank of America, which is trying to collect on a $20-million loan, and construction firms that claim they’re owed a combined $85 million.

Impatient about the stillborn construction site on Wacker Drive, city officials are demanding the removal of the high-rise crane at the proposed Waterview Tower. No work has been done on the planned 90-story building since last year, and now it stands as a shell about 27 stories tall at the southwest corner of Wacker and Clark.Another CRE eyesore.

A spokesman for the city's Buildings Department said it is worried that an unused crane can pose a safety hazard.

White House Expects 10% Unemployment Soon, and Stock Market

by Calculated Risk on 6/22/2009 04:00:00 PM

The AP reports that White House spokesman Robert Gibbs says Obama expects "10 percent unemployment within the next few months".

By popular demand ... Click on graph for larger image in new window.

Click on graph for larger image in new window.

The first graph shows the S&P 500 since 1990.

The dashed line is the closing price today.

The S&P 500 is up almost 32% from the bottom (235 points), and still off almost 43% from the peak (672 points below the max). The second graph is from Doug Short of dshort.com (financial planner): "Four Bad Bears".

Note that the Great Depression crash is based on the DOW; the three others are for the S&P 500.

Moody's: CRE Prices Fall 8.6% in April

by Calculated Risk on 6/22/2009 02:17:00 PM

From Dow Jones: Commercial Real-Estate Prices Fall 8.6% On Month In April

Commercial real-estate prices fell 8.6% in April ... which leaves prices down one-quarter from a year earlier ...Prices in the CRE market are not as sticky as the residential market, so prices fall much quicker. We've seen plenty of half off sales for distressed CRE, and this report suggests the average decline is about 25% over the last year.

"The size of April's decline, following a 5.5% decline in January, also suggests that sellers are beginning to capitulate to the realities of commercial real-estate markets," says Moody's Managing Director Nick Levidy. ...

Harvard on Housing 2005

by Calculated Risk on 6/22/2009 01:17:00 PM

Just so you know ... I used to make fun of the Harvard reports.

Here is the Harvard State of the Nation's Housing 2005 report (ht curious)

The unprecedented length and strength of the boom has, however, fanned fears that the rate of construction far exceeds long run demand. Although averaging more than 1.9 million units annually since 2000, housing starts and manufactured home placements appear to be roughly in line with household demand. As evidence, the inventory of new homes for sale relative to the pace of home sales is near its lowest level ever. Given this small backlog, new home sales would have to retreat by more than a third—and stay there for a year or more—to create anywhere near a buyer’s market.There were plenty of warnings and caveats in the 2005 report (covers through 2004), but for the most part they missed the housing bubble and the coming crash.

Moreover, the US mortgage finance system is now well integrated into global capital markets and offers an ever-growing array of products. This gives borrowers more flexibility to shift to loans tied to lower adjustable rates in the event of an interest-rate rise. Although adjustable loans do increase the risk of payment shock at the end of the fixed-rate period, borrowers are increasingly choosing hybrid loans that allow them to lock in favorable rates for several years.

With homes appreciating so rapidly over the last few years, there is concern that house price bubbles have formed in many markets. Clearly, ratios of house prices to median household incomes are up sharply and now stand at a 25-year high in more than half of evaluated metro areas.

...

Whether the hottest housing markets are now headed for a sharp correction is another question. The current economic recovery may give house prices in these locations the room to cool down rather than crash if higher interest rates slow the sizzling pace

of house price appreciation. Moreover, in several metropolitan areas where house prices have appreciated the fastest, natural or regulatory-driven supply constraints may have resulted in permanently higher prices.

...

For now, though, house prices should keep rising as long as job and income growth continue to offset the recent jump in short term interest rates. House prices would come under greater pressure, however, if the economy stumbles and jobs are lost.

And from the 2006 report (covers 2005):

[T]he housing sector continues to benefit from solid job and household growth, recovering rental markets, and strong home price appreciation. As long as these positive forces remain in place, the current slowdown should be moderate.

Over the longer term, household growth is expected to accelerate from about 12.6 million over the past ten years to 14.6 million over the next ten. When combined with projected income gains and a rising tide of wealth, strengthening demand should lift housing production and investment to new highs.

...

Fortunately, most homeowners have sizable equity stakes to protect them from selling at a loss even if they find themselves unable to make their mortgage payments. As measured in 2004—before the latest house price surge—only three percent of owners had equity of less than five percent, and fully 87 percent had a cushion of at least 20 percent.

...

The greatest threat to housing markets is a precipitous drop in house prices. Fortunately, sharp price declines of five percent or more seldom occur in the absence of severe overbuilding, dramatic employment losses, or a combination of the two. The fact that these conditions did not exist and that interest rates were so low explains why the housing boom was able to continue without interruption when the recession hit in 2001. With building levels still in check and the economy expanding, large house price declines appear unlikely for now.

...

Despite the current cool-down, the long-term outlook for housing is bright. New Joint Center for Housing Studies projections—reflecting more realistic, although arguably still conservative, estimates about future immigration—put household growth in the next decade fully 2.0 million above the 12.6 million of the past decade. On the strength of this growth alone, housing production should set new records.

Harvard: 2009 State of the Nation’s Housing Report

by Calculated Risk on 6/22/2009 12:29:00 PM

“The best that can be said of the market is that house price corrections and steep cuts in housing production are creating the conditions that will lead to an eventual recovery. For now, markets remain under considerable stress.”

Eric S. Belsky, Executive Director of the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

From Jeff Collins at the O.C. Register: Harvard: Housing recovery yet to emerge

The U.S. housing market will rebound eventually, according to a Harvard University report. Demographics and underbuilding are conspiring to up demand and revive home prices.Jeff has more. I think this graphic is informative:

But that day still is a long way off, perhaps not until sometime after 2010, the university’s Joint Center for Housing Studies said in its 2009 State of the Nation’s Housing report

...

•Read the press release: HERE!

•Read the fact sheet: HERE!

•Read the report: HERE!

Click on image for larger graph in new window.

Click on image for larger graph in new window.This shows that the worst mortgages were the private label securities (as an example mortgages originated by New Century, and securitized by Bear Stearns).

The Housing Wealth Effect?

by Calculated Risk on 6/22/2009 09:39:00 AM

Here we go again on this hotly debated topic: How much do changes in house prices impact consumption?

Charles W. Calomiris of Columbia University, Stanley D. Longhofer of the Barton School of Business and William Miles of Wichita State University argue at the WSJ Real Time Economics blog that the wealth effect of housing has been overstated: The (Mythical?) Housing Wealth Effect

...[M]any still fear that lower home values will depress consumer spending. This “wealth effect,” a drop in home values that causes consumers to cut back on purchases, is thought to dampen economic growth and hamper any recovery.I haven't read their paper (update: I have a copy).

At first glance, it seems reasonable to expect such a wealth effect. If consumers are less wealthy because of declines in the value of the assets they own, whether they be stocks or their homes — it seems logical that they would cut back on their spending. Indeed, many prominent economists have conducted research purporting to find large housing wealth effects, and often argue that the wealth effect from homes exceeds that from equities. Moreover, the Federal Reserve employs a model, which presumably guides its policies, that assumes the housing wealth effect is large.

A more careful look at the data, guided by economic theory, however, suggests that much of this evidence has been misinterpreted and that the reaction of consumption to housing wealth changes is probably very small. ... an increase in house prices raises the value of the typical homeowner’s asset, but such a price increase is also an equivalent increase in the cost of providing oneself housing consumption. In the aggregate, changes in house prices will have offsetting effects on value gain and costs of housing services, and leave nothing left over to spend on non-housing consumption.

Up to this point, we have neglected the question of whether housing wealth change affects consumption through another, indirect channel — a financing channel — by affecting consumers’ access to credit.

[CR note: this is MEW or the Home ATM]

... Some observers point to the latest housing boom, and the increased use of HELOCS and other mortgages during the boom, as evidence that housing prices spurred consumption through this financing channel. While this indirect financing channel is a theoretical possibility, it is an empirical question whether it is significant in its effect, and even if the indirect financial effect is present it should not produce a “first-order” effect of housing wealth on consumption; housing wealth should still matter much less for consumption than other forms of wealth.

... We put the data through numerous robustness checks, and found in most model specifications housing wealth had zero effect on consumption. In those few cases where housing wealth did have an impact on consumer spending, the impact was always smaller in magnitude than that from stock wealth, contrary to Case, Quigley and Shiller’s findings. We conclude that the impact of housing wealth on consumption, if it exists at all, is much smaller than popularly feared.

There are two parts here: 1) how do changes in house prices affect consumption, and 2) how does access to the Home ATM effect consumption. On the second point, I think the answer is MEW had a significant impact on consumption ... I frequently heard from auto, RV, boat, motorcycle, and home accessory retailers that their customers were borrowing from their homes during the boom to buy these products. All of these areas have seen sharp declines in consumption as MEW had declined.

This severe decline in consumption was easy to predict - and it happened. Meanwhile these authors dismiss it as simply "a theoretical possibility".

However, on the key point, I think most of the decline in consumption related to declining MEW is behind us.

Here is a recent paper on Mortgage Equity Withdrawal (MEW): House Prices, Home Equity-Based Borrowing, and the U.S. Household Leverage Crisis by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi (both University of Chicago Booth School of Business and NBER) (ht Jan Hatzius)

From the authors abstract (the entire paper is available at the link):

Using individual-level data on homeowner debt and defaults from 1997 to 2008, we show that borrowing against the increase in home equity by existing homeowners is responsible for a significant fraction of both the sharp rise in U.S. household leverage from 2002 to 2006 and the increase in defaults from 2006 to 2008. Employing land topology-based housing supply elasticity as an instrument for house price growth, we estimate that the average homeowner extracts 25 to 30 cents for every dollar increase in home equity. Money extracted from increased home equity is not used to purchase new real estate or pay down high credit card debt, which suggests that consumption is a likely use of borrowed funds. Home equity-based borrowing is stronger for younger households, households with low credit scores, and households with high initial credit card utilization rates. Homeowners in high house price appreciation areas experience a relative decline in default rates from 2002 to 2006 as they borrow heavily against their home equity, but experience very high default rates from 2006 to 2008. Our estimates suggest that home equity based borrowing is equal to 2.3% of GDP every year from 2002 to 2006, and accounts for over 20% of new defaults in the last two years.A couple of key points:

emphasis added

And here are the Kennedy-Greenspan estimates (NSA - not seasonally adjusted) of home equity extraction through Q4 2008, provided by Jim Kennedy based on the mortgage system presented in "Estimates of Home Mortgage Originations, Repayments, and Debt On One-to-Four-Family Residences," Alan Greenspan and James Kennedy, Federal Reserve Board FEDS working paper no. 2005-41.

This graph shows what Dr. Kennedy calls "active MEW" (Mortgage Equity Withdrawal). This is defined as "Gross cash out" plus the change in the balance of "Home equity loans".

This graph shows what Dr. Kennedy calls "active MEW" (Mortgage Equity Withdrawal). This is defined as "Gross cash out" plus the change in the balance of "Home equity loans".This measure has fallen close to zero, and is an estimate of the impact of MEW on consumption. I believe that when people refinance with cash out or draw down HELOCs, they usually spend the money.

Instead of focusing on the wealth effect from house prices, I think the more important channel for consumption was home equity extraction.

Problematic Foreclosure Data

by Calculated Risk on 6/22/2009 08:37:00 AM

From the Atlanta Journal-Constitution: Foreclosure numbers don’t add up (ht Mark)

When the most frequently quoted source of foreclosure information released its April statistics, it estimated that 3,746 properties in metro Atlanta’s five core counties had been slapped with foreclosure sale notices.It is very frustrating trying to find reliable foreclosure data. I use a series from DataQuick in California (for Notice of Defaults) that goes back to the early '90s. But that is just one state, and just one step in the foreclosure process and doesn't tell us how many NODs are cured. Very frustrating.

But a review of local legal advertisements – the only official source of Georgia foreclosure information – suggested a decidedly different number for April, with 7,462 properties slated for auction on the courthouse steps.

What’s the right number? That’s a surprisingly difficult question to answer.

At a time when an explosion in the number of distressed mortgage loans has emerged as the most pressing economic issue in decades, there is no official government source for foreclosure statistics.

...

RealtyTrac has faced questions for months about the reliability of its numbers.

An AJC review of the company’s data in 2007 prompted RealtyTrac to admit serious inaccuracies in Georgia. The company reported a 75 percent increase in foreclosures from June 2007 to July 2007, but later admitted errors and said the filings actually increased by 14 percent.

...

Some economists believe it’s time for the federal government to produce its own foreclosure statistics. And experts say many are kicking around ways to make that happen.

“Ideally we would have a national database of mortgage transactions,” said [Dan Immergluck, a Georgia Tech professor].

World Bank: Recovery to be "Subdued"

by Calculated Risk on 6/22/2009 12:52:00 AM

From Bloomberg: World Bank Cuts Forecast for Global Economy, Developing Nations

The world economy is forecast to contract 2.9 percent this year, compared with a prior estimate of a 1.7 percent decline, the Washington-based lender said in a report released today. Global growth will return next year with a 2 percent expansion, the bank said, cutting its forecast from a 2.3 percent prediction about three months ago.They say "subdued", I say "sluggish".

...

“While the global economy is projected to begin expanding once again in the second half of 2009, the recovery is expected to be much more subdued than might normally be the case,” the report said. “Unemployment is on the rise, and poverty is set to increase in developing economies, bringing with it a substantial deterioration in conditions for the world’s poor.”

You like potato and I like potahto,

You like tomato and I like tomahto;

Potato, potahto, tomato, tomahto!

Let's call the whole thing off!

George and Ira Gershwin, Let's Call the Whole Thing Off

Sunday, June 21, 2009

FedCASH: "No Credit Needed"

by Calculated Risk on 6/21/2009 11:10:00 PM

Click on photo for larger image in new window.

Click on photo for larger image in new window.

Photo Credit: Rander (thanks!)

Up to $2500 today!

No Credit Needed!

We Say Yes!

This photo is in Bedford, TX.

Interesting - "FedCash" appears to be a registered trade mark of the Fed.

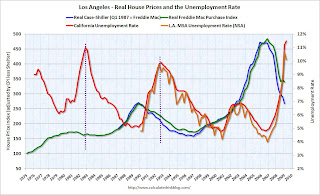

LA, NY, San Francisco, Boston, Seattle, Detroit: Real Prices and the Unemployment Rate

by Calculated Risk on 6/21/2009 07:32:00 PM

Yesterday I posted a comparison of national real house prices and the unemployment rate. Today I'm posting the comparison for various cities.

Previous posts in this series:

National Real House prices and the unemployment rate.

Washington, D.C. real prices and unemployment.

Miami, Chicago, Dallas: Real House Prices and Unemployment Rate

Notes: House prices are from Case-Shiller (back to 1987) and Freddie Mac's Purchase index (back to 1975). The Case-Shiller index was set equal to the Freddie Mac index in the first quarter Case-Shiller is available for each city, and then both indexes adjusted by CPI less shelter for each region.

The red unemployment rate is for each state and goes back to 1976. The orange unemployment line is for the metropolitan statistical areas (MSA) (most go back to 1990)

Note the scale of unemployment rate doesn't start at zero (to better compare to house prices) and scales are different for each city. Click on image for larger graph in new window.

Click on image for larger graph in new window.

The first graph is for Los Angeles and shows the well known late '80s housing bubble.

There was a much smaller price bubble in the late '70s.

This is a good example of house prices still falling in real terms after a housing bubble, until sometime after the unemployment rate peaks. The second graph is for San Francisco.

The second graph is for San Francisco.

San Francisco had a similar bubble as LA. The purple lines show the peaks in the unemployment rate after a house price bubble.

And the third graph is for New York. New York had a bubble in the late '80s too.

New York had a bubble in the late '80s too.

And just like in LA and SF, real house prices continued to fall even after the unemployment rate peaked.

New York didn't have a bubble in the late '70s. The fourth graph is for Boston.

The fourth graph is for Boston.

Boston had a serious housing bubble in the mid-to-late '80s - in some ways this was the worst of the late '80s housing bubbles.

Once again (sorry no line), real prices continued to drift downwards for a few years after the post-bubble unemployment rate had peaked in the '90s. The fifth graph is for Seattle.

The fifth graph is for Seattle.

Seattle has a changing economy - back in the '70s it was driven by the fortunes of Boeing, but by the '90s, it was more Microsoft and other tech companies and that shift probably kept house prices from falling in the early '90s.

For the late '70s bubble, we see house prices fell until the unemployment rate peaked (see dashed purple line). And finally Detroit (note the price index is on a different scale).

And finally Detroit (note the price index is on a different scale).

Detroit had a mini-bubble in the late '70s, and once again real prices fell, until the post bubble unemployment rate peaked.

Although there are many other factors influencing house prices, I expect real house prices to decline until the unemployment rate peaks - and maybe even decline slightly (in real terms) for a few more years.

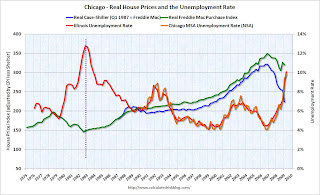

Miami, Chicago, Dallas: Real House Prices and Unemployment Rate

by Calculated Risk on 6/21/2009 03:42:00 PM

Yesterday I posted a comparison of national real house prices and the unemployment rate. Today I'm posting the comparison for various cities.

Previous posts:

National Real House prices and the unemployment rate.

Washington, D.C. real prices and unemployment.

Notes: House prices are from Case-Shiller (back to 1987 for Miami and Chicago, and 2000 for Dallas) and Freddie Mac's Purchase index (back to 1975). The Case-Shiller index was set equal to the Freddie Mac index in Q1 1987 (Q 2000 for Dallas), and then both indexes adjusted by CPI less shelter for South Urban cities (Chicago used Midwest urban cities).

The red unemployment rate is for the states and only goes back to 1976. The orange unemployment line is for the metropolitan statistical areas (MSA)

Note the scale of unemployment rate doesn't start at zero (to better compare to house prices). Click on image for larger graph in new window.

Click on image for larger graph in new window.

In Miami, real house prices increased in the last '70s, but those increases were dwarfed by the current bubble.

Miami doesn't have a good example of a previous bubble to compare falling house prices and the unemployment rate.

Maybe if we had data back to the great Florida housing bubble of the 1920s! The second graph is for Chicago.

The second graph is for Chicago.

Chicago has an example of a previous housing bubble in the late '70s. And house prices fell basically until the unemployment rate peaked (see dashed purple line).

And the third graph is for Dallas.

Dallas had a housing price bubble in the early '80s because of high oil prices during that period. House prices and the unemployment rate appear unrelated, and we would probably have to look at net migration to understand why prices fell.

House prices and the unemployment rate appear unrelated, and we would probably have to look at net migration to understand why prices fell.

The pattern I expect is for house prices to fall (after a bubble) until the unemployment rate peaks - and possibly for some time after the unemployment rate peaks.

Some serious bubble cities to come ...

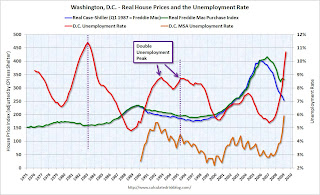

House Prices and the Unemployment Rate, Washington D.C.

by Calculated Risk on 6/21/2009 12:28:00 PM

Yesterday I posted a comparison of house prices and the unemployment rate on a national (U.S.) basis.

I'm working on a series of graphs for individual cities. Each graph takes some work and a few assumptions (I will outline the assumptions for each city).

Notes: House prices are from Case-Shiller (back to 1987) and Freddie Mac's Purchase index (back to 1975). The Case-Shiller index was set equal to the Freddie Mac index in Q1 1987, and then both indexes adjusted by CPI less shelter for North Urban cities.

The red unemployment rate is for Wash, D.C. (as statewide) and only goes back to 1976. Update: the orange is for D.C. MSA  Click on image for larger graph in new window.

Click on image for larger graph in new window.

Washington D.C. participated in the late '80s housing bubble, and only somewhat in the late '70s bubble. The dashed purple lines line up the peak unemployment rate - following the housing bubbles - with house prices.

Note the scale of unemployment rate doesn't start at zero (to better compare to house prices).

It appears real house prices declined until the unemployment rate peaked, and then remained stagnant for a few years. Following the late 1980s housing bubble (with a double unemployment peak in D.C.), house prices declined for a few years after the unemployment rate peaked for a 2nd time.

Although there are periods when there is no relationship between the unemployment rate and house prices, this graph suggests that house prices will not bottom (in real terms) until the unemployment rate peaks (or later, especially since the current bubble dwarfs those previous housing bubbles).

More to come ...

Record Bonuses on tap for Goldman Staff

by Calculated Risk on 6/21/2009 09:56:00 AM

From The Observer: Goldman to make record bonus payout (ht Jonathan)

Goldman Sachs staff can look forward to the biggest bonus payouts in the firm's 140-year history after a spectacular first half of the year ... Staff in London were briefed last week on the banking and securities company's prospects and told they could look forward to bumper bonuses if, as predicted, it completed its most profitable year ever.Usually I don't post on compensation issues, but record bonuses in a recession is pretty amazing.

...

In April, Goldman said it would set aside half of its £1.2bn first-quarter profit to reward staff, much of it in bonuses. It is believed to have paid 973 bankers $1m or more last year, while this year's payouts are on track to be the highest for most of the bank's 28,000 staff, including about 5,400 in London.

The Onion: US To Trade Gold Reserves For Cash

by Calculated Risk on 6/21/2009 12:14:00 AM

HT John. Enjoy ...

Saturday, June 20, 2009

NY Times: Treasury and Bill Gross

by Calculated Risk on 6/20/2009 08:59:00 PM

From the NY Times: Treasury’s Got Bill Gross on Speed Dial

[Bill Gross'] mood brightens when he talks about how much money Pimco could reap by participating in the Geithner [PPIP] plan. No wonder: the terms are deliciously favorable for participants selected as fund managers. Money managers like Pimco would be expected to raise at least $500 million from their clients. The Treasury would match that with taxpayer dollars. Then Pimco and the Treasury would create a jointly owned fund of at least $1 billion that would buy distressed mortgage bonds.These low interest rate, non-recourse loans allow money managers to overpay for bank assets; essentially gambling with the taxpayers money. No wonder this makes Bill Gross salivate. The banks are winners. The money managers are winners (if a few of the gambles pay off). And the taxpayers are the losers.

Government largess doesn’t stop there. The fund will be eligible for low-interest financing from both the Treasury and the Fed that analysts at Credit Suisse First Boston estimate could be as high as four times the total equity in the fund. So if Pimco ponied up $500 million, the fund that it manages could borrow $4 billion.

Pimco would then negotiate with banks to buy their wobbly mortgage-backed securities. Mr. Gross says that some of these securities pay an interest rate as high as 14 percent and that even if default rates were 70 percent, Pimco and the government would still make a 5 percent return after covering their negligible borrowing costs. That means the government-Pimco partnership could make at least $250 million in a year on a $5 billion investment fund. Of that amount, Pimco would get $125 million — a 25 percent return on its original investment.

But here’s the part that makes Mr. Gross salivate. If things go badly, the government is responsible for repaying all that debt.

Also, the article mentions Bill Gross and yoga:

Mr. Gross, 65, has long been celebrated for his eccentricities. He learned some of his lucrative investing strategies by gambling in Las Vegas. Many of his most inspired ideas arrived while he was standing on his head doing yoga.I've attended the same yoga class as Mr. Gross a few times - hence Tanta's joke in this post: BONG HiTS 4 BILL GROSS!

Near the end of 2007, I was waiting for a yoga class, and some random guy walked up to Gross and asked him if it was time to buy distressed bonds (think Bear Stearns). Gross said "probably"! I almost said something, but then I realized maybe Gross didn't like that guy ... or didn't like being asked about bonds at a yoga class.

House Prices and the Unemployment Rate

by Calculated Risk on 6/20/2009 05:00:00 PM

We've discussed supply and demand, price-to-income and price-to-rent ratios, and real house prices, in trying to forecast how long house prices will continue to decline.

This is a comparison of real house prices and the unemployment rate.

Note: House prices are national from Case-Shiller (back to 1987) and Freddie Mac's Purchase index (back to 1970). The Case-Shiller index was set equal to the Freddie Mac index in Q1 1987, and then both indexes adjusted by CPI less shelter. Click on image for larger graph in new window.

Click on image for larger graph in new window.

The two previous national housing bubbles (late 1970s and late 1980s) are shown on the graph. The dashed purple lines line up the peak unemployment rate - following the housing bubbles - with house prices.

It appears real house prices declined until the unemployment rate peaked, and then remained stagnant for a few years. Following the late 1980s housing bubble, the Case-Shiller index suggests prices declined for a few years after the unemployment rate peaked.

Although there are periods when there is no relationship between the unemployment rate and house prices, this graph suggests that house prices will not bottom (in real terms) until the unemployment rate peaks (or later, especially since the current bubble dwarfs those previous housing bubbles). And it is unlikely that the unemployment rate will peak for some time ...

I'll post some similar graphs for a few Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA) later, comparing local house prices with the local unemployment rate.

Popular Google Product Suffers Major Disruption

by Calculated Risk on 6/20/2009 02:55:00 PM

UPDATED: Service disruption resolved on Monday June 22nd.

For visitors of many Google hosted blogs, the redirect feature from a blogspot address to a custom URL failed for six days (from late Tuesday June 16th until Monday afternoon June 22nd).

Original post:

The popular Google (GOOG) blogging product, blogger.com, has suffered a major service disruption. The disruption was first reported on Tuesday, June 16th, and is ongoing now resolved (June 22nd update).

This is impacting many blogs hosted on blogger.com, including popular blogs like Americablog.com, eschatonblog.com, and the economics blog calculatedriskblog.com.

Blogger.com offers a feature to redirect users from a blogspot URL to a custom domain name. As an example, atrios.blogspot.com is supposed to be automatically redirected to eschatonblog.com. However, starting last Tuesday, the Google product started inserting an interstitial page before redirecting.

For Firefox uses this appears as a redirect warning notifying users that they were leaving Blogger. For Internet Explorer and Safari users (and iPhone users), they are notified that the page could not be displayed or that the blogs no longer exist.

Users are still able to access the blogs via the custom domain name, however any bookmarks, or links from other sites, using the blogspot address are affected.

This has led to a significant decline in traffic for many Blogspot.com hosted blogs, with some sites reporting a 50 percent decline in traffic.

Blogger engineers acknowledged the problem on Wednesday morning, June 17th: Custom domain redirects incorrectly displaying warning page

“Custom domain users are reporting that traffic to their blog's Blogspot URL is inserting a redirect warning notifying users that they are leaving Blogger. Previously, no warning was issued and visits to the Blogspot URL were automatically re-routed to the user's Custom Domain.As of Saturday the service disruption is still unresolved.

Blogger engineers are aware of the issue and are working on a fix. We apologize for the issue, and will update this post when it is fixed.”

The author of Calculated Risk posted a poignant email from a long term reader in the Blogger help forum on Friday:

"Just wondering if everything is OK. Hope you are well. If you have decided to give it up, I wish you the best. You have been doing a Herculean job for the last few years, keeping an outstanding blog going. I don't have words to tell you how much I have appreciated you"At least this reader could be informed of the service disruption and directed to the new URL.

Book Review: The Greenspan Problem

by Calculated Risk on 6/20/2009 11:00:00 AM

CR Note: This is a guest post by Mathew Padilla of the Mortgage Insider blog. All opinions expressed are Matt's.

A book review by Mathew Padilla for Calculated Risk.

Count the following among the most accurate titles ever written: Nasdaq’s Peak was Greenspan’s. The title introduced a 2001 essay by James Grant, author of newsletter Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, in which the author addresses former Fed Chief Alan Greenspan’s approach to the ‘90s stock bubble: “He seeded it, accommodated it, celebrated it and defended it from those who believed they saw it turn into a bubble.”

The essay is an opening salvo against Greenspan to be followed by three other works that eviscerate the Maestro, the Federal Reserve and U.S. monetary policy in Grant’s late 2008 book Mr. Market Miscalculates: The Bubble Years and Beyond, which is a compilation of his essays celebrating the 25th anniversary of his newsletter. (I confess I submitted the review to Calculated Risk this month because I just finished reading the book.)

In the Nasdaq’s Peak essay Grant deconstructs Greenspan’s March 6, 2000 speech before the Boston College Conference on the New Economy. Greenspan praised the “revolution in information technology” including how managers formulated decisions with “real-time” information and that reduced uncertainty, allowing them to better control inventories. Grant delivers one of his many wry lines:

Thanks to clarity afforded by instantaneous communications, Cisco Systems had to write off only $2.25 billion in excess inventories during its third fiscal quarter, in addition to just $1.17 billion in restructuring and other special charges. … Lucent, Corning, Nortel and JDS Uniphase have been devastated by one of the greatest misallocations of investment capital outside the chronicles of the Soviet Gosplan. Who can conceive of the size of this waste had there been no e-mail?It’s the misallocation of capital that gets at the heart of Grant’s criticism of both Greenspan and the Fed. Grant saw Greenspan as the Chairman of Perpetual Intervention, juicing the money supply 1. When a big hedge fund had a serious hiccup 2 When computers might go bonkers over two-digit dates. 3. After Nasdaq tanked. But the former chief saw no need to raise rates to stem speculative excesses. (Recall the 2001 essay is before the most pernicious bubble of all.) Greenspan practiced a lopsided monetary policy.

Compounding his folly, Greenspan was slow to react to the Nasdaq crash and start lowering rates when boom turned to bust in the second half of 2000, Grant writes, adding: “(B)ecause information technology was an absolute and unqualified good thing, it followed that it could not be held responsible for a bad thing – for instance, the bottom falling out of capital investment and, therefore, out of the GDP growth rate.”

That was Grant annoyed. Grant disgusted comes across in a September 13, 2002 essay, Monetary Regime Change, in which Grant’s prose oozes with repugnance as he picks apart Greenspan’s speech that year at the “monetary jamboree” of the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank in Jackson Hole, Wyo. “Alan Greenspan washed his hands of responsibility for the bubble he said he could not have pricked even if he had noticed it floating above his desk on a string.” Again we are talking about the tech bubble – a warning that Greenspan was a deeply flawed policymaker. Grant goes on:

Following is a speculation on the outlines of a post-Greenspan monetary system. It is supported by some of the historical works that the chairman can read in the well-deserved retirement he should have taken starting in about 1996. We say “post-Greenspan” because, we believe, the Jackson Hole Speech will raise the odds against his reappointment (his current term expires in 2004), speed the day of his departure and reduce his policy-making influence for a long as he remains in office.Grant was right about Greenspan not being reappointed, but wrong about his waning influence. In his final years, Greenspan fueled a pernicious explosion in credit, and he provided intellectual cover to politicians either ideologically opposed to regulation or too preoccupied with other matters to get to it. The essayist also was prescient but a little early with this in 2002: “Only one of the troubles with bubbles is that, after they pop, ultra-low interest rates and extraordinary rates of credit expansion lose their stimulative potency. The rate of creation of new yen by the Bank of Japan stands at 26.1% year-over-year, but this outpouring has yielded no appreciable reflationary results.” Grant was exactly right, but after a property bubble, not a stock-market bubble.

Greenspan is the lighting rod, but monetary policy is the storm. Grant writes since the late 19th century to their creators, each monetary system suited the ages. “But none lasted much longer than a generation. The system in place since 1971 is the worldwide paper-dollar system.” Grant takes this idea and runs with it in Mission Creeps, a November 7, 2003 essay that takes stock of the Federal Reserve on the eve of its 90th anniversary. “The Federal Reserve would be unrecognizable to the men who conceived it.” The law creating the Fed defined its purposes as follows, “to provide for the establishment of the Federal Reserve banks, to furnish and elastic currency, to afford means of rediscounting commercial paper and to establish a more effective supervision of banking in the United States, and for other purposes.”

The founders, including Sen. Carter Glass (D.Va.), feared bank runs and their potential to disrupt commerce. They envisioned a central bank that could keep the banking system liquid. But they lived in the era of the gold standard, and never, ever dreamed of an expanding money supply designed to boost employment. Balancing full employment and appropriate inflation came later – the Fed and Congress found uses for the original act’s “and for other purposes.” Grant’s strongest ammunition is fired at the very idea of a central bank’s power to steer an economy, and all the myriad actors in it, by comparing economics to the hard science of physics in 2003:

Both use quantitative methods to build predictive models, but physics deals with matter; economics confronts human beings. And because matter doesn’t talk back or change its mind in the middle of a controlled experiment or buy high with the hope of selling even higher, economists can never match the predictive success of the scientists who wear lab coats. … Gov. Ben S. Bernanke is one of those true believers, as he reiterated last month in a lecture at the London School of Economic. “If all goes as planned,” said Bernanke, getting off on the wrong foot, “the changes in financial asset prices and returns induced by the actions of monetary policymakers lead to changes in economic behavior that the policy was trying to achieve.” If all went according to plan, the LSE would be teaching case studies in the triumphs of the Soviet economy.In yet another essay, There ought to be Deflation, in January 14, 2005, Grant builds on the idea of a monetary policy as a source of economic distortion. He quotes Friedrich von Hayek, who, while accepting the Nobel price for economics more than 20 years ago, said:

The continuous injection of additional amounts of money at points of the economic system where it creates a temporary demand which must cease when the increase of money stops or slows down, together with the expectation of a continuing rise in prices, draws labor and other resources into employment which can last only so long as the increase of the quantity of money continues at the same rate – or perhaps even only so long as it continues to accelerate at a given rate.And that is exactly what happened when Greenspan cut rates in the 2000s. Workers flooded into subprime lenders, construction companies, Home Depots, and on and on.

Grant bemoans, in more than one essay, the death of the gold standard. In his view a fixed currency would constrain both the Fed and the federal government. It might even have prevented a war of choice in Iraq, since what cannot be funded cannot be done. But fixed currencies have their disadvantages, writes another Nobel laureate, Paul Krugman, in another book tackling our current woes, his updated The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. A currency that is allowed to fall benefits an economy in recession since its exports become cheaper, Krugman argues. He’s also a proponent of a flexible currency giving a central bank freedom to expand money and combat unemployment.

Curiously, Krugman has a chapter in his book dubbed Greenspan’s Bubbles, but he does not address the Greenspan conundrum: what to do about the risk a Fed chairman will over stimulate asset prices while doing nothing to stop credit abuses. Until that problem is addressed I side with Grant and Hayek – expansionary monetary policy is dangerous.

In all of Mr. Market Miscalculates, I have but one quibble with Grant’s views. He cites the “socialization of risk” as encouraging reckless corporate behavior. The problem began with FDIC insurance and culminated in Greenspan’s interventions, including the orderly dissolution of hedge fund Long Term Capital Management. Grant’s case is that banks are more willing to lend to corporate cowboys if they think government will bail them out, or the market overall.

An alternative view is that FDIC insurance has been a key element among government initiatives that maintained safety and soundness in banking for some 50 years. It wasn’t until President Reagan initiated the anti-regulation era that insured institutions went bonkers – S&Ls binged on junk bonds and commercial real estate. Even now, with all that has happened, consumers are not lining up at insured banks in an all out panic – before FDIC insurance some good banks failed on mere rumors of trouble.

And moral hazard did not fuel the excesses of the era just ended. As an example, noninsured, nonbank New Century Financial secured more than $15 billion in credit lines from bigger banks in housing’s heyday. No one thought the subprime generator was too big to fail. And as soon as it wobbled, New Century found its credit cut off, and it fell into the abyss. This is the real issue with the modern era -- capital flows quickly, at times too quickly, into and out of any venture anywhere in the world.

On the whole, there is much genius in Grant’s observations. And his book covers more than what I touched on here. He gives a modern take on value investing, illuminates Wall Street’s mortgage fantasies, and more. As for a solution to the Greenspan problem, it is not Grant’s style to offer one. He never explicitly says the country should return to the gold standard or hack some appendages off the Federal Reserve. Grant is subtler, and more general. He simply warns us: change is coming.

Mathew Padilla is co-author of Chain of Blame: How Wall Street Caused the Mortgage and Credit Crisis, a USA Today Business Book of the Year, and hosts the Mortgage Insider blog.