by Calculated Risk on 5/11/2015 11:58:00 AM

Monday, May 11, 2015

More Employment Graphs: Duration of Unemployment, Unemployment by Education, Construction Employment and Diffusion Indexes

By request, a few more employment graphs ...

Here are the previous posts on the employment report:

• April Employment Report: 223,000 Jobs, 5.4% Unemployment Rate

• Employment Report Comments and Graphs

This graph shows the duration of unemployment as a percent of the civilian labor force. The graph shows the number of unemployed in four categories: less than 5 week, 6 to 14 weeks, 15 to 26 weeks, and 27 weeks or more.

This graph shows the duration of unemployment as a percent of the civilian labor force. The graph shows the number of unemployed in four categories: less than 5 week, 6 to 14 weeks, 15 to 26 weeks, and 27 weeks or more.The general trend is down for all categories, and the "less than 5 weeks", "6 to 14 weeks" and "15 to 26 weeks" are all close to normal levels.

The long term unemployed is less than 1.6% of the labor force - the lowest since November 2008 - however the number (and percent) of long term unemployed remains elevated.

This graph shows the unemployment rate by four levels of education (all groups are 25 years and older).

This graph shows the unemployment rate by four levels of education (all groups are 25 years and older).Unfortunately this data only goes back to 1992 and only includes one previous recession (the stock / tech bust in 2001). Clearly education matters with regards to the unemployment rate - and it appears all four groups are generally trending down.

Although education matters for the unemployment rate, it doesn't appear to matter as far as finding new employment.

Note: This says nothing about the quality of jobs - as an example, a college graduate working at minimum wage would be considered "employed".

This graph shows total construction employment as reported by the BLS (not just residential).

This graph shows total construction employment as reported by the BLS (not just residential).Since construction employment bottomed in January 2011, construction payrolls have increased by 951 thousand.

Construction employment is still far below the bubble peak - and below the level in the late '90s.

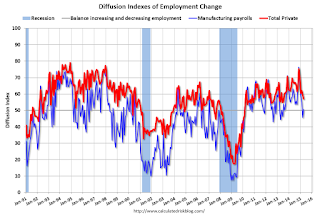

The BLS diffusion index for total private employment was at 57.0 in April, down from 59.5 in March.

The BLS diffusion index for total private employment was at 57.0 in April, down from 59.5 in March. For manufacturing, the diffusion index was at 50.6, up from 45.6 in March.

Think of this as a measure of how widespread job gains are across industries. The further from 50 (above or below), the more widespread the job losses or gains reported by the BLS. Above 60 is very good. From the BLS:

Figures are the percent of industries with employment increasing plus one-half of the industries with unchanged employment, where 50 percent indicates an equal balance between industries with increasing and decreasing employment.Overall private job growth was less widespread in April.

FNC: Residential Property Values increased 4.6% year-over-year in March

by Calculated Risk on 5/11/2015 09:31:00 AM

In addition to Case-Shiller, and CoreLogic, I'm also watching the FNC, Zillow and several other house price indexes.

FNC released their March 2015 index data today. FNC reported that their Residential Price Index™ (RPI) indicates that U.S. residential property values increased 0.9% from February to March (Composite 100 index, not seasonally adjusted).

The 10 city MSA increased 0.6% in March, and the 20-MSA and 30-MSA RPIs both increased by about 0.9% in March. These indexes are not seasonally adjusted (NSA), and are for non-distressed home sales (excluding foreclosure auction sales, REO sales, and short sales).

Notes: In addition to the composite indexes, FNC presents price indexes for 30 MSAs. FNC also provides seasonally adjusted data.

The year-over-year (YoY) change was slightly higher in March than in February, with the 100-MSA composite up 4.6% compared to March 2014. For FNC, the YoY increase had been slowing since peaking in March at 9.0%, but had held steady for the last few months.

The index is still down 18.6% from the peak in 2006 (not inflation adjusted).

This graph shows the year-over-year change based on the FNC index (four composites) through March 2015. The FNC indexes are hedonic price indexes using a blend of sold homes and real-time appraisals.

Most of the other indexes are also showing the year-over-year change mostly steady at around 5% for the last several months.

Note: The March Case-Shiller index will be released on Tuesday, May 26th.

Sunday, May 10, 2015

Sunday Night Futures

by Calculated Risk on 5/10/2015 08:28:00 PM

On Greece from the NY Times: I.M.F. and Central Bank Loom Large Over Greece’s Debt Talks

Greece is expected to repay 750 million euros, or $840 million, to the monetary fund on Tuesday as scheduled. For the rest of the year, however, its debt repayments to the fund and the central bank total nearly €12 billion.Monday:

...

Discussions in the Greek government have included assessing the pros and cons of not paying the central bank and the monetary fund ... a few of the debt specialists ... contend that they have a strong intellectual case for defaulting on debt owed to the central bank and the monetary fund. For too long, they assert, Greece has been stuck in a cycle of having to borrow more money to pay off maturing debts. And each time it borrows more, it must accept economic austerity measures that deflate its economy.

A result, they argue, is that five years after Greece’s first bailout, the nation’s economy has contracted by a quarter, and its debt burden is approaching 200 percent of its gross domestic product.

• At 10:00 AM ET, the Fed will release the monthly Labor Market Conditions Index (LMCI).

Weekend:

• Schedule for Week of May 10, 2015

• Lawler: Analyzing/Projecting Household Formations: It’s Not Just “Demographics”

From CNBC: Pre-Market Data and Bloomberg futures: currently S&P futures and DOW futures are mostly unchanged (fair value).

Oil prices were mixeed over the last week with WTI futures at $59.30 per barrel and Brent at $65.41 per barrel. A year ago, WTI was at $100, and Brent was at $108 - so, even with the recent increases, prices are down 40%+ year-over-year.

Below is a graph from Gasbuddy.com for nationwide gasoline prices. Nationally prices are up to $2.67 per gallon (down about $1.00 per gallon from a year ago).

If you click on "show crude oil prices", the graph displays oil prices for WTI, not Brent; gasoline prices in most of the U.S. are impacted more by Brent prices.

| Orange County Historical Gas Price Charts Provided by GasBuddy.com |

The Projected Improvement in Life Expectancy

by Calculated Risk on 5/10/2015 10:07:00 AM

Note: This is an update to a post I wrote some time ago with more recent data and projections.

Here is something different, but it is important when looking at demographics ...

The following data is from the CDC United States Life Tables, 2010 by Elizabeth Arias.

The most frequently used life table statistic is life expectancy (ex), which is the average number of years of life remaining for persons who have attained a given age (x). ... Life expectancy at birth (e0) for 2010 for the total population was 78.7 years. ... Another way of assessing the longevity of the period life table cohort is by determining the proportion that survives to specified ages. ... To illustrate, 57,188 persons out of the original 2010 hypothetical life table cohort of 100,000 (or 57.2 %) were alive at exact age 80.Instead of look at life expectancy, here is a graph of survivors out of 100,000 born alive, by age for three groups: those born in 1900-1902, born in 1949-1951 (baby boomers), and born in 2010.

emphasis added

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.There was a dramatic change between those born in 1900 (blue) and those born mid-century (orange). The risk of infant and early childhood deaths dropped sharply, and the risk of death in the prime working years also declined significantly.

The CDC is projecting further improvement for childhood and prime working age for those born in 2010, but they are also projecting that people will live longer.

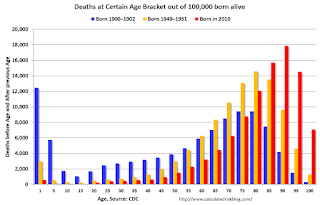

The second graph uses the same data but looks at the number of people who die before a certain age, but after the previous age. As an example, for those born in 1900 (blue), 12,448 of the 100,000 born alive died before age 1, and another 5,748 died between age 1 and age 5. That is 18.2% of those born in 1900 died before age 5.

The second graph uses the same data but looks at the number of people who die before a certain age, but after the previous age. As an example, for those born in 1900 (blue), 12,448 of the 100,000 born alive died before age 1, and another 5,748 died between age 1 and age 5. That is 18.2% of those born in 1900 died before age 5.In 1950, only 3.5% died before age 5. In 2010, it was 0.7%.

The peak age for deaths didn't change much for those born in 1900 and 1950 (between 76 and 80, but many more people born in 1950 will make it).

Now the CDC is projection the peak age for deaths - for those born in 2010 - will increase to 86 to 90!

Also the number of deaths for those younger than 20 will be very small (down to mostly accidents, guns, and drugs). Self-driving cars might reduce the accident components of young deaths.

In 1900, 25,2% died before age 20. And another 26.8% died before 55.

In 1950, 5.3% died before age 20. And another 18.7% died before 55. A dramatic decline in early deaths.

In 2010, 1.5% are projected to die before age 20. And only 9.7% before 55. A dramatic decline in prime working age deaths.

An amazing statistic: for those born in 1900, about 13 out of 100,000 made it to 100. For those born in 1950, 199 are projected to make to 100 - an significant increase. Now the CDC is projecting that 1,968 out of 100,000 born in 2010 will make it to 100. Stunning!

Some people look at this data and worry about supporting all the old people. To me, this is all great news - the vast majority of people can look forward to a long life - with fewer people dying in childhood or during their prime working years. Awesome!

Saturday, May 09, 2015

Lawler: Analyzing/Projecting Household Formations: It’s Not Just “Demographics”

by Calculated Risk on 5/09/2015 02:31:00 PM

From housing economist Tom Lawler: Analyzing/Projecting Household Formations: It’s Not Just “Demographics” (With a Special Focus on the 60’s and 70’s)

When talking about the outlook for housing, economists, analysts, and even home builders themselves often focus on “demographics.” Probably the most common discussion relates to recent trends in and future projections of the US population by age, with special emphasis on the age distribution of adults.

One of the simplest “models” used to analyze and project household growth is one that breaks out the actual and projected population by age buckets (or cohorts); looks at “recent” trends in “headship” rates, and then make what is often a “subjective” assumption of headship rates by age cohort based both on recent trends and historical “averages.”

There are, of course, several “challenges” related to this approach: first, of course, there are no timely reliable estimates of US households; rather, there are multiple and conflicting estimates based on different Census surveys. The only relatively reliable estimates come from the decennial Census, which is (1) seldom timely; and (2) provides analysts with only very infrequent “snapshots.”

The second challenge is that both headship and homeownership rates were decidedly unstable in the latter half of the last century, with many of the “swings” related not just to “economic” conditions but also to massive social and cultural changes.

Consider this simple example. Suppose that at the beginning of each decade one had perfect information on what the US population – both total and by age – would be a decade later, and suppose further that one assumed that “headship” rates (or the number of householders as a percent of the population) would be the same at the end of a decade as they were at the beginning of a decade for each age cohort. Here is what the resulting forecast for the increase in the number of households would have been compared to the “actual” increase in the number of households.

| Actual | Projected Assuming Previous Census Headship Rates | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960-1970 | 10,425,812 | 6,781,855 | 3,643,957 |

| 1970-1980 | 16,939,926 | 12,747,585 | 4,192,341 |

| 1980-1990 | 11,557,737 | 13,267,479 | -1,709,742 |

| 1990-2000 | 13,532,691 | 14,292,026 | -759,335 |

| 2000-2010 | 11,236,191 | 13,546,146 | -2,309,955 |

As the table indicates, a “constant for a decade headship-rate” model for household growth produced household projections that were massively to low during the 60’s and 70’s, but were significantly too high over the subsequent 30 years.

As I hope most folks know, the 60’s and 70’s were a time of huge social and cultural upheaval and change, and I won’t discuss these. One result, however, was a massive surge in the number of people living alone – from 1960 to 1980 the number of people living alone increased to 18.2 million from 7.1 million. The 158% jump in the number on one-person households from 1960 to 1980 obviously vastly exceeded the 26.3% increase in the overall population, and the share of people living alone increased for each “adult” age group – with especially large increases in “young” adults living alone. This “explosion” in the number of people living alone reflected substantial declines in marriage rates, sizable increases in the divorce rate (from 1970 to 1980 the number of divorced people living alone double), and significant increases in the number of widows living alone. It did not, interestingly, reflect a decline in the number of young adults living at home. Rather, it reflected a surge in the number of young adults who left home to live alone.

| Share of Population Living Alone by Age Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1980 | 1970 | 1960 |

| 15-64 | 7.4% | 4.9% | 3.9% |

| 15-24 | 4.0% | 1.7% | |

| 25-34 | 9.0% | 3.8% | |

| 35-44 | 5.9% | 3.3% | |

| 45-64 | 10.3% | 9.3% | |

| 65+ | 27.7% | 24.6% | 17.5% |

The surge in the number of people living alone, which was driven as much by and probably more so by social and cultural changes as opposed to “economic” changes, produced sized increases in “headship” rates (and big declines in average household sizes), and as a result household growth massively outpaced population growth in a fashion not readily explainable by “demographics.”

Given the surge in the number of people living along, especially among “younger adults,” from 1970 to 1980, one might have expected the overall US homeownership rate to have declined over this period (the homeownership rate for one-person households has traditionally been way below that for married-couple families). In fact, however, the overall homeownership rate increased, mainly reflecting sizable increases in the homeownership rates for married-couple families in all age groups.

| Homeowership Rates | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1970 | ||

| Total | 64.4% | 62.9% | |

| Married Couple Households | 77.8% | 70.7% | |

| 15-24 | 36.5% | 26.0% | |

| 25-34 | 66.9% | 56.9% | |

| 35-44 | 82.6% | 76.7% | |

| 45-64 | 87.1% | 80.8% | |

| 65+ | 83.0% | 78.4% | |

| Other 2+ Households | 43.8% | 49.5% | |

| One-Person Households | 43.5% | 42.4% | |

During most of the 1970’s the “typical” home buyer purchased a home that was much more modest than was the case in subsequent decades, both in terms of size, price relative to income, and housing expense relative to income, as during most of the decade buyers typically purchased a home mainly as a place to live rather than as an investment. In addition, manufactured housing was a much more important source of “affordable” housing back then – in 1980 16% of owner-occupied housing units built between 1970 and 1980 were manufactured homes/trailers.

As inflation accelerated during the decade, however, an increasing number of buyers, looking for a “hedge” against inflation, began to focus more on housing as an investment as well. That trend, which was temporarily halted by the surge in interest rates and the exceptionally severe recession of the early 1980’s, accelerated in the latter half of the 1980’s for a variety of reasons, and continued to accelerate (with a brief recession-related respite in the early 90’s) through much of last decade.

But that discussion will be in a subsequent edition.